MIXED METHODS AND CROSS-CUTTING APPROACHES

22 Contribution analysis

Thomas Delahais

Abstract

Contribution Analysis is a theory-based evaluative approach particularly suited to the evaluation of complex interventions. It consists of progressively formulating “contribution claims” in a process involving policy stakeholders, and then testing these hypotheses systematically using a variety of methods (which may be qualitative or mixed).

Keywords: Mixed methods, complex interventions, contribution claims, abductive approach, context, causal pathways, causal packages, narrative approach

I. What does this approach consist of?

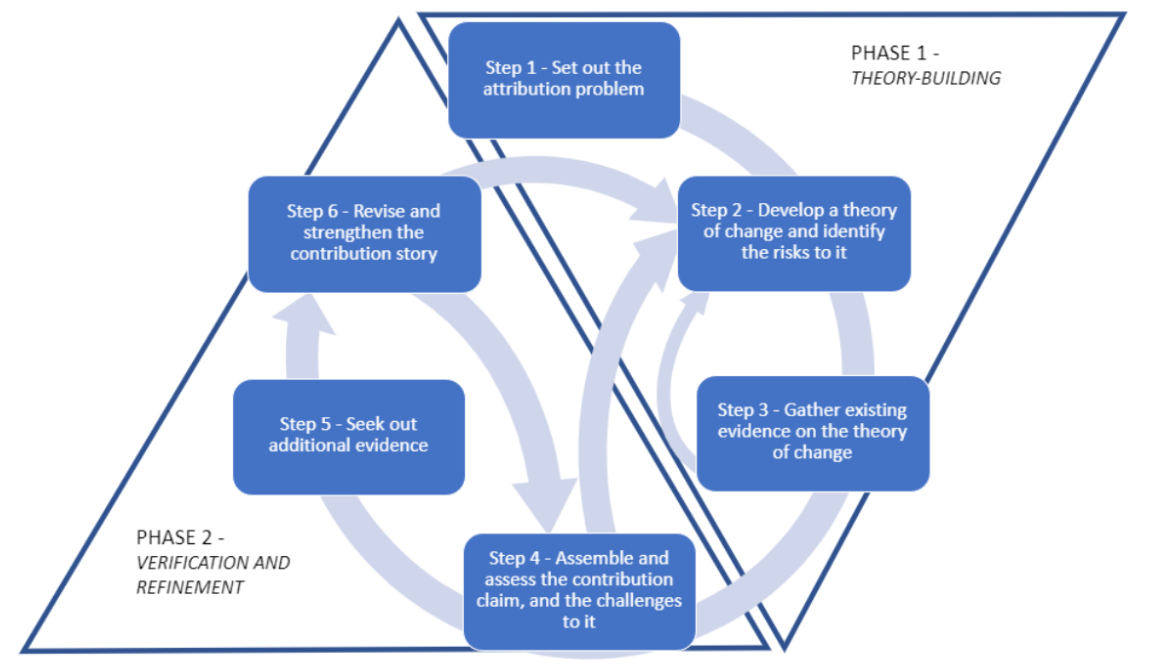

Contribution analysis is a so-called theory-based evaluation approach[1] (TBE): it is organised around a process of 1) developing a set of hypotheses about the effects of an intervention being evaluated (how these effects are achieved, in which cases, why…) – known as the ‘theory of change’; 2) testing these hypotheses through the collection and analysis of empirical information; and 3) updating the original theory by indicating which hypotheses are verified.

Like Realist Evaluation or Process Tracing, for example, Contribution Analysis is part of the new generation of TBEs that emerged at the start of the 2000s (sometimes referred to as theory-based impact evaluations – TBIE). It considers the interventions being evaluated as complex objects in complex environments. Central to Contribution Analysis is the postulate that interventions do not intrinsically ‘work’; their success or failure always depends on a diversity of drivers and contexts, which the evaluation needs to document. This is in contrast with Counterfactual approaches, for instance, which aim at identifying “what works” in isolation from their context. But what distinguishes Contribution Analysis from other approaches is that it also rejects the idea that the role of evaluation is to establish impact irrefutably: in a complex context, its aim is not to prove the effects of interventions, but to reduce uncertainty about their contribution to any changes that have occurred. It is in fact uncertainty that can be considered to be detrimental to decision-making and policymaking more generally.

