1 Forced migrants navigating the Boko Haram crisis – Continuity and rupture

Bjørn Arntsen

Abstract

The Boko Haram crisis has forced people in the border areas between northeastern Nigeria and Cameroon to migrate, and since 2014 many have ended up living in neighbourhoods of Maroua, the capital of Cameroon’s northernmost region. A video-based fieldwork among forced migrants in the Doursoungo district, encounters with forced migrants and hosts in other districts, and with NGO workers, serve as the basis for this paper. It addresses how the forced migrants attempt to achieve social security and access economic opportunities. Continuities exist in the ways the forced migrants make use of previously established networks – business, family, friends, ethnicity, religion – but discontinuities are also evident. Forced migrants are under pressure, as families have been dispersed, have lost their main providers and their previous livelihoods. Some have managed to establish a new and solid economic basis for themselves and their dependents. Others struggle to make ends meet. The forced mobility has concrete links to the past, while continuous repurposing takes place. Personal histories, relational networks and current circumstances are intertwined and have been decisive for the forced migrants’ abilities to create a new livelihood for themselves, to deal with the established systems of humanitarian aid, and the locals of their host communities.

Key words: Forced migration, video-based fieldwork, personal histories, networks, repurposing

Résumé

Les crises de Boko Haram ont contraint les habitants de la zone frontalière entre le nord-est du Nigeria et le Cameroun à se déplacer, et nombre d’entre eux se sont retrouvés depuis 2014 dans les quartiers de Maroua, la capitale de la Région de l’Extrême-Nord du Cameroun. Basé sur un travail de terrain dans le quartier de Doursoungo, des rencontres avec des migrants forcés et des hôtes dans d’autres quartiers et avec des ONG, l’article focalise sur comment les migrants forcés tentent de réaliser la sécurité sociale et économique. Des continuités existent dans la manière dont les migrants forcés utilisent les réseaux préalablement établis – affaires, parents, amis, origine ethnique, religion -, mais des ruptures sont également évidentes. Les migrants forcés sont sous pression, car les familles ont été dispersées, ont perdu leurs principaux pourvoyeurs et leurs anciens moyens de subsistance. Certains ont réussi à établir une base économique nouvelle et solide pour eux-mêmes et leurs personnes à charge. D’autres ont du mal à joindre les deux bouts. La mobilité forcée a des liens concrets avec le passé, tandis qu’une réorientation continue d’avoir à lieu. Les histoires personnelles, les réseaux relationnels et les circonstances actuelles sont étroitement liés et ont été décisifs pour que les capacités des migrants forcés créent un nouveau moyen de subsistance pour eux-mêmes, pour faire face aux systèmes d’aide humanitaire établis et aux habitants de leurs communautés d’accueil.

Mots clés : migration forcée, travail de terrain basé sur la vidéo, histoires personnelles, réseaux, réorientation

Introduction

The humanitarian crisis of the Lake Chad Basin, caused by the extreme violence related to the Boko Haram insurgency, is well documented by the media. Many stories of sad outcomes could be told as tens of thousands have lost their lives and millions have been forced to leave their homes. The historical stages of the insurgency (Mohammed, 2014) and the multiple causes behind its appearance have been much discussed. Like poverty and mismanagement of this region by administrative authorities, the generation of adolescents who have been educated in Koranic schools that are unrecognized in the national education systems, have lost hopes of a decent future and become victims of the Wahhabist/Salafist influences. (Magrin & Pérouse de Montclos, 2018)

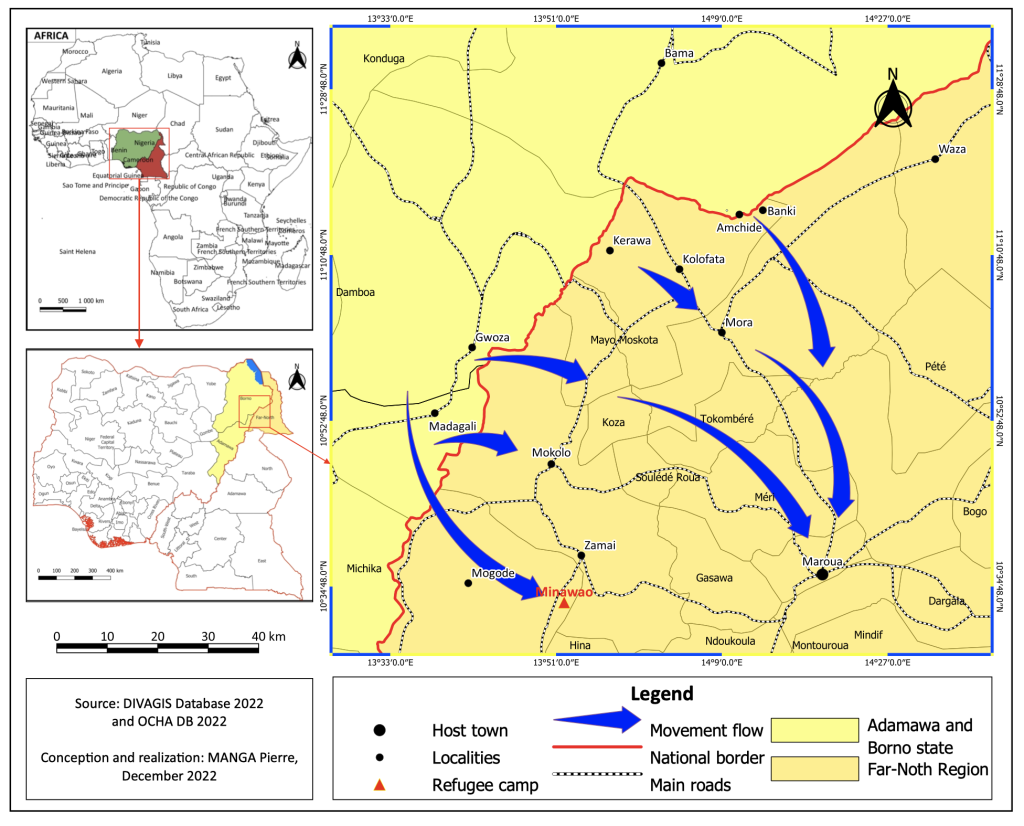

Maroua, the capital city of the far north region of Cameroon, has during the last six years received numerous forced migrants from the border areas with northeastern Nigeria . My aim in this paper is to show how the forced migrants navigate the complex and challenging conditions with which they are faced. Continuities exist in the ways they have made use of previously established networks. However, their lives are also marked by discontinuities. Families have lost their main providers, have been dispersed and lost their previous livelihoods.

A video-based fieldwork with a family of forced migrants from the border area living in the neighborhood of Doursoungo in Maroua, interviews/conversations with migrants in other districts[1], encounters with locals of the host districts and NGO workers, visits to the refugee/IDP camps in the Mandara Mountains, form the basis of this paper that addresses how the migrants attempt to attempt to achieve social security and access economic opportunities. How have the interrelatedness of personal histories, relational networks and current circumstances been decisive for the migrants’ abilities to fend for themselves, to deal with the established emergency relief systems, with the locals of the host communities and an eventual return to their home communities?

The story of Alhaji Oumar, Fatimatou and Lami

Alhaji Oumar and his two wives, Lami and Fatimatou, lived in the Nigerian border town of Banki where Alhadji Oumar was trading motorcycles and gasoline from Nigeria to Cameroon. The family had a good standard of living with shops at both sides of the border. When the border was closed in 2012 by Nigerian authorities, the family moved all their activities to the Cameroonian side. Their escape from Cameroonian Banki in 2014 was far less controlled. Cameroon then declared war on Boko Haram and attacks by Boko Haram also took place on the Cameroonian side. The family had to flee with almost none of their belongings with them. In Maroua they were offered the chance to stay in the house of Alhaji Kaka, a Kanuri from Am Chide who had established himself in Doursoungo at the end of the 1990s. Savings from previous business activities at the border meant the family were able to rent the flat they are still living in at the other side of the crossroads of Alhaji Kaka’s house.

The business was gone, and the family were flat broke. After some time, Alhaji Oumar was able to revitalize a trade in mattresses from Nigeria to Maroua, that his brother had left behind. His brother was suspected of Boko Haram complicity and imprisoned in Banki in 2015 by Cameroonian authorities, and had not been seen since. Alhaji Oumar is running this business together with the elder sons of his brother. They have a shop in the central market in Maroua, but Alhaji Oumar has also restarted his previous involvement with gasoline imported from Nigeria.

Alhaji Oumar and his first wife Lami are Kanuri, but his second wife, Fatimatou, is a Hausa born and raised in Maroua. At the time when Alhaji Oumar married her 25 years ago, he was already involved in the cross-border gasoline trade. Fatimatou’s family lives in Dougoy, a district that adjoins Doursoungo. Alhaji Oumar and his wives also have their network of forced migrants.

In addition to the commercial activities of Alhaji Oumar, the family members are involved in petty trade: retail sale of commodities, gasoline and foodstuffs produced by the household. The children also attend both the public school of Doursoungo and the Koranic school. Fatimatou has given birth to thirteen children and Lami three. The three oldest have left home, while the family also takes care of three younger children of Alhaji Oumar’s disappeared brother.

The theoretical perspective of the article is based in the assumption that, like all of us, Alhaji Oumar’s family and other forced migrants are using their knowledge and resources in their interactions with their surroundings to achieve their goals. Andrej Vayda’s (1983) concept of progressive contextualization aims at explaining such interactions by placing them within progressively wider or denser contexts. Scale in a system is a measure of complexity. From the subjects’ perspective, scale is a measure of how far they can reach in their networks. My working procedure in this text is to try to track the social interactions of the actors in different social fields with different dynamics, complexity and extension (Grønhaug, 1978; Long, 2000). In giving explanations of the coping strategies of these forced migrants, the social fields of business, ethnicity, family and humanitarian aid are of particular relevance.

Multiple belongings in a prosperous border-area economy

Alhaji Oumar and his family share their styles of life with many of the other forced migrants on both sides of the Cameroon-Nigerian border in the Mandara Mountains. The border was agreed upon by the colonial masters at the start of the 20th century and maintained as the new nation-states were established in 1960. As in many other African border areas, the same peoples are on both sides of the border, sharing the same ethnic and religious allegiances, the majority being Muslims, but also with some Christian and Animist presence. In a study of the border districts of Mogode and Burha at the Cameroonian side, 60-70% of the interviewed stated that parts of their family reside on the other side of the border in Nigeria (Gonne, 2016:44).

For those living in the border area, possessing a double set of identity papers, one Cameroonian and one Nigerian, is not uncommon to facilitate movements back and forth. The border population’s own conception of the border between the countries is essentially that it is irrelevant when they are in touch with their extended family or ethnic group networks, an obstacle when they are harassed by the forces of law and order – representing different colonially inherited administrative systems – and a source of income when price differences between the two countries can be exploited (Ganava, 2021:115).

Commodities produced by Nigerian industry or imported from Asia, including medicines, drugs and gasoline, have crossed over to Cameroon, while soap, rice and other foodstuffs move in the other direction. The towns along the border on both sides have been busy transition ports for this trade, with Maroua one of its important distribution hubs in Cameroon. As with so many others, Alhaji Oumar and his family made their living from this trade, which meant that the closing of the border in 2012, to avoid Cameroon being used as a free heaven for the Boko Haram insurgents, had serious economic consequences for them and for large parts of the population. The situation grew even worse in 2014. Suicide bombings, burnings of villages and killings became frequent on the Cameroon side too. As in the case of Alhadji Oumar and his family, the victims of the crisis that I have met during my stays in Maroua have not only lost family members and property, but also important parts of their livelihoods.

After the first shocks from the closing of the border and the Boko Haram terror, the cross-border trade regained momentum by finding other routes. The recent opening of the Banki connection at the start of 2021 is yet another step towards the previous activity level. Alhaji Oumar is still involved in gasoline trade, but in a much less lucrative position at its destination in Maroua. The extension of his business network is drastically reduced. From being a go-between at the border, facilitating transactions between businessmen in Nigeria and the different countries of Central Africa, he is now involved in organizing the retail sales of gasoline at the local level in Maroua.

