MIXED METHODS AND CROSS-CUTTING APPROACHES

20 Theory-based Evaluation

Agathe Devaux-Spatarakis

Abstract

Theory-based evaluation was developed in response to the limitations of experimental and quasi-experimental approaches, which do not capture the mechanisms by which an intervention produces its impacts. This approach consists of opening the “black box” of public policy by breaking down the different stages of the causal chain linking the intervention to its final impacts. The hypotheses thus formulated on the mechanisms at play can then be tested empirically.

Keywords: Qualitative methods, theory, causal chain, intervention logic, theory of change, impact pathway

I. What does this approach consist of?

Formalised in the 1970s and 1980s in the United States, theory-based evaluation (TBE) is not a method, but rather a logic of evaluative research, an analytical approach that can mobilise several evaluation methods or tools. The term “theory” is to be understood here as the decomposition and explanation of a causal chain linking the public intervention to its expected results and impacts on the targeted and beneficiary publics. This takes the form of a graphic representation which then becomes the “scaffolding” underlying the evaluation investigations. Depending on its use, this tool may be called an “intervention logic”, “theory of change” or “impact pathway”. This approach is widely used in evaluation practice, although it covers a diversity of practices of varying quality and using more or less rigorous approaches.

Theory-based evaluation, contrary to what this name might suggest, seeks to be as close as possible to the reality on the ground and the context of the intervention. The term theory takes on a more or less scientific meaning depending on usage. At the very least, a theory-based approach is concerned with the theory of implementation of an intervention, i.e. the actions that are put in place for the proper implementation of the intervention in order to achieve the first results (intervention logic). In most cases, it tends to go a step further and make explicit the hypothetical causal links between an intervention and its intended outcomes up to and including final impacts (theory of change). This analysis is generally structured in several categories:

- Outputs represent the implementation of actions by public authorities,

- The results are the first immediate effects, directly linked to the achievements and which can be observed on the public participating in the actions,

- Intermediate and final impacts describe the expected impacts of the outputs on the final beneficiaries whose situation is to be improved.

This process systematically begins with the development of the ‘theory’. This is generally based on a literature review and discussions with the stakeholders of the intervention in order to identify the key components of the intervention, the target audiences, the main expected results and the final impacts targeted by the intervention. The theory is thus often co-constructed between evaluation teams and stakeholders and presents the main steps from outputs to final outcomes and impacts by connecting them and making explicit the assumptions for moving from one step to another. These hypotheses can cover the conditions for success, the risks linked to the context, but also, in the framework of a realist evaluation, the psycho-social mechanisms at work or, in the framework of a contribution analysis, specify the intervention’s contribution hypotheses. At this stage, the work can be consolidated by an analysis of the literature and thus a mobilisation of academic theories to support certain causal links (for example, in an intervention targeting a return to employment, drawing on what the scientific literature says about the causal relationship between a level of training and employment).

This theory becomes the scaffolding for the evaluation. Two types of empirical investigation are then conducted:

- Firstly, an analysis of change: are the steps identified or desired when the theory was conceived verified in the field? For whom and in what contexts?

- Then a causal analysis: How can we explain the passage or not of one stage to another? To what extent does the intervention contribute to generating these results? Under what conditions ? What psychosociological mechanisms can explain it?

The evaluation questions are therefore structured around theory testing and explanation. In this task, the evaluation team can mobilise a variety of evaluation methods or tools. For example, quantitative methods for estimating outcomes or impacts can be used, and these can be combined with qualitative methods to deepen the causal analysis.

Ultimately, the results of this approach take the form of a new ‘tested’ theory of the intervention showing the causal processes actually at work, those that do not work as expected and explaining the reasons why. This type of result then makes it possible to identify at which stage, in which context and with which audiences the intervention encountered difficulties and to propose operational and strategic improvements for future programming.

II. How is this approach useful for policy evaluation?

Mobilising a theory of change in an evaluation can serve different purposes. Breaking down the stages and causal links allows investigations to identify which stages are functional in the theory and which are more problematic. A public intervention is never a complete failure or success. For example, if it is found that the intervention did not achieve the desired results, the theory of change help identify whether the difficulties are related to implementation problems (actions that were not properly organised or difficulty in mobilising the target audiences) or to the capacity of the intervention to have the desired effects (actions were well organised and reached the target audiences, but failed to generate the desired effects on all or certain categories of audience). It is then possible to deepen the analysis of causality to try to understand whether these difficulties are linked to the programme itself or to external contextual elements that were not sufficiently taken into account during the design or implementation of the programme (competition with other policies, constraints that hindered the participation of the public, insufficient analysis of needs, or changes in the economic situation, for example).

This approach can be used to answer questions such as: “Where did intervention Y contribute to generating outcome X and why?” More generally, it can be used to answer all types of evaluative questions on effectiveness, impact, relevance, internal or external coherence and efficiency. Since each of these areas can be investigated to explain success or failure in moving from one stage of the theory to another.

It can be used at the design stage of an intervention to bring together stakeholders, co-construct the theory and anticipate risks before implementation, and modify programming to increase the chances of success. In this case, it is also useful for the appropriation of a common and shared vision of the intervention by the stakeholders.

It is also particularly relevant in in itinere evaluations (conducted as the intervention unfolds) in order to verify during the implementation, the achievement of the different stages and to adjust the implementation accordingly. Finally, in the case of an ex-post evaluation, it allows for a comparison between the initial theory and the theory as reformulated as a result of the empirical investigation phase of the evaluation, and to understand the reasons for their differences.

III. An example of the use of this approach in the evaluation of a nutritional programme

Theory-based evaluation approaches are mobilised in a variety of contexts and are equally suited to simple projects and complex public policies. An example of its use in a simple project can briefly illustrate the added value of this approach.

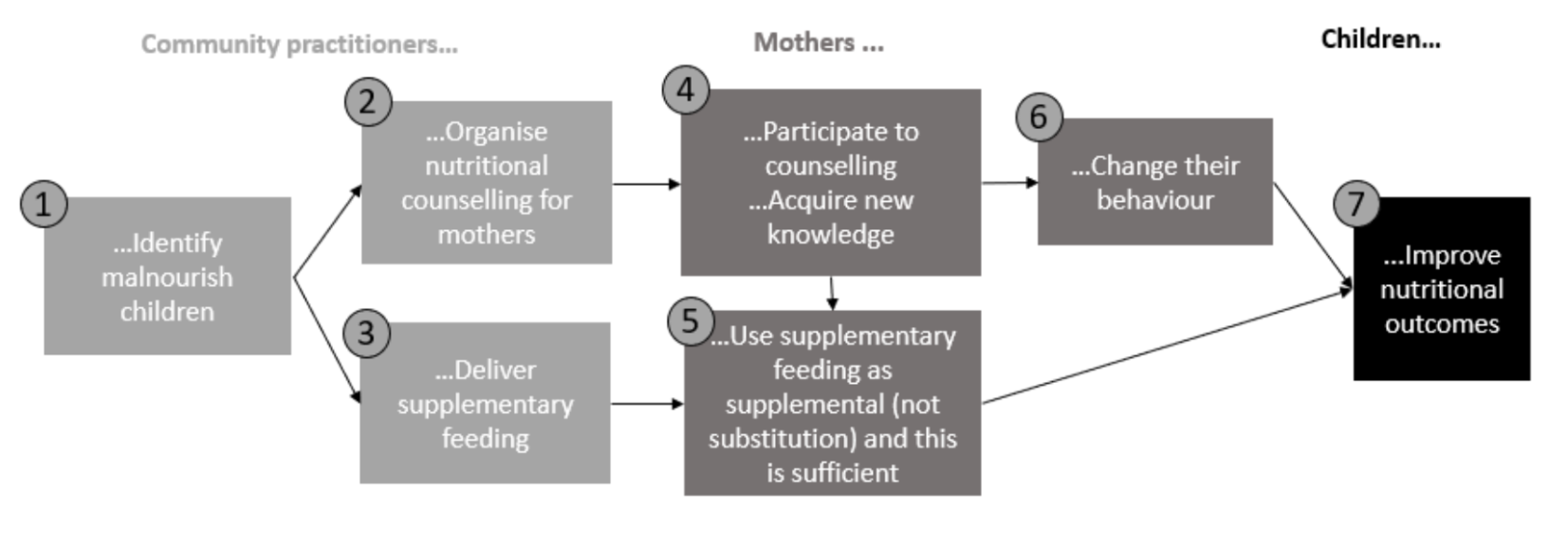

In a paper for the International Initiative for Impact Evaluation, Howard White (2009) presents the case of the Bangladesh Integrated Nutrition Project (BINP) evaluation. This project identifies malnourished children and provides supplementary feeding and nutrition counselling to the mothers of these children. The ultimate goal is to increase the growth of the children.

An initial comparison group evaluation by propensity score matching found no impact of the project on the nutritional status of children, but a positive impact only on the most malnourished children. However, this result by itself does not provide any lessons on how the project is not working or what can be done to improve it.

A complementary theory-based evaluation has enriched these results and proposed orientations for action. This approach focused first on reconstructing the theory of the project and then on clarifying and investigating the causal assumptions underlying the action.

A first step is the correct identification of malnourished children (1). This step is based on the assumption that parents bring their children to the prevention centres and that malnourished children are well identified. Here it seems that the programme was able to reach the target audience (90% of eligible women brought their children), nevertheless the selection of children by community practitioners showed several type 1 errors (malnourished children not selected) and type 2 errors (children selected when they are not malnourished).

The 2-4-6-7 causal chain is based on the assumption that the right target audiences have been identified and that the modes of action are relevant. However, an anthropological study and focus groups revealed that the mothers targeted by this public policy device had little influence on their child’s nutrition, as the men were responsible for food shopping and most mothers-in-law were in charge of preparing meals. Thus, although they participated in the training, and learned new knowledge, the mothers were only in a position to apply it when they became mothers-in-law in turn.

The 3-5-7 causal chain is based on the assumption that malnourished children were indeed selected, and that the food supplement is used as a complement and not as a substitute or shared among the children and that it is sufficient to improve the nutritional outcomes of the effects. However, the surveys conducted showed that these two assumptions were not verified in many cases.

This evaluation identified very operational recommendations to improve the effects of the project, including the participation of mothers-in-law and husbands in nutrition counselling sessions, as well as better training of community practitioners in charge of selecting children and targeting the most malnourished children.

IV. What are the criteria for judging the quality of the mobilisation of this approach?

The quality of the mobilisation of this approach can be analysed at two points in the evaluation.

First, the theory development phase should result in the most plausible theory before the field investigation. Ideally, a good theory is co-constructed between the evaluation team and the different stakeholders and also mobilises external knowledge that can inform the plausibility of the hypotheses of causal links between the different stages of this theory. Plausibility means that it reflects a reasonable ambition for the intervention in terms of the changes it is likely to generate. Finally, a good theory is synthetic, simple to understand and clearly indicates through a graphical representation who is acting and who is likely to change their behaviour or see their situation improve as a result of the intervention.

Secondly, the quality criteria for the theory-testing phase are in line with the general standards of data collection and analysis. Collection tools should be diversified to reflect a plurality of data sources (quantitative and qualitative) and points of view in order to consolidate the results as much as possible. Data collection and analysis are ideally conducted in an iterative manner (in successive phases) in order to refine the theory of change and its assumptions throughout the evaluation.

The results of the evaluation should then be presented in terms of testing the theory and showing what worked and what did not work for which audiences, why and under what conditions.

V. What are the strengths and limitations of this approach compared to others?

The main advantage of this approach is to ‘open the black box’ of public policy. Unlike experimental or quasi-experimental approaches, which make it possible to identify impacts without analysing how these were produced, theory-based evaluation makes it possible to identify and break down the mechanisms leading to the production of the impact. To do this, it applies an analytical approach that breaks down the intervention into stages and causal links and distinguishes between what is contextual and what is interventional. Explaining the assumptions underlying the action requires the evaluation team to look at the contexts of implementation, the characteristics of the audiences and the “bets” of the intervention, i.e. how it is likely to be a lever for change. The evaluation results are therefore particularly contextualised and generate lessons even when the intervention is not finalised, since each stage of implementation can be investigated.

However, this approach can be destabilising, as unlike other methods, there is not one distinct way and protocol to be followed in implementing it. Thus, many evaluation practitioners may claim to be part of this approach without meeting the quality standards of this exercise.

Furthermore, this method has been criticised for paying too much attention to the analysis of the expected theory and for obscuring the identification of alternative explanations for the observed processes or unanticipated results. This is indeed a pitfall to which the evaluation team must be attentive by attempting both in the design of the theory and in its testing to be open to the formulation and identification of such alternative explanations and identification of unexpected impacts. The use of the contribution analysis method makes it possible to focus the analysis on the role of the intervention in a more complex causal package and to investigate alternative explanations.

Some bibliographical references to go further

Birckmayer, Johanna D.. and Weiss, Carol H.. 2000. “Theory-Based Evaluation in Practice, What Do We Learn?” Evaluation Review, 24(4): 407-431.

Funnell, Sue. and Rogers, Patricia. 2011. Purposeful Program Theory. Effective use of Theories of Change and Logic Models. Jossey-Bass, Chichester.

Rogers, Patricia. and Petrosino, Anthony. et al.. 2000. “Program Theory Evaluation: Practice, Promise, and Problems.” New directions for evaluation, 87: 5-13.

Van Es, Marjan. and Guijt, Irene. and Vogel, Isabel. 2015. Theory of change thinking in practice: A stepwise approach, Hivos ToC Guidelines, Hivos people unlimited.

Weiss, Carol. 1997. “Theory-based Evaluation: Past, Present, and Future.” New directions for evaluation, 76: 41-55.

White, Howard. 2009. “Theory-Based Impact Evaluation: Principles and Practice.” Working paper 3, International initiative for Impact Evaluation.