I.I. Theory-building

The whole process of Contribution Analysis thus consists of gradually reducing uncertainty about the effects of the intervention being evaluated. As with all TBEs, the first phase, theory-building, consists of asking a question about the cause-and-effect relationships that are to be investigated and developing causal assumptions in response to this question. The latter usually concerns the contributions of the intervention to the desired changes. Let us imagine a governmental plan to prevent or deal with sexual violence in higher education institutions. The question asked might be: “How has the plan contributed to the effective reduction of sexual violence and better management of its consequences?”

The level of violence and the responses provided in institutions, however, are societal changes that are only partially dependent on any ministerial plan. Indeed, Contribution Analysis does not assume that these changes are due to the intervention. Rather, it assumes that any change is the result of a multitude of intertwined causes, including (perhaps) the intervention. Thus, Contribution Analysis starts from the change (in this case, the evolution of sexual violence) to look for contributions, rather than from the intervention being evaluated (the governmental plan).

The focus of Contribution Analysis in this initial phase is therefore to make explicit what the contribution of the intervention might be (among other factors) and to ensure that such a contribution is plausible. Plausible means that the contribution, while not verified, is nevertheless likely: it could occur in the context of the intervention being evaluated.

The more complex the setting of the intervention, the longer this initial investigation may take. The plausibility of an assumption is not judged in abstracto: it is assessed on the basis of the convergence between the observations, experiences and informed opinion of the stakeholders, its proximity to assumptions validated in other settings presenting similarities to the intervention being evaluated, the possible significance of the intervention in relation to other factors, initial indications of a possible effect, etc.

This phase is usually based on an initial collection of empirical data (exchanges with stakeholders, a literature review or a document analysis) that leads to “contribution claims” and alternative explanations (i.e. claims about other factors that could plausibly explain the observed changes). In our case, an evaluation would look at changes in sexual violence and institutional practices over the past few years to identify possible contribution claims. If a number of institutions have drastically changed their practices in this area, it may be because the plan included an obligation to put in place strategies to combat sexual violence and to report on progress annually; or it may be that actors already in favour of active approaches to sexual violence in the administration have used the plan to support their internal agenda; or it may be that student groups have used the plan to bring reluctant administrations to act. Each of these three assumptions, if supported by examples, a convincing theoretical framework, etc., can become a contribution claim.

At this stage, the level of uncertainty regarding the effects of the intervention has already been reduced compared to the initial situation: some claims have been rejected, others appear more or less plausible at the current phase of the evaluation. Those that are retained are studied in the next step.

I.II. Theory-testing

Only those claims that are sufficiently plausible (or those considered particularly important to stakeholders) are tested in depth. In Contribution Analysis, a very wide range of tools or methods, both qualitative and quantitative, can be used to estimate changes and to collect evidence in favour of or against the contribution claims, in combination with other factors. In this process, contribution claims are not validated or discarded. Rather, they are progressively fleshed out, for example from “the intervention contributes in such and such a way” to “when conditions x and y are met, the intervention contributes in such and such a way, unless event z occurs”, leading to “causal packages” that bring together several factors associated with observed changes. Contribution Analysis can also focus on identifying the impact pathways and underlying mechanisms that explain these contributions. For example, in our case, perhaps the testing phase would show that putting the issue of sexual violence into the framework of the accountability relationship between the ministry for Education and the educational institutions had direct consequences in terms of setting up a helpline for reporting violence; but that not all ministries really grasped this issue in their accountability relationship with institutions within their remit. Ideally, the next step in the data collection process would be to check whether such helplines for reporting violence exist in the institutions supervised by other ministries, and why.

