12 Poverty and malnutrition of children in Maroua

Robert Nanche Billa and Maidjonle Muruele Brillant

Abstract

Malnutrition is usually associated with poverty and food insecurity. The vast majority of hungry people live in underdeveloped regions. The objective of this work is to examine the causes and consequences of malnutrition of children between 6-59 months in Maroua in the Far North Region of Cameroon, which has a poverty rate of 74.3%. Thirty key informants including health district heads and health workers were interviewed and 150 questionnaires were administered to mothers of malnourished infants. The following results were obtained: As mothers’ level of education increases, the number of mothers who regularly give fruit to their children also increases. Equally, as the mother’s age at marriage increases, the healthier her children are. Malnourished children have limited interactions with other children and their parents spend a lot of money on hospital bills and their education because of their limited intellectual capacities.

Keywords: malnutrition, children, poverty, education, food

Résumé

La malnutrition est généralement associée à la pauvreté et à l’insécurité alimentaire et une grande majorité des personnes souffrant de la faim vivent dans les régions en développement. L’objectif de ce travail est d’examiner les causes et les conséquences de la malnutrition des enfants de 6 à 59 mois à Maroua dans la région de l’Extrême-Nord qui a un taux de pauvreté de 74,3%. Trente informateurs clés : chefs de district sanitaire, agents de santé ont été interviewés et 150 questionnaires ont été administrés aux mères de nourrissons malnutris. Les résultats suivants ont été obtenus : Au fur et à mesure que le niveau d’éducation des mères augmente, le nombre de mères qui donnent régulièrement des fruits à leurs enfants augmente également. De même, plus l’âge du mariage de la mère augmente, plus les enfants ne sont en bonne santé. Les enfants malnutris ont des interactions limitées avec les autres enfants et leurs parents dépensent beaucoup d’argent pour les factures d’hôpital et leur éducation en raison de leurs capacités intellectuelles limitées.

Mots clés : malnutrition, enfants, pauvreté, éducation, alimentation

Introduction

Poverty is much more than income inequality; it encompasses health, social, and gender inequalities. It refers to all the different conditions of life: lack of access to basic needs, resources, and services as well as lack of income and inequalities (Helene, 2008). Poor health and low survival rates among African children are closely linked to lack of proper access to healthcare, which is a function of poverty. (Kempe, 2007). Poverty alleviation will be held back and frustrated without addressing the problems of hunger and undernourishment. Sub-Saharan Africa has the highest proportion of people living in poverty, with nearly half of the population living below the international poverty level. They suffer from hunger, malnutrition, nutrition transition, obesity and non-communicable diseases, thereby creating inequalities that need to be addressed politically (Tola, Parvin, Oyediran, Rekia and Liuis, 2009)

The poverty rate (or incidence of poverty) in the Far North region of Cameroon in 2014 was 74.3%, nearly double of the national level. It is higher in households headed by women (81.2%) than in those headed by men (22.9%). Poverty rises with the size of the household, increasing from almost 28% in one-person per household to 86% in households with at least 8 persons. It also seems to increase with the age of the head of household: 60.4% in households headed by a person under 35, 76.9% in households headed by someone who is about 35 to 64 years old and 83.2% in households headed by a person who is 65 and above (INS, 2019). However, the question we ask in this work is: what is the impact of poverty on the feeding habits of children of about 6-59 months in Maroua?

Poverty has been reported as the principal cause of hunger, and the vast majority of hungry people live in developing regions (Adeyeye, Omowonuola and Tiamiyu, 2017). Children, pregnant women, and the elderly are the victims of malnutrition. Poor nutrition causes at least half of the 10.9 million child deaths each year in Africa (FAO, 2013; WHO, 2013). About 800 million people globally are undernourished, of which 780 million reside in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. In 2015, inadequate food intake and poor dietary quality were responsible for ill-health and in 2017, 11 million deaths and 255 million disability-adjusted life years were attributable to dietary risk factors (Afshin, Fay, Cornaby, Ferrara, and Salam, 2017). Children under the age of 5 years are highly vulnerable to malnutrition: in 2019, globally 144 million such children were stunted (short for his/her age), 47 million wasted (thin for his/her height) and 38 million overweight (abnormal or excess bodyweight) (UNICEF, WHO, WBG, 2020).

