7 Learning Strategies: Useful Resources in Cognitive Processes

Pierre Edher Gedeon

| Abstract/Rezime

Learning strategies are tools that learners use to acquire, integrate and remember the knowledge being taught. In addition to the teaching practices applied in almost all the schools visited, the strategies used by students with disabilities are observed in order to assess their cognitive processing. This contribution provides us an opportunity to share some of the preliminary results obtained. results that had been obtained. Keywords: disability, pedagogical practice, student, learning strategy, teacher Yon estrateji aprantisaj se yon mwayen yon elèv itilize pou li kapab aprann, memorize ak enteryorize sa yo anseye li. Aprè nou fin konstate pratik pedagojik yo aplike nan tout lekòl nou obsève yo, nou te gade estrateji elèv ki nan sitiyasyon andikap yo devlope pou yo aprann, nan objektif pou nou evalye pwosesis konyitif yo. Kontribisyon sa a pèmèt nou pataje rezilta pwovizwa nou jwenn sou pwoblematik sa a. Nou ranmase enfòmasyon nou analize nan atik sa a nan lekòl Notre Dame de Lourdes (ENDL) ki nan vil Jeremi, nan klas 2zyèm ane. Li konsène17 elèv, soti nan laj 6 zan rive 9 van. Mo-Kle : andikap, pratik pedagojik, elèv, estrateji aprantisaj, anseyan |

Introduction

The Haitian education system constitutes a barrier for students who do not find their place in it. Generally speaking, those who do not work at the same pace as others are often excluded or harshly judged. They are excluded because they are not able to apply ready-made formulas like the others and are judged without discernment, often because of the application of overly general teaching practices that penalize them. What remedy can be offered to these students?

Some theoretical indicators

Strategies refer to a set of observable and unobservable actions or means (behaviors, thoughts, techniques, tactics) employed by an individual with a particular intention, and which are adjusted according to the variables of a situation. They are useful for students’ academic success and are carried out in different ways (Cartier, 1997).

Strategies are often specific to the reality of the person who is using them. A first idea is that they are used in a natural and authentic context, i.e., within the usual courses and by carrying out real activities. This principle related to the contextualization of learning approach is noted in the work of Tardif (1992) and Weinstein (1994). These researchers recommend teaching general strategies (such as learning strategies) in the context of acquiring specific knowledge (such as that which belongs to the field being studied). A second idea is that the teacher should encourage students to reflect on the strategies they use spontaneously (Bazin & Girerd, 1997). The third idea is that students should be explicitly taught learning strategies that they do not know or use, but that may be effective in context. Thus, Weinstein and Hume (1998) propose the use of three teaching methods: Direct instruction, which consists of telling which strategy to apply and how to use it; cognitive and metacognitive modelling, which aims to make explicit the reasoning that accompanies the planning and execution of a task, to highlight the importance of controlling the execution of the task and to communicate attitudes (Hensler, 1999); and guided practice with feedback, which proposes discussion of the characteristics as well as possible and impossible applications of the strategy to increase, if necessary, a repertoire of strategies (Boulet, Savoie-Zajc and Chevrier, 1996). Good learning strategies are necessarily useful for the development of cognition. Legendre (1993) defines cognition as “a sequence of the following processes: 1) information gathering; 2) storage; 3) interpretation; and 4) understanding. Generally speaking, cognition refers to a set of activities related to acquisition and organization of knowledge” (1993). This idea is in line with Costermans’ idea that the acquisition and organization of knowledge models behavior (Costermans, 2000).

Objective and methodological points

This study focuses on learning strategies in the context of the stimulation of cognitive processes and the importance that should be given to the student’s involvement during this learning process. Researchers such as Weinstein (1994) have shown that students who are successful in class are those who use effective learning strategies to successfully complete the different activities proposed to them (Cartier, Debeurme, & Viau, 1997). The fact that students demonstrate autonomy in their learning is another reason. They know and make good use of learning strategies that enable them to acquire knowledge and develop skills; when the students construct them themselves, they are useful for lifelong learning.

Students with cognitive disorders, a group who are poorly regarded, stigmatized, and even diminished in their person according to what the teachers say, form the sample of our investigation. We also take into account the performance required to demonstrate executive functions, the didactic apparatus, and the teaching methods.