Who are the people on the run?

Already before Cameroon became militarily involved in 2014, refugees from across the border started to show up in Cameroon villages and towns. In the Far North Region , the Minawawo refugee camp, 60 km west of Maroua, was established by the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR) in July 2013. It was intended to host 12-14,000 but hosted more than 50,000 in 2020. Most of these arrived at the camp between 2014-2016, when the attacks on civilians became intense. Several camps for the internally displaced (IDPs) were also established close to the border, in Mora and Mokolo, as the attacks entered the Cameroon side. The refugee and IDP camps are only a part of the humanitarian crisis. While a considerable number were registered in these camps, many of the forced migrants live outside, in village and smaller towns, and in the regional capital Maroua[2].

It is not haphazard where the forced migrants ended up. Even if many of those who came to Maroua have difficulties making ends meet, those I have spoken with generally agree that these were somewhat better off from the outset, in terms of knowledge, financial means and already established networks, than the ones who ended up in the camps or those who have stayed on in the border areas. Many who came to Maroua were also part of the first wave of migrants, who left the border areas before the terror reached its peak and had a chance to bring with them some of their belongings. Their early departure may have had an element of pure luck or foresight, but they also possessed the necessary resources (financial/relational) to have this as a nearby option. Those who stayed on, for one or another reason, and managed to escape after being attacked, with barely any clothes on, were in a weaker position, and many ended up in the camps.

Those who stayed behind in the conflict area at the border have been squeezed between Boko Haram and Cameroon’s military forces. Those perceived as being involved with either side have risked being tracked down and killed by the other. Forced migrants in Maroua, like Alhaji Oumar and his family, have relatives who stayed on in the conflict area where they have had to deal with insecurity on a daily basis. The reasons given for why they stayed on are that they were dependent on their farmland for their survival and didn’t possess the financial resources to move on, nor to support themselves in a new place[3]. In this way, knowledge, financial means, and social networks shape destinies.

The forced migrants residing in Maroua reflects the ethnic make-up in the border area and the northeastern part of Nigeria. The Kanuri, Hausa, Fulani, Mafa and Mandara have arrived in large numbers. Most have settled in districts outside the center of town, such as Cainde, Doualare, Dougoi, Djarengol and Doursoungo – districts where they had contacts that hosted them initially, but the pattern also reflects a lower level of housing rental prices in these quarters than in the center of town. At the same time, these districts are not so remote as to prevent involvement in the informal petty trade economy that is focused around the central markets.

Living by social networks in Doursoungo

Doursoungo, where Alhaji Oumar and his family were able to settle, is one of the quarters in Maroua that have received many forced migrants. A Red Cross initiated census in 2014 conducted by migrant spokesperson Alhaji Kaka identified a little over 800[4] adults. Since then, people have come and gone, and he says he has lost overview. Most that came are of Kanuri origin. Kanuri are the ethnic group that started the Boko Haram insurgency and have continued to constitute its core (Seignobos, 2015). The host population of Doursoungo are mainly of Fulani origin. Both the Fulani and the Kanuri were islamized centuries ago.

There are several reasons behind the high number that came to Doursoungo. Already three decades ago, Kanuri from the border towns settled in Doursoungo as part of trade activities. Alhaji Kaka came in the late 1990s. The ones already established became bridgeheads for the ones that came as part of the crisis. Several migrants tell that, at their arrival, they moved in with someone they knew from their ethnic group, and then after some time were able to rent their own place, either solely for their family or together with other forced migrants. In addition to being a convenient distance to the central markets, Doursoungo also has many large houses in rather poor condition without electricity and running water that could be rented at affordable prices.

Both in Doursoungo and in other districts there is a difference between the forced migrants that were involved in cross-border trade before the crisis and those that came from other occupations. The ones with a stronger background in trade had relations already established in Maroua that could be of help at their arrival. While several had business connections that they describe as friendships, a few, as in the case of Alhaji Oumar, talk about relationships of long duration that already had evolved into family ties before the present crisis[5]. In this sense Alhaji Oumar and his family were among the “fortunate” with both business and family connections. Others survive on low-income jobs in the informal economy, like petty trade, transport (moped-taxi, trolley), night guardians etc., and find it harder to make ends meet, even if everybody in the household, young and old, does their part. The many households that have lost their main providers are of course even worse off. The Alhaji Oumar family have the main provider alive and both family and business relations that could be activated. The existence of previously established business relationships, ethnic relations and family ties have evidently influenced where people have ended up and their ability to cope with the new life situation.

Alhadji Oumar’s house faces the eating place of the Kanuri men outside Alhaji Kaka’s house. Every evening Alhadji Oumar joins the elders for their communal dinner. When important rituals like weddings, naming ceremonies and funerals occur in the Alhaji Oumar family, I observed how family members arrive from other parts of Maroua, but also from faraway towns in Nigeria, such as Maiduguri, Jos, Yola, Mobi, and likewise from Cameroon, all the way to Yaoundé, the capital. Most of them lived in Banki before the crisis but are spread in a large area dependent on where they had access to bridgeheads. Their willingness to travel considerable distances to take part in such gatherings is an important confirmation of the priority given to intra-ethnic and -familial relationships.

The relationship of the migrants to the host community in Doursoungo

A general welcoming attitude towards migrants in the Sahel, has been challenged by the insurgents not being a separate external group and almost impossible to single out from the rest of the population. As the violence aggravated with massive killings, it made host communities question who the people on the move were and what to expect from them. This contributed to the stigma of being a forced migrant, which was heightened when the migrant also was a Kanuri.

Reactions differ among the districts in Maroua. In Doursoungo, Kanuri talked about a generally welcoming attitude from the Lawan[6] and the host population. In the aftermath of the suicide bombs detonated in the central markets in 2015, there were cases where forced migrants were accused of being related to Boko Haram. As a result, Cameroon gendarmes conducted raids in which people without Cameroon identity cards were picked up and brought to the refugee camp of Minawawo. Teachers at the public primary school of Doursoungo tell that at the time it was necessary for them to protect the forced migrant children against the others. An NGO also accompanied the teachers in finding ways of smoothing the relationships between host and forced migrant children. Accusations of being Boko Haram can still be used when conflicts occur but have a less serious impact. As everybody had obtained Cameroon identity papers, the ones I spoke with did not see stigmatization as much of a problem.

I met forced migrants in other neighborhoods in Maroua who told about abuse and hostility from their neighbors, with frequent accusations of being related to Boko Haram. Trond Waage, in his study of refugees from the Central African Republic in Adamawa, Cameroon, also reports about exploitation by the host population (Waage 2018). In both cases, it seems to be groups of individuals that had a weak position from the outset. The Kanuri of Doursoungo is a self-confident group that cannot easily be bullied. When Adam Mahamat (2021) concludes that the forced migrants in North Cameroon are stigmatized by their hosts, I expect that this finding is partly due to his choice of the areas around refugee camps as localities for his research. The stigma may be more accentuated in such areas where the competition for scarce resources is stronger between refugees and local populations. My experience is that the eventual presence of stigma and abuse is highly situational and cannot be generalized.

I saw Fulani children going in and out of the household of Alhaji Oumar. A neighboring Fulani family had a corn mill and Alhadji Oumar family received corn pee for their goats. It means that at least some kind of integration has taken place. The presence of Kanuri for several decades in the border area in Doursoungo has contributed to trust and a relatively peaceful coexistence. The common religious affiliation is also of significance: praying together may promote integration. The institutionalized joking relationships that have been reported to exist between the Fulani and the Kanuri may also smooth everyday frictions.

Dynamics of the refugee crisis economy

Several NGOs have supported the forced migrants in Doursoungo and the neighboring districts. Fatimatou says they were surprised when they were once asked to gather outside the residence of the Lawan of Doursoungo to meet the NGO CAL-ART[7]. They expected a food distribution, but were instead told to organize themselves in groups. She became the leader of a group of 15 women that received two sewing machines. As she had some experience, she was asked to teach the women who were not familiar with the craft. Several of the members of the group argued that they should immediately sell the machines and divide the profit, which they did not do. The group became active, but as time went by and the machines needed maintenance, eventually Fatimatou ended up owning them. She says she learned from the activities of the group and has been sewing for the family and when she has received orders from others.

The NGOs’ main target groups in Doursoungo have been women and children. This is because many of the men, who were the families’ main breadwinners, were either killed or had disappeared, some probably more or less willingly recruited by Boko Haram. This made women and children vulnerable. Children were gathered in Koranic schools to counteract radicalization. Women were organized in self-help groups and given basic production equipment. In addition to sewing machines, some were provided with peanuts that could be roasted, split up and sold at retail, pasta machines, cooking equipment for street food sales, and so on.

It is a trend that donors and governments increasingly seek to deliver development projects through community-based organizations such as self-help groups (Gugerty et. al. 2019). As the current ideology, it is not only supposed to provide those vulnerable with economic means but also contribute to empowerment and improved psychosocial health. There are many good intentions behind the initiatives and the positive effects for the individuals and the community are present, but I can’t deny the impression that this becomes yet another “game” people know they must take part in to get access to valued goods. In Doursoungo, memberships in these self-help groups became a part of the daily struggle for survival and to a lesser extent a route into a self-reliant future.

Emergency relief has been provided by the UN system and numerous international and Cameroon NGOs have also been involved. In mid-2016, there were 29 NGOs operating in the Far North, including 14 internationals, primarily from surrounding countries[8], but also Europeans like the Norwegian Refugees Council and Red Cross International. As the refugees were in Minawawo, at least in theory, the NGOs’ primary target group were the IDPs. Also this in theory, and not in actual praxis.

Multiple belongings and double sets of identity papers don’t imply that the border population in the Mandara Mountains lack a notion of nationality, but they may switch according to the situation[9]. During the present crisis, the regionally evolved network-based ways of existence that traverse national frontiers has been confronted with the externally created bureaucratic categories of the aid providers that distinguishes between foreign Nigerian refugees, Cameroonian internally displaced IDPs and host populations. The categories lack legitimacy and people that have lost everything and have been forced to flee in fear obviously try to make the best of an unfavourable situation. How they navigate has its gains and losses. The UNHCR has a reputation for providing help more effectively than what the NGOs and governmental institutions can do in the IDP camps. This might be a better option if you have a Nigerian identity card and manage to get in there. On the other hand, being in a camp restricts the possibilities of taking part in the informal economy, which is easier if you stay among locals in villages and towns.

But neither Minawao nor the IDP camps have been strictly separated from the rest of society. As inhabitants of the camps have been permitted to come and go as they wanted after having obtained a registration, a survival strategy after managing to establish themselves outside the camps have for some been to continue to be registered in the camps to get access to the provisions handed out. Putting it on the edge, an NGO employee jokingly told in 2019 that when they distributed food in the camps, it arrived back in Maroua before they themselves managed to return to town.

Living in camps often implies passivity. Elisabeth Colson (2003:1) writes:

What happens after uprooting depends largely on whether people resettle on their own using their existing social and economic resources, are processed through agencies, or are kept in holding camps administered by outsiders.

In this sense the open character of both the IDP and refugee camps, and the way they progressively have turned into towns and villages, where the inhabitants of the camps take part in commercial activities, cultivate their own crops, and take part in the general work life, have counteracted such negative effects. The forced migrants living outside the camps, like the population of Doursoungo, have to a large extent managed on their own, but have in addition taken advantage of the opportunities organized by the NGOs, and some have in addition kept up their relations to the refugee camps. It means that a wider range of options have been available for this group. As Colson (op. cit.) indicates, an existence outside the camps also offers chances for a repurposing in life, as it has done for some of the forced migrants I have met in Maroua, even to the extent that it has made Maroua the preferred option for their post-conflict settlement.

Hosts sharing food, even with strangers, is a strong cultural value in the Far North, but when sharing has been going on and only the newcomers are helped by the humanitarian organizations, conflicts occurred. When I started my fieldwork in Doursoungo, as a white person I was identified with the NGOs and approached by the host population who explained that they also had their needs. While open conflicts have been avoided between forced migrants and host population in Doursoungo, they have been frequent in the areas where the camps are situated (Mahamat 2021). In 2020, an NGO worker told me that while it had been possible to distinguish between newcomers and host population inside the town of Maroua, it was almost impossible to know who is who when distributing foodstuffs in the Mandara Mountains. He also asked what the point was when all had a marginal existence. It indicates that also the approaches of the helpers have been adjusted along the way.

The sewing machines that ended up with Fatimatou were financed by the local NGO CAL-RT that has recruited staff and students at the University of Maroua to organise projects, make surveys to identify needs and carry out activities. In this way the NGOs/UNHCR systems have provided employment for locals with relevant education. University of Maroua staff have been hired as consultants by the NGOs, and the large number of students in social science disciplines, that in general have problems finding employment, have also encountered opportunities. It is somewhat ironic that it was such Western-educated elites that the Boko Haram insurgency initially hoped to counter. Also, traditional and modern administrations play their part. By being involved, they get access to appreciated resources. In a district like Doursoungo, with many forced migrants and several NGOs present, this has motivated these administrations to take care of the newcomers.

Several different types of participants with different aims and resources – forced migrants, host population, students, professors, traditional and modern administrators, NGO workers – are part of the humanitarian aid field. It is a field of large scale and high complexity that stems from ideologies developed at macro levels. The forced migrants have adapted to these systems, but to cope with challenging circumstances they have also continued to navigate in this field according to the local network-based codes that traverses the distinctions between IDPs, refugees and hosts.

End of story?

Continuities exist in the ways that forced migrants have made use of previously established networks – business, family, friends, ethnicity, religion – but discontinuities are also evident. They have been under pressure, as families have been dispersed, have lost their main providers and their previous livelihoods. In Maroua, some have managed to establish a new and solid economic basis for themselves and their dependents. Others struggle to make ends meet. People who have experienced forced migration maintain concrete links to the past, while continuous repurposing takes place. Personal histories, relational networks and current circumstances are intertwined and have been decisive for the forced migrants’ abilities to create a new livelihood for themselves, to deal with the established systems of humanitarian aid, and the locals of their host communities.

Forced migrants in Maroua have been able to activate networks related to their own ethnic group, family, friends and businesses to varying extents. The Alhaji Oumar family is among those that have managed well, but the fact that the NGOs during 2019 terminated their activities in Doursoungo and moved to the border areas, shows that they are not the only ones.

As the violence calmed down after the deaths of two of the main Boko Haram leaders, Shekau and Al-Bernawi, forced migrants started to return to their homes at the border. Alhaji Oumar’s family also started to prepare for a return to Banki in Nigeria, but not everybody has the intention of going back to their former homes. Some have managed to create a new existence for themselves and their families in Maroua and consider staying on as a better option. In a town they have access to educational institutions at all levels and facilities like electricity. By being a centre for commercial activities, Maroua also provides opportunities.

When people hesitated to reestablish their former life at the border, it was related to a fear that the violence was not over yet. The Cameroonian government’s focus on a military response has been partly successful, but the marginalization of the region that made part of the population take part in the insurgency has not been addressed. The recruitment from inside the communities to Boko Haram also created worries. As one of the forced migrants said: You know who slaughtered your grandmother. How are you going to go on living with them without a proper process of reconciliation?

References

Arntsen, B. (2018). Aggravated uncertainty. The dubious influence of a modern management regime on the Lake Chad fisheries. In H. Fyhn, H. Aspen & A.K. Larsen (Eds.) Edges of global transformation: Ethnographies of uncertainty. Lexington books.

Colson, E. (2003). “Forced Migration and the Anthropological Response”. In Journal of Refugee Studies Vol. 16, No 1.

Ganava, A. (2021). Cross-border “smuggling” of goods in the Far North of Cameroon: A survival strategy for vulnerable people in Logone-Chari and Mayo Tsanaga. PhD thesis, University of Maroua, Cameroon.

Gonné, B. (2016). “Anticipation urbaine et accaparement des kare périphérique-Est de Maroua (Extrême-Nord Cameroun)”. In Zieba, Liba’a, Gonné (eds.) Pressions sur les territoires et les ressources naturelles au Nord-Cameroun. Enjeux environnementaux et sanitaires. Éditions CLÉ, Yaoundé.

Grønhaug, R. (1978). Scale as a variable in analysis: Fields in social organization in Herat, Northwest Afghanistan. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

Gugerty, M. K., Biscaye, P. & Leigh Anderson, C. (2019). “Delivering development? Evidence on self-help groups as development intermediaries in South Asia and Africa”. Develop Policy Review, 37, issue 1.

Long, N. (2000). Exploring local – global transformations: a view from anthropology. In Arce, A. and Long, N. (eds.) Anthropology, Development and Modernities. Exploring discourses counter-tendencies and violence. Routledge, London.

Magrin, G. and Pérouse de Montclos, M-A., (2018). “Crisis and development. The Lake Chad Region and Boko Haram”. Agence Francaise de Development.

Mahamat, A. (2021). Déplacés et réfugiés au Cameroun: profils, itinéraires et expériences à partir des crises nigériane et centrafricaine, Canadian Journal of African Studies / Revue canadienne des études africaines, DOI: 10.1080/00083968.2021.1880948

Mohammed, K. (2014). The message and methods of Boko Haram. In Boko Haram:Islamism, Politics, Security and the State in Nigeria, edited by Perouse de Montclos. Leiden: African Studies Center.

Seignobos, C. (2015). Boko Haram et le Lac Tchad. Extension ou sanctuarisation ? Afrique contemporaine, 2015/3 (No 255), 93-120.

Vayda, A. (1983). Progressive contextualization: Methods for research in human ecology. Human Ecology, 11, 265-281.

Waage, T. (2018). “War refugees in Northern Cameroon: visibility and invisibility in adapting to the informal economy and the ‘tolerant’ state”. In Bjarnesen, J. and Turner, S. Invisibilities in African Displacements. From structural marginalization to strategies of avoidance. Zed Books.

- The video-based fieldwork took place in Doursoungo in 2020 and 2021. In 2019, interviews were conducted with the help of an interpreter with 16 forced migrants with Cameroonian identity cards and 15 with Nigerian identity cards in different neighborhoods in Maroua. ↵

- To give the reader an idea of the sizes of the host population and the newcomers, and as statistics are not available, I asked people in Maroua for estimates. Maroua is presently said to have more than a million inhabitants. Twenty years ago, the number was said to be less than 300,000. The number that has arrived since 2014, related to the Boko Haram crisis, is estimated to be 30-50,000. There is considerable uncertainty associated with these numbers. ↵

- The IDP camps have had a reputation for not distributing enough food and supplies, and a Nigerian identity card was needed to get into the refugee camp of Minawawo. ↵

- Alhaji Kaka also estimates the total population of adults in the district to be around 10,000, to give a rough idea of the numbers of hosts and forced migrants. ↵

- Data from my survey in 2019. ↵

- The Lawan is the level below the Sultan of Maroua in the traditional administrative system. According to the present Lawan of Doursongo, the Lawanate of Doursongo existed already at the arrival of the German colonizers at the start of the 20th century (Interview 07.11.21). ↵

- CAL-RT (Collectif Africain de lutte contre la Radicalisation et le Terrorisme). ↵

- https://odihpn.org/magazine/the-challenges-of-emergency-response-in-cameroons-far-north-humanitarian-response-in-a-mixed-idprefugee-setting/ ↵

- A similar tendency has been observed at the Cameroon-Chadian border south of Lake Chad where the colonially established border traverses the living area of ethnic groups (Robi, forthcoming PhD theses, University of Maroua, Cameroon). ↵