The other question we ask in this work is: what are the consequences of malnutrition on children who are about 6-59 months in Maroua?

Malnutrition is linked to a deficiency, excess, or imbalance of energy and other macro and micro-nutrients. It consists of differing levels of under- or over- nutrition, which leads to changes in body composition, body function, and clinical outcomes. In other words, malnutrition is an all-inclusive term that represents all manifestations of poor nutrition and ranges from extreme hunger and under nutrition to obesity (Faareha, Rehana, Salam, Lassi, and Jai, 2020).Malnutrition is usually associated with poverty and food insecurity, and malnourished is defined as poorly or wrongly fed and having a poor or inadequate diet (MSN Encarta dictionary, 2021). Many of the diets of poor people have adequate kilocalories to meet or exceed their energy requirements, but lack the dietary quality needed to promote optimal health and prevent chronic disease. Hunger is a potential, although not a necessary, consequence of food insecurity (National Research Council, 2006). When hunger is recurrent, it results in under-nutrition. Socially, hungry people are individuals who occasionally obtain an inadequate quantity or quality of food and nourishment, and hunger can be present even when no clinical symptoms or health problems associated with food deprivation exist (National Research Council, 2006).

Globally, nearly 195 million children younger than five years are undernourished. Malnutrition is most obvious in the developing countries, where the condition often takes severe forms; images of emaciated bodies in famine-struck or war-torn regions (Brown and Pollitt, 1996). Although severe underfeeding in infancy can certainly lead to irreparable cognitive deficits, it cannot fully account for intellectual impairment stemming from more moderate malnutrition because factors such as income, education and other aspects of the environment can apparently protect children against the harmful effects of a poor diet or can exacerbate malnutrition (Brown and Pollitt, 1996). The objective of this work is to explain the causes and consequences of malnutrition among infants of about 6-59 months in the town of Maroua.

The explanatory sequential mixed method design was used to carry this research. Quantitative data were collected and analyzed first and the results were used to plan the qualitative investigations, that is, to construct themes that were discussed during interviews. Quantitative results are presented as pie charts and histograms. Qualitative data are analyzed using narrative and thematic analysis techniques.

We used the purposive sampling technique which involves the identification and selection of individuals or groups of individuals that are proficient and well-informed with the malnutrition of children in Maroua. Surveys were carried on a sample of 150 mothers of malnourished infants aged from 6-59 months who have had access to a feeding program offered by a non-governmental organization. We conducted interview with 30 key informants who were health district heads, health workers, and NGO personnel in charge of feeding program.

Presentation of Results and Analyses

This section first of all examines children’s feeding habits and then the causes and consequences of children’s malnutrition.

Children’s feeding habits

The quantitative and qualitative feeding habits of children are assessed by considering the number of times they eat per day as well as their consumption of vegetables and fruit.

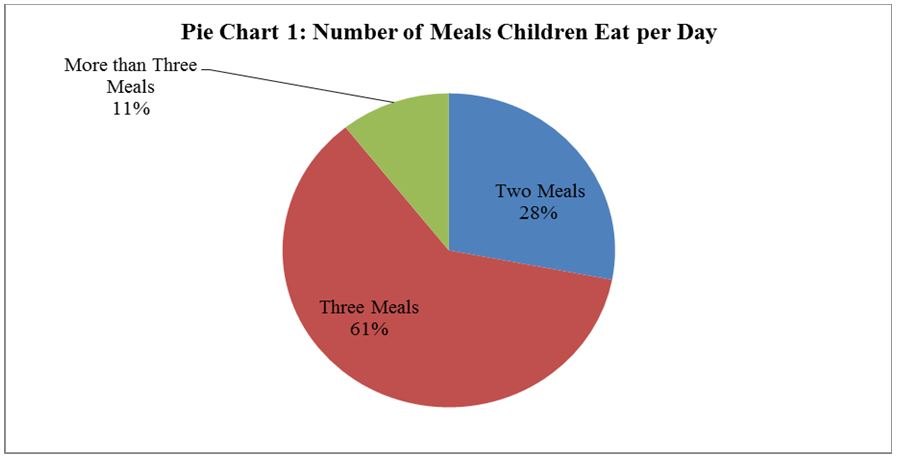

Pie chart 1 indicates that only about 61.3% and 10.7% of children in Maroua eat three meals and more than three meals per day respectively. Therefore, about 72% of the children in Maroua eat about three meals and above and about 28% of them do not have access to three meals per day.

This corroborates key informants’ ideas that poverty does not enable some families to have enough food because they lack the means to buy food. Most of the mothers are just housewives with no earnings, or they do petty trading by selling peanuts, salt, or refined oil. Below we examine whether their dietary intake is qualitative.

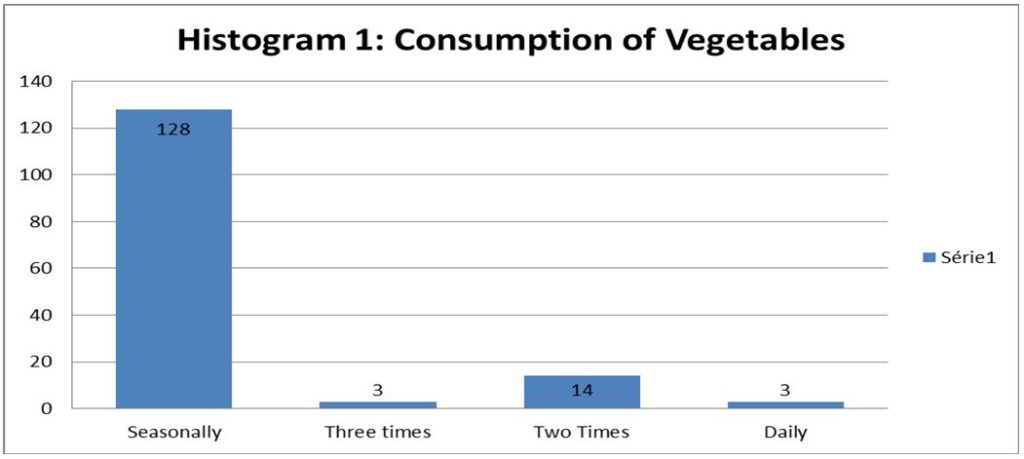

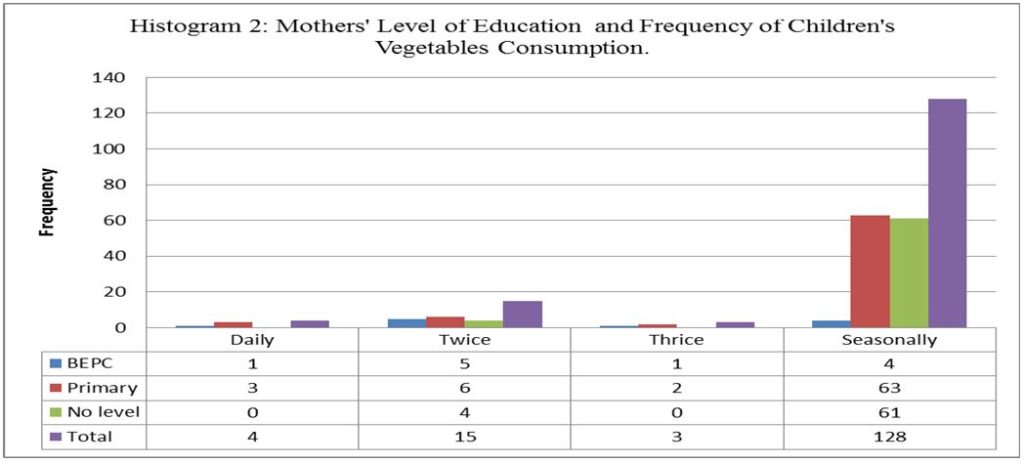

Histogram 1 indicates that children in the city of Maroua are seriously malnourished qualitatively. Although 72% of them eat three and more times per day, only 2.7% of them consume enough vegetables daily. About 85.3% of them consume enough vegetables seasonally while 2% and 10% consume vegetables thrice and twice a week respectively.

Our results show that 88.28% of children who seasonally consume vegetables, regularly fall sick while 50%, 93.33% and 75% of those who consume them three times, two times and daily respectively regularly fall sick too. There is a slight correlation between the consumption of vegetables and regularly falling sick. The percentage of children of the latter group who regularly fall sick is slightly lower than the former. Therefore, the regular consumption of vegetables has a minor impact on the health of children. It is worth noting that about 88% of the children are regularly sick and only about 11.33% of them rarely fall sick. It is quite surprising that about 82.15% of those who rarely fall sick consume vegetables seasonally.

Most of our informants said they do not have enough money to buy vegetables and fruit for the entire family. So, they cannot give food to one child while “the others are just watching him or her eating.” Aissatou, a mother of a malnourished child, said: “We eat vegetables seasonally only because during harvest they are cheaper, so we can get them for the entire house.” Therefore, mothers do not give enough vegetables to their children because they do not have enough money to buy them for the entire family. Consequently, they prefer eating those vegetables seasonally because during harvesting periods, they are cheaper and the entire family can eat.

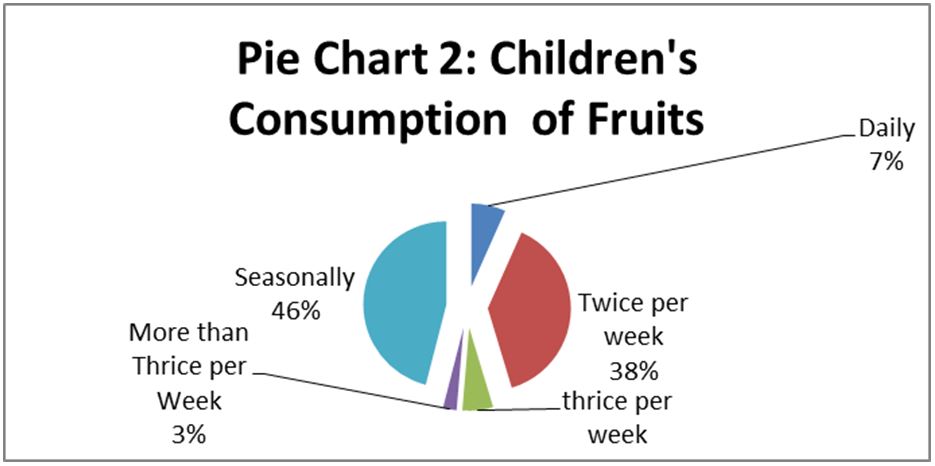

Pie chart 2 indicates that about 6.7%, 38.7%, 6%, 2.7%, 46% of children consume enough fruit daily, twice a week, thrice a week, more than thrice a week and seasonally respectively. Therefore, about 46% of them do not consume fruit in a week. Our results show that 88% of them too, regularly fall sick and 80%, 93.13%, 88.88%, 75% and 85.50% of those who consume fruit daily, twice a week, thrice per week, more than thrice per week and seasonally, regularly fall sick. The above shows that children falling sick regularly is not due to the non-consumption of fruit because the number of children who consume fruit daily still fall sick as regularly as those who do not consume fruit daily.

Children at that stage need nutrients for the development of their brains and intellectual faculties. Brown and Pollitt (1996) assert that children who consume nutritious food scored significantly higher at school than those who eat less nutritious food. Equally, lack of money to provide them with a balanced diet affects their normal growth both physically and mentally. Thus, poverty is one of the contributing factors to child malnutrition in Maroua. Peña and Bacallao (2002) confirm that people living in poverty often face financial limitations which hinder their ability to access safe, sufficient, and nutritious food. Equally, Banerjee and Duflo (2011) state that food insecurity compromises people’s ability to acquire the amount of food needed to fulfill the bodily requirement of calories and that, without sufficient calorie intake, an individual may not be able to build up energy or strength to carry out everyday life activities. It also hampers earning capacity.

Factors such as health, nutrition and formal education are components of human capital which benefit individuals later in life (Dao, 2008). The process of developing human capital begins early in infancy and continues throughout the life of the individual (Institute for Fiscal Studies, 2006). Because this process is incremental in nature, early choices, inputs and events will have the power to either debilitate or facilitate development at more advanced stages (Rasmus, 2009).

Causes of Children’s Malnourishment

Mothers’ Level of Education

In this section we examine whether the malnourishment of children was due to the level of education of their mothers.

Our results show that mothers’ levels of education influence their children’s consumption of vegetables. About 9.09%, 4.05% and 0% of mothers with B.EP.C., primary level and no education respectively give vegetables to their children daily. Mothers who have the B.E.P.C. give more vegetables to their children daily than those who ended at the primary level while those with no education give few vegetables to their children daily. INS (2019) states that the level of poverty decreases as the level of education of the head of household increases: from 81% in households where the head has no schooling to 33% in those where the head has a higher educational level. Equally, our results show that the children of mothers with no education suffer from malnutrition the most.

About 45.45%, 8.11% and 6.15% of mothers with the Brevet d’Etudes du Premier Cycle (B.E.P.C), First School Leaving Certificate (F.S.L.C). and those with no education give their children enough vegetables twice a week. It is noticeable that more mothers with the B.E.P.C give vegetables to their children twice as often as those with F.S.L.C and those with no education.

About 36.36%, 85.14%, 93.85% of those with the B.E.P.C, F.S.L.C. and those with no education give their children vegetables seasonally. This shows that illiterate mothers give their children fruit only seasonally. As level of education increases, the number of mothers who give their children fruits seasonally reduces. Therefore, the mother’s level of education is an important factor in explaining children’s malnutrition in Maroua. There is a correlation between mothers’ level of education and children’s consumption of vegetables, and this implies that lack of education has a great influence on feeding habits.

The above corroborates the view of Helene (2008) which states that women’s education is empowering, and it brings major improvements in maternal and child nutrition. Equally, women’s empowerment is one of the most effective ways of cutting down birth rates. Maternal malnutrition is linked to excess maternal and neonatal mortality. Therefore, improvements in women’s nutrition will decrease mortality and raise the nutritional status of surviving children. In addition, improved maternal nutrition will contribute positively to women’s economic productivity and a decrease in the chronic disease risk associated with poor nutrition in early life.

Mothers with little or no education are unaware of the importance of a balanced diet and how to cook for their children. Mrs Haoua, a nutritionist at the CSI of Bamare, said: “Mothers coming here with malnourished children do not understand that not feeding vegetables to their children harms them. Mothers think that a balanced diet is reserved for the rich because the poor do not have the money needed to regularly buy fruit, vegetables, and proteins for their children.”

What they don’t realize is that ‘‘with 300 frs CFA, we can cook a balanced meal for a child,” said Mrs Patale, focal point nutrition at the CSI of Douggoi. Concerning alimentary restrictions, mothers of infants of less than a year prefer not to give certain nutrients which are necessary for the well-being and normal growth of their children because they think they will make the child fall sick: ‘‘Elles ne mettent pas l’arachide et le sucre dans la bouteille des enfants[1]’’ because they think the child will catch ‘‘targassiré’’.

Only 33.3% of these mothers sometimes wash fruit and vegetables before consumption, which means that 66.66% consume unhygienic fruit, which cause children to fall sick. In addition, the children grow up in dirty environments that affect their well-being. Mothers do not cover children’s food, leaving it exposed to flies and bacteria. There is also a bad feeding practice in which special care is not given to infants as they eat the same food with their elders. Mothers said all their children were treated equally without any distinction.

About 87% of women give their children water when they are less than six months old. Some even give their children water right from their birth. They violate the principle of RBF[2] that medical doctors prescribe to them at the hospital. Since 78% of the women drink water from wells and 62% never treat water before drinking it, it is highly probable that children drink contaminated water full of pathogens, thereby exposing them to waterborne diseases. Besides, waterborne diseases render children more vulnerable to malnutrition.

The poor spacing of children or family planning is also a cause of malnutrition. About 43% of mothers applied one year of interval in between their children. Slightly linked to the above is the fact that mothers of malnourished children stay at home with their children, administering to them medications given to them by traditional doctors. Madam Aissatou Bouba, nutrition focal point at the CSI of Bamare, said that “they only take their children to the hospital when they are already weak, reducing their chances of recovery.”

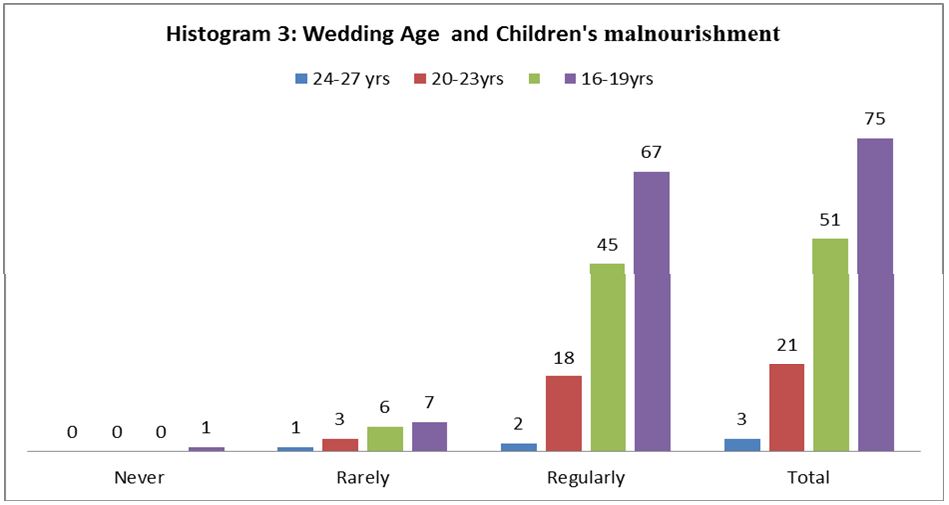

Our research show that 33.33%, 14.29%, 11.74%, and 9.33% of the children whose mothers got married when they were 24-27 years, 20-23 years, 16-19 years and 12-15 years respectively have children who rarely fall sick. The figures indicate that mothers who got married when they were older have children who rarely fall sick. Therefore, as the marriage age of mothers increases, the more likely their children will rarely fall sick and vice versa. Inversely, 66.67%, 85.71%, 88.23%, 89.33% of mothers who were between 24-27 years, 20-23 years, 16-19 years and 12-15 years respectively when they got married have children who regularly fall sick. This also indicates that the younger a woman is when she gets married the more likely her children will fall sick. About 88% of the children fall sick, although marriage age plays an important role in the frequency of children falling sick. Therefore, even if marriage age is changed, the impact of the regularity of children’s sickness will still be felt.

Girls who marry very young with little knowledge about looking after a child cannot take good care of a child. At 15 years old, a girl does not know much about parenting. Half of the mothers in our sample got married before their 16th birthday because a majority of those who live in the city of Maroua are Fulani, who send their children to early marriages. Added to mothers’ high rate of illiteracy, early marriages make matters worse for children in Maroua.

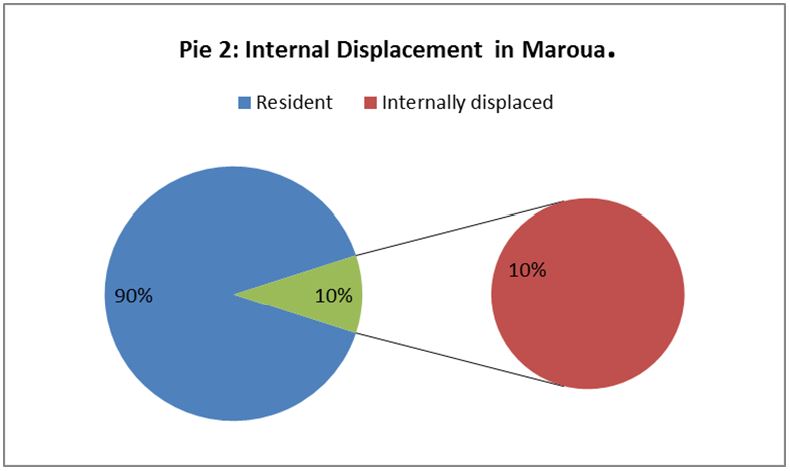

Internal Displacement and children’s malnutrition

There are many refugees and internally displaced persons in Maroua who fled from the Boko Haram terrorist activities that started in 2014. This displacement is also responsible for the malnutrition of children, though at a lower rate. Had those children not been displaced from their homes to an unknown land, they wouldn’t have been malnourished. But even the host community also feels the effects of this crisis due to the rising prices of the available foods in the various markets.

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (2016) states that the threat of death and serious injury resulting from conflict can result in such a desperate situation that people abandon their homes, leaving nearly everything behind: house, land, sources of income, and most possessions, thereby exacerbating their poverty-line and jeopardizing the well-being of their children.

Consequences of Child Malnutrition in the City of Maroua

Children suffering from malnutrition have retarded growth, a process known as marasmus, a type of protein-energy malnutrition that mainly affects children. It results from a severe deficiency of calories, proteins, carbohydrates, vitamins, and minerals. Malnourished children are underweight for their ages due to wasting. Therefore, malnutrition affects the normal physical growth of children and consequently their health status. This is alarming in Maroua because 88% of the children are regularly sick. Most often, a two-year-old child who has been physically and intellectually retarded will look more like a newborn baby because of lack of nutrients. Mr. Ndouwe, the regional nutrition focal point, said: “experience has proven that such children grow up with limited intelligence and can hardly get good results in school.’’ This means that malnourished children of today have limited intellectual capacities.

Brown and Pollitt (1996) state that under-nutrition triggers an array of health problems in children, many of which can become chronic. It can lead to extreme weight loss, stunted growth, weakened resistance to infection and, in the worst cases, early death. The effects can be particularly devastating in the early years of life when the body is growing rapidly and needs for calories and nutrients are high.

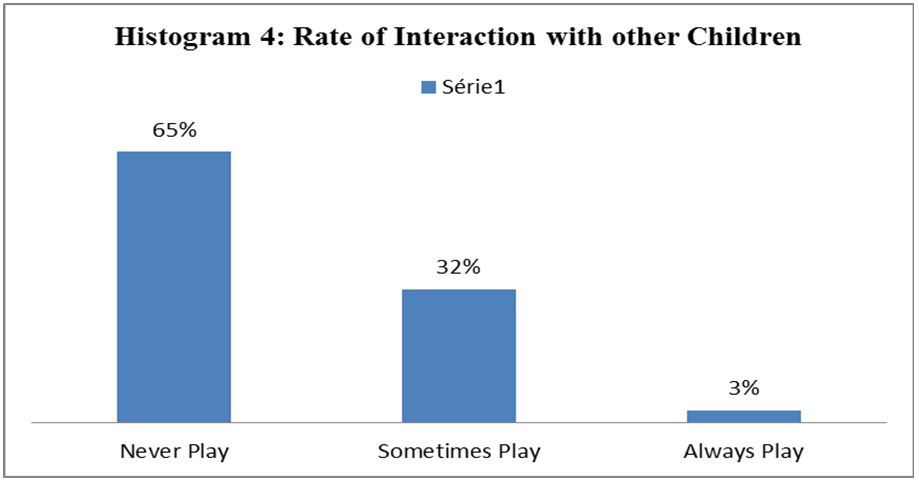

Low Rate of interaction with Children

The above bar chart shows that 65% of malnourished children never play with other children while just 32% sometimes play with their peers. Therefore, malnourishment has a negative impact of the well-being or development of children because they are likely not to have interactions or play with other children. They are always sick and weak and do not have the strength to play, so they sleep all day long. Brown and Pollitt (1996) explain that cognitive disability in undernourished children might stem from reduced interaction with other people and with their surroundings

Social and Economic Burdens

A key informant told us ‘‘the parent of a malnourished child spends a lot of money as she has to pay for hospital bills and buy food for the recovery of the child.’’ Parents of such children do not only spend money but also their energy and time in taking care of them. Mr. Ndouwe observed that the parents of malnourished children who repeat a class several times due to intellectual development deficiency pay more school fees and books yearly. Our informants affirm that malnourished children are a burden on their parents and perpetuate their poverty cycle and the economic stagnation of their community when their parents fail to contribute to the development of their local communities.

Informants agree that malnutrition might be the cause of social ills like robbery and other forms of juvenile delinquency. Malnourished children, because of their weak intellectual capacities, fail at school, thereby making it difficult for them to make a living.

Conclusion

It was found that only about 61.3% and 10.7% of children in Maroua eat three meals and more per day respectively. Therefore, about 72% of the children in Maroua eat about three meals and above and about 28% of them do not have access to three meals per day. Equally, children in the city of Maroua are malnourished qualitatively. Although 72% of them eat three and more times per day, only 2.7% of them consume enough vegetables daily. The regular consumption of vegetables has a slight impact on the health of children. It is worth noting that about 88% of the children are regularly sick and only about 11.33% of them rarely fall sick. It is quite surprising that about 82.15% of those who rarely fall sick consume vegetables seasonally.

The regular ill-health of children is not due to the non-consumption of fruit because the number of children who consume fruit daily still regularly fall sick as high as those who do not consume fruit daily. As their level of education increases, the number of mothers who give their children fruit seasonally reduces. Mothers’ level of education is an important factor in explaining malnutrition of children in Maroua. About 88% of children fall sick, although the age at marriage of the mother plays an important role in the frequency of children falling sick. Therefore, even if the marriage age is changed, the impact of the regularity of children’s sickness will still be felt.

Empowering women will bring major improvements in maternal and children’s nutrition because it is one of the most effective ways of cutting down birth rates. Improvements in women’s nutrition will decrease mortality and raise the nutritional status of surviving children.

References

Adeyeye, S., Omowonuola, A. and Tiamiyu , H. (2017). Poverty and malnutrition in Africa: a conceptual analysis, Nutrition & Food Science, Emerald Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/NFS-02-2017-0027

Afshin, A. Fay, K., Cornaby, Ferrara, G. and Salama, J. (2019). Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 393(19), 58-72.

Banerjee, A. and Duflo, E. (2011). More than 1 billion people are hungry in the world. Foreign Policy, 20, 66-72.

Brown, L. and Politt, E. (1996). Malnutrition, poverty, and intecllectual Development. National Library of Medicine, 274(2), 38-43.

Dao, M. (2008). Human Capital, Poverty, and Income Distribution in Developing Countries. Journal of Economic Studies, 35(4), 294-303.

De Onis, M., Frongillo, E. and Blo, M. (2000). Is Malnutrition Declining? An Analysis of Changes in Levels of Child Malnutrition since 1980. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 78(10), 1222-1233.

Faareha, S., Rehana, A., Salam1, Z., Lassi and Jai, K. (2020). The Intertwined Relationship Between Malnutrition and Poverty. Frontier in Public Health Review, 8(3), 1-5.

F.A.O. (2013) Women, Men and Nutrition. http://www.fao.org/gender

Institute for Fiscal Studies, 2006, Human development and poverty reduction in developing countries. https://gtr.ukri.org/project/7335760A-FEE5-4283-B982-12AF3F2774C8#/tabOverview

INS, (2019). Enquête Complémentaire à la Quatrième Enquête Camerounaise Auprès des Ménages (EC-ECAM 4).

Larry, B. E., (1996). Pollitt Malnutrition, Poverty and Intellectual Development Scientific American Inc.

Helene, F. (2008). Poverty. The Double Burden of Malnutrition in Mothers and the Intergenerational Impact. New York Academy of Sciences 1136, 172-184.

Kempe, R. (2007). Child Survival, Poverty, and Labor In Africa. Journal of Children and Poverty, 11(1), 19-42.

National Research Council, (2006). Food Insecurity and Hunger in the United States: An Assessment of the Measure. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Peña, M. and Bacallao, J. (2002). Malnutrition and poverty. Annual Review of Nutrition, 22, 241-253.

Rasmus, H. (2009). Malnutrition, Poverty,and Economic Growth Health Economics Health Econ. Wiley Inter-Science, 18, 77-88.

Tola, A., Parvin, M., Oyediran, E., Rekia, B. and Lluís, S. (2009). Breaking the poverty/malnutrition cycle in Africa and the Middle East Nutrition Reviews, 67, 540-546.