Tools and data collection

As part of the research conducted in the departments of Grand’Anse, Nippes and Sud entitled “Students with disabilities and teaching practices of teachers in the departments of Sud, Nippes and Grand’Anse”, these tests were designed to identify students with disabilities and monitor the frequency of the signs noticed by the research department. These tests also helped identify disorders in students enrolled in the first cycle of basic education, particularly those in AF2.

Intelligence tests showing disorders related to understanding and processing information are also administered.

The BREV (batterie rapide d’évaluation des fonctions cognitives) is a clinical tool used by health professionals to conduct neuropsychological examinations in children aged 4 to 9 years to identify students with cognition-related disorders. However, it is not an intelligence test. This test has two objectives: 1. to identify children suspected of a deficit in cognitive functions; 2. to determine the profile of this deficit in order to direct the child to a competent professional who will confirm whether the initial diagnosis is correct. It also makes it possible to refine the diagnosis of a child with a learning difficulty, a child with a neurological disorder at high risk of cognitive consequences, in particular epilepsy, on a systematic basis as part of screening in children from the age of 4 years. This battery of tests allows an evaluation of each of the cognitive functions thanks to its 18 separately validated subtests: Oral language (reception and production), non-verbal functions (seriation, graphics, visual discrimination, visuo-spatial reasoning, executive functions), attention, verbal and visuo-spatial memory, main learning (reading, spelling, calculation).

All this has been done in order to determine whether the subjects of the population being investigated present cognitive disorders, with a concern for the difficulties related to information processing caused by a non-adaptive pedagogical system, and the environmental context.

The data and its interpretation

Cognitive disorders

Of the 17 students observed, ten were from Grade 2A and seven from Grade 2B. They were all female.

- Five, or 29%, had a cognitive problem related to comprehension;

- Six, or 35% presented a cognitive disorder related to attention;

- Four, or 24%, had a cognitive impairment related to memory;

- Two or 12% had a cognitive disorder related to language.

Pedagogical practices

The intellectual progress and psychological development of these students is hindered because of the cognitive disorders detected. Cognitive disorders affect memory, reasoning, language, motor skills, attention and executive functions. They are mainly linked to the weakness of an education system characterized by an inflexible teaching/learning system and a rigid style of teaching. The teachers that were observed consider their classes as a homogeneous entity. This implies that individualized support has not been applied.

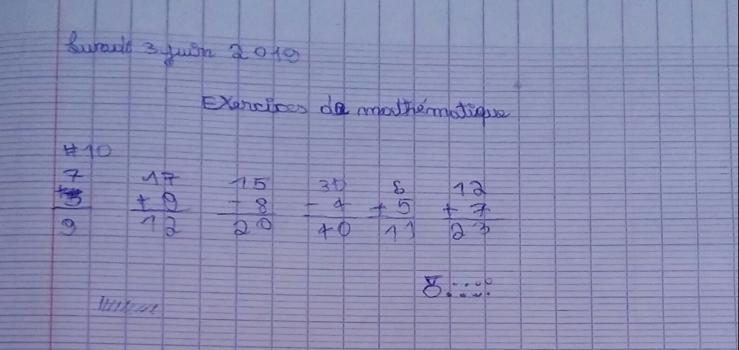

Some children do not know the basic concepts of mathematics, confusing cardinal and ordinal numbers. They are unable to make the connection between the symbol and the quantity. It is therefore difficult for them to compare two values (and even to understand that one number can be greater than another), to evaluate small quantities, to master the numerical system, i.e., to understand and use positional numbering, with the place of units, tens, hundreds, or to calculate even very simple operations. It is clear that mastering counting requires knowledge of the numerical system, the ability to point to each element and only one, as the count progresses, and to understand the notion of quantity and the cardinality of the number: if I count up to 5 by counting the tokens, it means that there are 5 tokens.

Executive functions (language, memory, perception, attention, etc.) are higher functions whose roles are to administer, supervise and control the other functions. They are also responsible for difficulties in mathematics.

The majority of teachers participating in the study are unaware of the simplest steps to screen for disorders and to consider an inclusive method in order not to discriminate against the student. They are unaware of the importance of learning strategies that emphasize participation in children’s cognitive development and psychological well-being. They lack the means to help a child with cognitive problems.

Categories of knowledge

When it comes to the areas of cognitive, socio-affective and psychomotor, cognitive psychology considers that there are basically three main categories of knowledge:

Declarative knowledge which essentially corresponds to theoretical knowledge such as knowledge of facts, rules, laws, principles. For example, knowledge of each part of the human body.