Contribution Analysis does not impose any particular approach to infer causality. One possible way is to identify a series of empirical tests, as in the Process tracing approach. These tests each define a condition that must be satisfied in order to conclude that the intervention contributes to the observed changes. Tests may also be conducted for other factors that could plausibly explain the changes. All the tools of evaluation and, more broadly, of the social sciences, whether qualitative or quantitative, can be used to conduct these tests: interviews, case studies, documentary analyses, as well as surveys, statistical analyses, etc. can be used. The combination of different tools makes it possible, through triangulation, to strengthen (or reduce) the degree of confidence in the contribution and to arrive at the findings and conclusions of the evaluation. Realist Evaluation can also be used here to identify mechanisms underlying causal relationships.

A final specificity of Contribution Analysis is that it ultimately generates contribution stories. The contribution story initially brings together the contribution claims, which are gradually reinforced through collection and analysis. It is intended to consolidate, complement or challenge the dominant narratives underlying the intervention being evaluated. Unlike a counterfactual evaluation, for example, which seeks to be convincing through quantification, Contribution Analysis relies on narratives supported by evidence, which can then be used in the making of public policy. In our case, perhaps the contribution narrative would show how stakeholders already involved in the fight against sexual violence have seized on the governmental plan to tip the balance in their favour in the internal governance of institutions, to the detriment of a national narrative based on state control of the practices of educational institutions.

II. How is this approach useful for policy evaluation?

Contribution Analysis is mainly used ex-post, although there are attempts to use it in support of policy implementation. It is particularly useful in cases where the contribution of an intervention to the expected changes is very uncertain, or seems unlikely, but the contribution is of strategic interest to stakeholders: for example, because expectations are very high for the contribution, or because the continuation of the intervention depends on it.

The work done in the theory-building phase, because it allows for the formulation of plausible contributions that often deviate from stated objectives, is particularly useful for strategic management or redesign of interventions.

Contribution Analysis lends itself particularly well to collaborative or participatory approaches, allowing stakeholders to discuss contribution claims and the conditions under which they are likely to be verified or not. The contribution stories it produces, if discussed and owned by stakeholders, provide a useful basis for strategic reorientations. In their final form, the contribution claims, because they are explanatory and contextualised, are also useful to improve the intervention or to modify the practices of the actors involved.

III. The example of a Foundation’s contribution to research in the life sciences

A Foundation[2] provides long-term support (funding, guidance) to high-level research teams and institutions in the field of life sciences. The Foundation’s management is aware that the results of the work funded cannot be solely attributed to their support: the research teams are in fact the main driving force behind the results obtained; they generally rely on a plurality of funding sources; they are part of research trends, build on past research and work in conjunction with other teams around the world. Finally, the contributions that the Foundation can make are inseparable from the research context (underfunding of research in France, international competition, etc.). Nevertheless, its managers believe that its contribution can be significant, and they wish to explore it.

Given the diversity of the projects supported (individual or collective support, research work, equipment, multidisciplinary approaches, etc.), several theories of change are initially designed and fed by an exploratory data collection exercise (documentary analysis, interviews). This initial phase leads to a first draft of a ‘meta-theory’ of change (bringing together the different theories developed), in which a certain number of contribution claims are proposed. These differ in particular according to the maturity of the supported project, and the type of support. For each of these contribution claims empirical tests are developed, with a view to estimate the degree of confidence that can be placed in the veracity of these contributions. These claims are then scrutinised through related tests in a series of case studies of projects supported by the Foundation.

The cross-analysis of the case studies allows the Foundation’s contributions to the projects it supports to be refined and detailed. In total, eight main contributions are identified, through different channels: for example, funding from the Foundation can contribute to the sustainability of a project through its long-term commitment, but also because it brings credibility to the project, which can then attract other funding. The Foundation does not always activate these eight contributions, but its value added is more important when several are observed on the same project. The contribution story emphasises that these contributions draw on a set of common explanatory factors: for example, the relevant choice of researchers who know how to use additional funding to go further, or to test what they would not otherwise have been able to test; or the relationship of trust that has been established, with a great deal of freedom given to the research teams (which is reflected in particular in minimal expectations in terms of reporting on the funding). This human dimension is also what explains why its contributions are more significant in supporting research teams than institutions. The evaluation thus feeds into to the Foundation’s strategic development by identifying the situations in which its contribution can be most important and the choices that a reorientation would imply in terms of human and financial resources.

IV. What are the criteria for judging the quality of the mobilisation of this approach?

The quality of Contribution Analysis is essentially judged by the ability to work along a continuum of plausibility, which means being able to start with a number of assumptions about the factors underlying the observed changes, including the intervention, to review them, identify the most plausible ones, and then test and build on them.

In recent years, the term Contribution Analysis is sometimes used as a seemingly flattering synonym for theory-based evaluation. The main criteria to differentiate them include:

- the iterative (so-called abductive) approach of Contribution Analysis (assumptions are constantly revised throughout the evaluation);

- the fact that the search for contributions starts with the expected changes and works backwards to the intervention, rather than the other way around;

- the collection of information to progressively contextualise and explain the contribution claims;

- the care taken to test alternative explanations;

- the narrative dimension of the results, in the form of a contribution story.

V. What are the strengths and limitations of this approach compared to others?

Contribution Analysis provides credible and useful findings for the design of public policy in very specific situations, which initially seem very complicated to evaluate. It owes its credibility to it being an iterative process, which can be made transparent in a participatory approach. Due to stakeholders being involved at each stage and the traceability of the tests carried out, as well as the humility of the approach, it gives rise to a high degree of trust, which is a precondition to the use of the results.

Nevertheless, it should be borne in mind that the process of Contribution Analysis is itself uncertain: it is not known at the outset which contribution claims will be tested and how. It is usually necessary to keep an open mind at the beginning of the evaluation to understand the context in which the intervention is situated and which interventions or factors explain the observed changes. This initial phase, which consists of describing the changes observed, is what makes Contribution Analysis so interesting compared to other approaches that tend to examine interventions out of their contexts. However, this phase can be extremely time-consuming, especially as it relies heavily on secondary sources, external to the evaluation, and the right degree of descriptive thickness must be found, given that evaluation does not usually aim at being comprehensive.

As with any TBE, there is a risk of overestimating contributions, although starting with the changes rather than the intervention itself reduces this risk. One solution is the systematic application of empirical tests to the intervention and to alternative explanations. However, this can be cumbersome and confusing, especially when the tests are too numerous or poorly calibrated (i.e. they do not allow for sufficient variation in the degree of confidence in a contribution claim).

It should be noted that whereas realist evaluation and process tracing are used more at the project level or to test a single impact pathway, Contribution Analysis is used more at the programme or policy level, when there are many actors involved and many impact pathways. This broader focus is what makes Contribution Analysis interesting, but it reinforces the uncertainties described above.

Some bibliographical references to go further

Contribution Analysis was first developed by John Mayne in the late 1990s. The following two articles can be read, the first one marking the beginning of the consideration of complexity by Contribution Analysis and the second one presenting a state of the debates and developments of Contribution Analysis in 2019:

Mayne, John. 2012. Contribution Analysis: Coming of age?. Evaluation, 18(3): 270‑80. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1356389012451663 )

Mayne, John. 2019. Revisiting Contribution Analysis. Canadian Journal of Program Evaluation, 34(2). https://doi.org/10.3138/cjpe.68004

The following articles reflect the progressive operationalisation of the approach in the 2010s. The first reports on a number of practical obstacles and ways in which practitioners can overcome them; the second is an emblematic example of a situation in which the intervention being evaluated is clearly not the main driver of the expected changes; the third gives an example of the use of contribution analysis in private sector development:

Delahais, Thomas. and Toulemonde, Jacques. 2012. Applying Contribution Analysis: Lessons from Five Years of Practice. Evaluation, 18(3): 281‑93. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356389012450810

Delahais, Thomas, and Toulemonde, Jacques. 2017. Making Rigorous Causal Claims in a Real-Life Context: Has Research Contributed to Sustainable Forest Management?. Evaluation, 23(4): 370‑88. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356389017733211

Ton, Giel. 2021. Development Policy and Impact Evaluation: Learning and Accountability in Private Sector Development. In Handbook of Development Policy by Zafarullah, Habib. and Huque, Ahmed. 378‑90. Edward Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781839100871.00042