Procedural knowledge corresponds to active understanding, the steps to carry out an action. In pedagogy, this knowledge is described as know-how, it is knowledge of action, dynamic knowledge: drawing something, taking dictation.

The objectives related to the development of procedural knowledge require that the student be continually placed in a context of performing real-life tasks (Bazin & Girerd, 1997). The teacher then becomes much more of a mediator between the knowledge to be acquired and the student than a direct transmitter of information as in the transmission model.

Conditional knowledge refers to knowing about when and why. When and in what context is it appropriate to use this or that strategy, this or that approach, to take this action or another? Why is it appropriate to use this strategy, this approach, to take this action? These questions relate to conditional knowledge.

In the school setting, conditional knowledge is the most neglected category of knowledge. Example of conditional knowledge:

1- distinguish a square from a rectangle

2- know the position of a number in a numbering table.

In this active process of knowledge construction, memory plays a central role.

Individual and psychological impacts

Many children with mathematical difficulties experience a psychological blockage caused by anxiety and feelings of incompetence. They do not have any disorders that could explain dyscalculia, but they are still struggling with failure in this area. These children feel that they “suck at math”, they panic when they have to find an approach, understand a reasoning or a notion. They learn to apply and copy without understanding.

The cognitive problems observed and identified in the study have a detrimental impact on each individual learner and on the class as a whole. The emotions released in relation to real-life situations affect their psychological and mental state. The academic performance of these students pays the price. It is understandable why the disorders are experienced as a personal failure.

Stigmatized and sometimes traumatized, these students drop out and show themselves more capable of carrying out activities where they feel more comfortable; they give in to restlessness, disruption, mockery and distractions. They become aggressive and show a real lack of interest in activities involving the cognitive system.

Conclusion

A learning strategy in a school context is a metacognitive or cognitive action used in a learning situation, oriented towards the goal of carrying out a task to perform knowledge operations according to specific objectives.

We hope that this contribution has provided answers to the issue related to the use of learning strategies. On the one hand, we have stressed that the acquisition of learning strategies is an important factor because it makes it possible not only to learn in a school context, but also throughout life. On the other hand, teachers who want to help students must teach them not only the knowledge and skills of their field of study, but also strategies that enable them to learn. By doing so, they increase their students’ learning power and help them to become learners for life.

References

Bazin, Anne & Robert Girerd, (1997), “La métacognition, une aide à la réussite des élèves du primaire”, pp. 63-93, M. Grangeat et P. Meirieu (dir.), La métacognition, une aide au travail des élèves, Paris: ESF.

Boutet, Albert, et al., (1996), Les stratégies d’apprentissage à l’université, Québec: Presses de l’Université du Québec.

Cartier, Sylvie, et al., (1997), “La motivation et les stratégies autorégulatrices : cadre de référence”, p. 33-45, L. Sauvé et al. (dir.), Deuxième rapport trimestriel de progrès des activités de recherche du projet, Québec: Société pour l’apprentissage à vie.

Cartier, Sylvie, (1997), Lire pour apprendre : description des stratégies utilisées par des étudiants en médecine dans un curriculum d’apprentissage par problèmes, Thèse de doctorat inédite, Montréal: Université de Montréal.

Costermans, Jean, (2000), Les activités cognitives : Raisonnement, décision et résolution de problèmes, 2e édition, Bruxelles: De Boeck Supérieur.

Hensler, Hélène, (1999), “Métacognition : enseigner dans une perspective métacognitive”, Revue de formation et d’échange pédagogiques, avril, pp. 2-5.

Légendre, Renald, (1993), Dictionnaire actuel de l’éducation, 2e édition, Montréal: ESKA.

Tardif, Jacques, (1992), Pour un enseignement stratégique : l’apport de la psychologie cognitive, Montréal: Éditions Logiques.

Weinstein, Claire Ellen & Laura Hume, (1998), Stratégies d’études pour un apprentissage durable, Washington: American Psychological Association.

Weinstein, Claire Ellen, (1994), “Stratégies d’apprentissage et stratégies d’enseignement”, pp. 257-274, P. R. Pintrich, D. R. Brown et C. E. Weinstein (dir.), Élève, Motivation, Cognition, et Apprentissage, Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum.