Introduction

This publication follows a first book (Évaluation : fondements, controverses, perspectives) published at the end of 2021 by Editions Science et Bien Commun (ESBC) with the support of the Laboratory for interdisciplinary evaluation of public policies (LIEPP), compiling a series of excerpts from fundamental and contemporary texts in evaluation (Delahais et al. 2021). Although part of this book is dedicated to the diversity of paradigmatic approaches, we chose not to go into a detailed presentation of methods on the grounds that this would at least merit a book of its own. This is the purpose of this volume. This publication is part of LIEPP’s collective project in two ways: through the articulation between research and evaluation, and through the dialogue between quantitative and qualitative methods.

Methods between research and evaluation

Most definitions of programme evaluation[1] articulate three dimensions, described by Alkin and Christie as the three branches of the “evaluation theory tree” (Alkin and Christie 2012). These are the mobilisation of research methods (evaluation is based on systematic empirical investigation), the role of values in providing criteria for judging the intervention under study, and the focus on the usefulness of the evaluation.

The use of systematic methods of empirical investigation is therefore one of the foundations of evaluation practice. This is how evaluation in the sense of evaluative research differs from the mere subjective judgement that the term ‘evaluation’ in its common sense may otherwise denote (Suchman 1967). Evaluation is first and foremost an applied research practice, and as such, it has borrowed a whole series of investigative techniques, both quantitative and qualitative, initially developed in basic research (e.g. questionnaires, quantitative analyses on databases, experimental methods, semi-structured interviews, observations, case studies, etc.). Beyond the techniques, the borrowing also concerns the methods of analysis and the conception of research designs. Despite this strong methodological link, evaluation does not boil down to a research practice (Wanzer 2021).This is suggested by the other two dimensions identified earlier (the concern for values and utility). In fact, the development of programme evaluation has given rise to a plurality of practices by a variety of public and private actors (public administration, consultants, NGOs, etc.), practices within which methodological issues are not necessarily central and where methodological rigour greatly varies.

At the same time, the practice of evaluation has remained weakly and very unevenly institutionalised in the university (Cox 1990), where it suffers in particular from a frequent devaluation of applied research practices, suspicions of complacency towards commissioners, and difficulties linked to its interdisciplinary nature (see below) (Jacob 2008). Thus, although it has developed its journals and professional conferences, evaluation is still the subject of very few doctoral programmes and dedicated recruitments. Practised to varying degrees by different academic disciplines (public health, economics and development are now particularly involved), and sometimes described as ‘transdisciplinary’ in terms of its epistemological scope (Scriven 1993), evaluation is still far from being an academic discipline in the institutional sense of the term. From an epistemological point of view, this non- (or weak) disciplinarisation of evaluation is to be welcomed. The fact remains, however, that this leads to weaknesses. One of the consequences of this situation is a frequent lack of training for researchers in evaluation: particularly concerning the non-methodological dimensions of this practice (questions of values and utility), but also concerning certain approaches more specifically derived from evaluation practice.

Indeed, while evaluation has largely borrowed from social science methods, it has also fostered a number of methodological innovations. For example, the use of experimental methods first took off in the social sciences in the context of evaluation, initially in education in the 1920s and then in social policy, health and other fields from the 1960s onwards (Campbell and Stanley 1963). The link with medicine brought about by the borrowing of the model of the clinical trial (the notions of ‘trial’ and ‘treatment’ having thus been transposed to evaluation) then favoured the transfer from the medical sciences to evaluation of another method, systematic literature reviews, which consists in adopting a systematic protocol to search for existing publications on (a) given evaluative question(s) and to draw up a synthesis of their contributions (Hong and Pluye 2018; Belaid and Ridde 2020). Without being the only place where it is deployed, programme evaluation has also made a major contribution to the development and theorising of mixed methods, which consist of articulating qualitative and quantitative techniques in the same research (Baïz and Revillard 2022; Greene, Benjamin and Goodyear 2001; Burch and Heinrich 2016; Mertens 2017). Similarly, because of its central concern with the use of knowledge, evaluation has been a privileged site for the development of participatory research and its theorisation (Brisolara 1998; Cousins and Whitmore 1998; Patton 2018).

While these methods (experimental methods, systematic literature reviews, mixed methods, participatory research) are immediately applicable to fields other than programme evaluation, other methodological approaches and tools have been more specifically developed for this purpose[2]. This is particularly the case of theory-based evaluation (Weiss 1997; Rogers and Weiss 2007), encompassing a variety of approaches (realist evaluation, contribution analysis, outcome harvesting, etc.) which will be described below (Pawson and Tilley 1997; Mayne 2012; Wilson-Grau 2018). Apart from a few disciplines in which they are more widespread, such as public health or development (Ridde and Dagenais 2009; Ridde et al. 2020), these approaches are still little known to researchers who have undergone traditional training in research methods, including those who may be involved in evaluation projects.

A dialogue therefore needs to be renewed between evaluation and research: according to the reciprocal dynamic of the initial borrowing of research methods by evaluation, a greater diversity of basic research circles would now benefit from a better knowledge of the specific methods and approaches derived from the practice of evaluation. This is one of the vocations of LIEPP, which promotes a strengthening of exchanges between researchers and evaluation practitioners. Since 2020, LIEPP has been organising a monthly seminar on evaluation methods and approaches (METHEVAL), alternating presentations by researchers and practitioners, and bringing together a diverse audience[3]. This is also one of the motivations behind the book Evaluation: Foundations, Controversies, Perspectives, published in 2021, which aimed in particular to make researchers aware of the non-methodological aspects of evaluation (Delahais et al. 2021). This publication completes the process by facilitating the appropriation of approaches developed in evaluation such as theory-based evaluation, realistic evaluation, contribution analysis and outcome harvesting.

Conversely, LIEPP believes that evaluation would benefit from being more open to methodological tools more frequently used in basic research and with which it tends to be less familiar, particularly because of the targeting of questions at the scale of the intervention. In fact, evaluation classically takes as its object an intervention or a programme, usually on a local, regional or national scale, and within a sufficiently targeted questioning perimeter to allow conclusions to be drawn regarding the consequences of the intervention under study. By talking about policy evaluation rather than programme evaluation in the strict sense, our aim is to include the possibility of reflection on a more macro scale in both the geographical and temporal sense, by integrating reflections on the historicity of public policies, on the arrangement of different interventions in a broader policy context (a welfare regime, for example), and by relying more systematically on international comparative approaches. Evaluation, in other words, must be connected to policy analysis – an ambition already stated in the 1990s by the promoters of an “évaluation à la française” (Duran, Monnier, and Smith 1995; Duran, Erhel, and Gautié 2018). This is made possible, for example, by comparative historical analysis and macro-level comparisons presented in this book. Another important implication of programme evaluation is that the focus is on the intervention under study. By shifting the focus, many basic research practices can provide very useful insights in a more prospective way, helping to understand the social problems targeted by the interventions. All the thematic research conducted in the social sciences provides very useful insights for evaluation in this respect (Rossi, Lipsey, and Freeman 2004). Among the methods presented in this book, experimental approaches such as laboratory experimentation or testing, which are not necessarily focused on interventions as such, help to illustrate this more prospective contribution of research to evaluation.

A dialogue between qualitative and quantitative approaches

By borrowing its methods from the social sciences, policy evaluation has also inherited the associated methodological and epistemological controversies. Although there are many calls for reconciliation, although evaluation is more likely to emphasise its methodological pragmatism (the evaluative question guides the choice of methods), and although it has been a driving force in the development of mixed methods, in practice, in evaluation as in research, the dialogue between quantitative and qualitative traditions (especially in their epistemological dimension) is not always simple.

Articulating different disciplinary and methodological approaches to evaluate public policies is the founding ambition of LIEPP. The difficulties of this dialogue, particularly on an epistemological level (opposition between positivism and constructivism), were identified at the creation of the laboratory (Wasmer and Musselin 2013). Over the years, LIEPP has worked to overcome these obstacles by organizing a more systematic dialogue between different methods and disciplines in order to enrich evaluation: through the development of six research groups co-led by researchers from different disciplines, through projects carried out by interdisciplinary teams, but also through the regular discussion of projects from one discipline or family of methods by specialists from other disciplines or methods. It is also through these exchanges that the need for didactic material to facilitate the understanding of quantitative methods by specialists in qualitative methods, and vice-versa, has emerged. This mutual understanding is becoming increasingly difficult in a context of growing technicisation of methods. This book responds to this need, drawing heavily on the group of researchers open to interdisciplinarity and to the dialogue between methods that has been built up at LIEPP over the years: among the 25 authors of this book, nine are affiliated to LIEPP and eight others have had the opportunity to present their research at seminars organised by LIEPP.

This book has therefore been conceived as a means of encouraging a dialogue between methods, both within LIEPP and beyond. The aim is not necessarily to promote the development of mixed-methods research, although the strengths of such approaches are described (Part III). It is first of all to promote mutual understanding between the different methodological approaches, to ensure that practitioners of qualitative methods understand the complementary contribution of quantitative methods, their scope and their limits, and vice versa. In doing so, the approach also aims to foster greater reflexivity in each methodological practice, through a greater awareness of what one method is best suited for and the issues for which other methods are more relevant. While avoiding excessive technicality, the aim is to get to the heart of how each method works in order to understand concretely what it allows and what it does not allow. We are betting that this practical approach will help to overcome certain obstacles to dialogue between methods linked to major epistemological oppositions (positivism versus constructivism, for example) which are not necessarily central in everyday research practice. For students and non-academic audiences (particularly among policymakers or NGOs who may have recourse to programme evaluations), the aim is also to promote a more global understanding of the contributions and limitations of the various methods.

Far from claiming to be exhaustive, the book aims to present some examples of three main families of methods or approaches: quantitative methods, qualitative methods, and mixed methods and cross-sectional approaches in evaluation[4]. In what follows, we present the general organisation of the book and the different chapters, integrating them into a more global reflection on the distinction between quantitative and qualitative approaches.

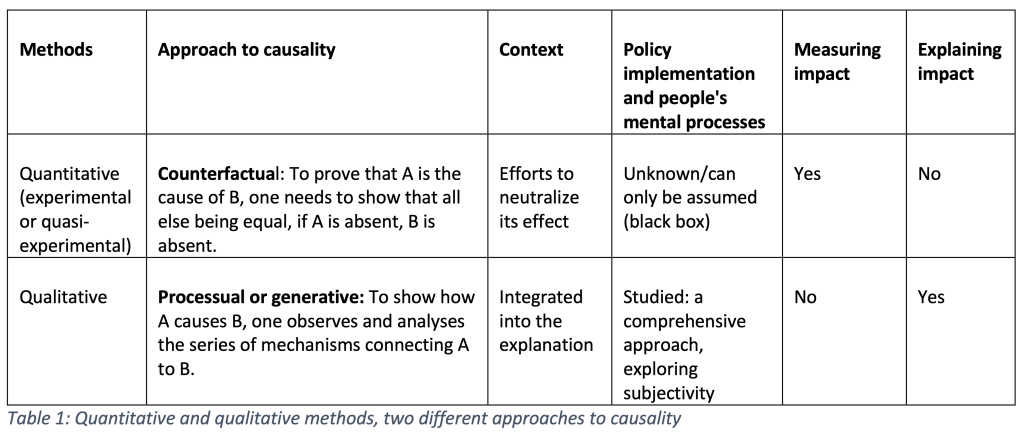

At a very general level, quantitative and qualitative methods are distinguished by the density and breadth of the type of information they produce: whereas quantitative methods can produce limited information on a large number of cases, qualitative methods provide denser, contextualised information on a limited number of cases. But beyond these descriptive characteristics, the two families of methods also tend to differ in their conception of causality. This is a central issue for policy evaluation which, without being restricted to this question[5], was founded on investigating the impact of public interventions: to what extent can a given change observed be attributed to the effect of a given intervention? – In other words, a causal question (can a cause-and-effect relationship be established between the intervention and the observed change?). To understand the complementary contributions of quantitative and qualitative methods for evaluation, it is therefore important to understand the different ways in which they tend to address this central question of causality.

Quantitative methods

Experimental and quasi-experimental quantitative methods are based on a counterfactual view of causality: to prove that A causes B, it must be shown that, all other things being equal, if A is absent, B is absent (Woodward 2003). Applied to the evaluation of policy impact, this logic invites us to prove that an intervention causes a given impact by showing that in the absence of this intervention, all other things being equal, this impact does not occur (Desplatz and Ferracci 2017). The whole difficulty then consists of approximating as best as possible these ‘all other things being equal’ situations: what would have happened in the absence of the intervention, all other characteristics of the situation being identical? It is this desire to compare situations with and without intervention ‘all other things being equal’ that gave rise to the development of experimental methods in evaluation (Campbell and Stanley 1963; Rossi, Lipsey, and Freeman 2004).

Most experiments conducted in policy evaluation are field experiments, in the sense that they study the intervention in situation, as it is actually implemented. Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) (see Chapter 1) compare an experimental group (receiving the intervention) with a control group, aiming for equivalence of characteristics between the two groups by randomly assigning participants to one or the other group. This type of approach is particularly well suited to interventions that are otherwise referred to as ‘experiments’ in public policy (Devaux-Spatarakis 2014). These are interventions that public authorities launch in a limited number of territories or organisations to test their effects[6], thus allowing for the possibility of control groups. When this type of direct experimentation is not possible, evaluators can resort to several quasi-experimental methods, aiming to reconstitute comparison groups from already existing situations and data (thus without manipulating reality, unlike experimental protocols) (Fougère and Jacquemet 2019). The difference-in-differences method uses a time marker at which one of the two groups studied receives the intervention and the other does not, and measures the impact of the intervention by comparing the results before and after this time (see Chapter 2). Discontinuity regression (see Chapter 3) reconstructs a target group and a control group by comparing the situations on either side of an eligibility threshold set by the policy under study (e.g. eligibility for the intervention at a given age, income threshold, etc.). Finally, matching methods (see Chapter 4) consist of comparing the situations of beneficiaries of an intervention with those of non-beneficiaries with the most similar characteristics.

In addition to these methods, which are based on real-life data, other quantitative impact assessment approaches are based on computer simulations or laboratory experiments. Microsimulation (see Chapter 5), the development of which has been facilitated by improvements in computing power, consists of estimating ex ante the expected impact of an intervention by taking into consideration a wide variety of data relating to the targeted individuals and simulating changes in their situation (e.g. ageing, changes in the labour market, fiscal policies, etc.). It also allows for a refined ex post analysis of the diversity of effects of a given policy on the targeted individuals. Policy evaluation can also rely on laboratory experiments (see Chapter 6), which make it possible to accurately measure the behaviour of individuals and, in particular, to uncover unconscious biases. Such analyses can, for example, be very useful in helping to design anti-discrimination policies, as part of an ex ante evaluation process. It is also in the context of reflection on these policies that testing methods (see Chapter 7) have been developed, making it possible to measure discrimination by sending fictitious applications in response to real offers (for example, job offers). But evaluation also seeks to measure the efficiency of interventions, beyond their impact. This implies comparing the results obtained with the cost of the policy under study and with those of alternative policies, in a cost-efficiency analysis approach (see Chapter 8).

Qualitative methods

While they are also compatible with counterfactual approaches, qualitative methods are more likely to support a generative or processual conception of causality (Maxwell 2004; 2012; Mohr 1999). Following this logic, causality is inferred, not from relations between variables, but from the analysis of the processes through which it operates. While the counterfactual approach establishes whether A causes B, the processual approach shows how (through what series of mechanisms) A causes B, through observing the empirical manifestations of these causal mechanisms that link A and B. In so doing, it goes beyond the behaviourist logic which, in counterfactual approaches, conceives the intervention according to a stimulus-response mechanism, the intervention itself then constituting a form of black box. Qualitative approaches break down the intervention into a series of processes that contribute to producing (or preventing) the desired result: this is the general principle of theory-based evaluations (presented in the third part of this book in Chapter 20 as they are also compatible with quantitative methods). This finer scale analysis is made possible by focusing on a limited number of cases, which are then studied in greater depth using different qualitative techniques. Particular attention is paid to the contexts, as well as to the mental processes and the logic of action of the people involved in the intervention (agents responsible for its implementation, target groups), in a comprehensive approach (Revillard 2018). Unlike quantitative methods, qualitative methods cannot measure the impact of a public policy; they can, however, explain it (and its variations according to context), but also answer other evaluative questions such as the relevance or coherence of interventions. Table 1 summarises these ideal-typical differences between quantitative and qualitative methods: it is important to specify that we are highlighting here the affinities of a given family of methods with a given approach to causality and a given consideration of processes and context, but this is an ideal-typical distinction which is far from exhausting the actual combinations in terms of methods and research designs.

The most emblematic qualitative research technique is probably direct observation or ethnography, coming from anthropology, which consists of directly observing the social situation being studied in the field (see Chapter 9). A particularly engaging method, direct observation is very effective in uncovering all the intermediate policy processes that contribute to producing its effects, as well as in distancing official discourse through the direct observation of interactions. The semi-structured interview (see Chapter 10) is another widely used qualitative research technique, which consists of a verbal interaction solicited by the researcher with a research participant, based on a grid of questions used in a very flexible manner. The interview aims both to gather information and to understand the experience and worldview of the interviewee. This method can also be used in a more collective setting, in the form of focus groups (see Chapter 11) or group interviews (see Chapter 12). As Ana Manzano points out in her chapter on focus groups, the terminologies for these group interview practices vary. Our aim in publishing two chapters on these techniques is not to rigidify the distinction but to provide two complementary views on these frequently used methods.

Although case studies (see Chapter 13) can use a variety of qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods, they are classically part of a qualitative research tradition because of their connection to anthropology. They allow interventions to be studied in context and are particularly suited to the analysis of complex interventions. Several case studies can be combined in the evaluation of the same policy; the way in which they are selected is then decisive. Process tracing (see Chapter 14), which relies mainly but not exclusively on qualitative enquiry techniques, focuses on the course of the intervention in a particular case, seeking to trace how certain actions led to others. The evaluator then acts as a detective looking for the “fingerprints” left by the mechanisms of change. The approach makes it possible to establish under what conditions, how and why an intervention works in a particular case. Finally, comparative historical analysis combines the two fundamental methodological tools of social science, comparison and history, to help explain large-scale social phenomena (see Chapter 15). It is particularly useful for reporting on the definition of public policies.

Mixed methods and cross-cutting approaches in evaluation

The third and final part of the book brings together a series of chapters on the articulation between qualitative and quantitative methods as well as on cross-cutting approaches that are compatible with a diversity of methods. Policy evaluation has played a driving role in the formalisation of the use of mixed methods, leading in particular to the distinction between different strategies for linking qualitative and quantitative methods (sequential exploratory, sequential explanatory or convergent design) (see Chapter 16). Even when the empirical investigation mobilises only one type of method, it benefits from being based on a systematic mixed methods literature review. While the practice of systematic literature reviews was initially developed to synthesise results from randomised controlled trials, this practice has diversified over the years to include other types of research (Hong and Pluye 2018). The particularity of systematic mixed methods literature reviews is that they include quantitative, qualitative and mixed studies, making it possible to answer a wider range of evaluative questions (see Chapter 17).

Having set out this general framework on mixed methods and reviews, the following chapters present six cross-cutting approaches. The first two, macro-level comparisons and qualitative comparative analysis (QCA), tend to be drawn from basic research practices, while the other four (theory-based evaluation, realist evaluation, contribution analysis, outcome harvesting) are drawn from the field of evaluation. Macro-level comparisons (see Chapter 18) consist of exploiting variations and similarities between large entities of analysis (e.g. states or regions) for explanatory purposes: for example, to explain differences between large social policy models, or the influence of a particular family policy configuration on women’s employment rate. Qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) is a mixed method which consists in translating qualitative data into a numerical format in order to systematically analyse which configurations of factors produce a given result (see Chapter 19). Based on an alternative, configurational conception of causality, it is useful for understanding why the same policy may lead to certain changes in some circumstances and not in others.

Developed in response to the limitations of experimental and quasi-experimental approaches to understanding how an intervention produces its impacts, theory-based evaluation consists of opening the ‘black box’ of public policy by breaking down the different stages of the causal chain linking the intervention to its final results (see Chapter 20). The following chapters fall broadly within this family of evaluation approaches. Realist evaluation (see Chapter 21) conceives of public policies as interventions that produce their effects through mechanisms that are only triggered in specific contexts. By uncovering context-mechanism-outcomes (CMO) configurations, this approach makes it possible to establish for whom, how and under what circumstances an intervention works. Particularly suited to complex interventions, contribution analysis (see Chapter 22) involves the progressive formulation of ‘contribution claims’ in a process involving policy stakeholders, and then testing these claims systematically using a variety of methods. Outcome harveting (see Chapter 23) starts from a broad understanding of observable changes, and then traces whether and how the intervention may have played a role in producing them. Finally, the last chapter is devoted to an innovative approach to evaluation, based on the concept of cultural safety initially developed in nursing science (see Chapter 24). Cultural safety aims to ensure that the evaluation takes place in a ‘safe’ manner for stakeholders, and in particular for the minority communities targeted by the intervention under study, i.e. that the evaluation process avoids reproducing mechanisms of domination (aggression, denial of identity, etc.) linked to structural inequalities. To this end, various participatory techniques are used at all stages of the evaluation. This chapter is thus an opportunity to emphasise the importance of participatory dynamics in evaluation, also highlighted in several other contributions.

A didactic and illustrated presentation

To facilitate reading and comparison between methods and approaches, each chapter is organised according to a common outline based on five main questions:

1) What does this method/approach consist of?

2) How is it useful for policy evaluation?

3) An example of the use of this method/approach;

4) What are the criteria for judging the quality of the use of this method/approach?

5) What are the strengths and limitations of this method/approach compared to others?

The book is published directly in two languages (French and English) in order to facilitate its dissemination. The contributions were initially written in one or the other language according to the preference of the authors, then translated and revised (where possible) by them. A bilingual glossary is available below to facilitate the transition from one language to the other.

The examples used cover a wide range of public policy areas, studied in a variety of contexts: pensions in Italy, weather and climate information in Senegal, minimum wage in New Jersey, reception in public services in France, child development in China, the fight against smoking among young people in the United Kingdom, health financing in Burkina Faso, the impact of a summer school on academic success in the United States, soft skills training in Belgium, the development of citizen participation to improve public services in the Dominican Republic, a nutrition project in Bangladesh, universal health coverage in six African countries, etc. The many examples presented in the chapters illustrate the diversity and current vitality of evaluation research practices.

Far from claiming to be exhaustive, this publication is an initial summary of some of the most widely used methods. The collection is intended to be enriched by means of publications over time in the open access collection of LIEPP methods briefs[7].

Cited references

Alkin, Marvin. and Christie, Christina. 2012. ‘An Evaluation Theory Tree’. In Evaluation Roots, edited by Marvin Alkin and Christina Christie. London: Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412984157.n2.

Baïz, Adam. and Revillard, Anne. 2022. Comment Articuler Les Méthodes Qualitatives et Quantitatives Pour Évaluer L’impact Des Politiques Publiques? Paris: France Stratégie. https://www.strategie.gouv.fr/publications/articuler-methodes-qualitatives-quantitatives-evaluer-limpact-politiques-publiques.

Belaid, Loubna. and Ridde, Valéry. 2020. ‘Une Cartographie de Quelques Méthodes de Revues Systématiques’. Working Paper CEPED N°44.

Brisolara, Sharon. 1998. ‘The History of Participatory Evaluation and Current Debates in the Field’. New Directions for Evaluation, (80): 25–41. https://doi.org/10.1002/ev.1115.

Burch, Patricia. and Heinrich, Carolyn J.. 2016. Mixed Methods for Policy Research and Program Evaluation. Los Angeles: Sage.

Campbell, Donald T.. and Stanley, Julian C.. 1963. ‘Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs for Research’. In Handbook of Research on Teaching. Houghton Mifflin Company.

Cousins, J. Bradley. and Whitmore, Elizabeth. 1998. ‘Framing Participatory Evaluation’. New Directions for Evaluation, (80): 5–23.

Cox, Gary. 1990. ‘On the Demise of Academic Evaluation’. Evaluation and Program Planning, 13(4): 415–19.

Delahais, Thomas. 2022. ‘Le Choix Des Approches Évaluatives’. In L’évaluation En Contexte de Développement: Enjeux, Approches et Pratiques, edited by Linda Rey, Jean Serge Quesnel, and Vénétia Sauvain, 155–80. Montréal: JFP/ENAP.

Delahais, Thomas, Devaux-Spatarakis, Agathe, Revillard, Anne, and Ridde, Valéry. eds. 2021. Evaluation: Fondements, Controverses, Perspectives. Québec: Éditions science et bien commun. https://scienceetbiencommun.pressbooks.pub/evaluationanthologie/.

Desplatz, Rozenn. and Ferracci, Marc. 2017. Comment Évaluer l’impact Des Politiques Publiques? Un Guide à l’usage Des Décideurs et Praticiens. Paris: France Stratégie.

Devaux-Spatarakis, Agathe. 2014. ‘L’expérimentation “telle Qu’elle Se Fait”: Leçons de Trois Expérimentations Par Assignation Aléatoire’. Formation Emploi, (126): 17–38.

Duran, Patrice. and Erhel, Christine. and Gautié, Jérôme. 2018. ‘L’évaluation des politiques publiques’. Idées Économiques et Sociales, 193(3): 4–5.

Duran, Patrice. and Monnier, Eric. and Smith, Andy. 1995. ‘Evaluation à La Française: Towards a New Relationship between Social Science and Public Action’. Evaluation, 1(1): 45–63. https://doi.org/10.1177/135638909500100104.

Fougère, Denis. and Jacquemet, Nicolas. 2019. ‘Causal Inference and Impact Evaluation’. Economie et Statistique, (510-511–512): 181–200. https://doi.org/10.24187/ecostat.2019.510t.1996.

Greene, Jennifer C.. and Lehn, Benjamin. and Goodyear, Leslie. 2001. ‘The Merits of Mixing Methods in Evaluation’. Evaluation, 7(1): 25–44.

Hong, Quan Nha. and Pluye, Pierre. 2018. ‘Systematic Reviews: A Brief Historical Overview’. Education for Information, (34): 261–76.

Jacob, Steve. 2008. ‘Cross-Disciplinarization a New Talisman for Evaluation?’ American Journal of Evaluation 19(2): 175–94. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098214008316655.

Mathison, Sandra. 2005. Encyclopedia of Evaluation. London: Sage.

Maxwell, Joseph A. 2004. ‘Using Qualitative Methods for Causal Explanation’. Field Methods, 16(3): 243–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X04266831.

———. 2012. A Realist Approach for Qualitative Research. London: Sage.

Mayne, John. 2012. ‘Contribution Analysis: Coming of Age?’ Evaluation, 18(3): 270–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356389012451663.

Mertens, Donna M. 2017. Mixed Methods Design in Evaluation. Thousand Oaks: Sage. Evaluation in Practice Series. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781506330631.

Mohr, Lawrence B. 1999. ‘The Qualitative Method of Impact Analysis’. American Journal of Evaluation, 20(1): 69–84. https://doi.org/10.1177/109821409902000106.

Newcomer, Kathryn E.. and Hatry, Harry P.. and Wholey, Joseph S.. 2015. Handbook of Practical Program Evaluation. Hoboken: Wiley.

Patton, Michael Q. 1997. Utilization-Focused Evaluation. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

———. 2015. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods: Integrating Theory and Practice. London: Sage.

———. 2018. Utilization-Focused Evaluation. London: Sage.

Pawson, Ray. and Tilley, Nicholas. 1997. Realistic Evaluation. London: Sage.

Revillard, Anne. 2018. Quelle place pour les méthodes qualitatives dans l’évaluation des politiques publiques? Paris: LIEPP Working Paper n°81.

Ridde, Valéry. and Dagenais, Christian. 2009. Approches et Pratiques En Évaluation de Programme. Montréal: Presses de l’Université de Montréal.

Ridde, Valéry. and Dagenais, Christian (eds). 2020. Évaluation Des Interventions de Santé Mondiale: Méthodes Avancées. Québec: Éditions science et bien commun.

Rogers, Patricia J.. and Weiss, Carol H.. 2007. ‘Theory-Based Evaluation: Reflections Ten Years on: Theory-Based Evaluation: Past, Present, and Future’. New Directions for Evaluation, (114): 63–81. https://doi.org/10.1002/ev.225.

Rossi, Peter H.. and Mark W. Lipsey. and Howard E. Freeman. 2004. Evaluation: A Systematic Approach. London: Sage.

Scriven, Michael. 1993. ‘Hard-Won Lessons in Program Evaluation.’ New Directions for Program Evaluation, (58): 5–48.

Suchman, Edward A. 1967. Evaluative Research. Principles and Practice in Public Service and Social Action Programs. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Wanzer, Dana L. 2021. ‘What Is Evaluation? Perspectives of How Evaluation Differs (or Not) From Research’. American Journal of Evaluation, 42(1): 28–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098214020920710.

Wasmer, Etienne. and Musselin, Christine. 2013. Évaluation Des Politiques Publiques: Faut-Il de l’interdisciplinarité? Paris: LIEPP Methodological discussion paper n°2.

Weiss, Carol H. 1997. ‘Theory-Based Evaluation: Past, Present, and Future’. New Directions for Evaluation (76): 41–55. https://doi.org/10.1002/ev.1086.

———. 1998. Evaluation: Methods for Studying Programs and Policies. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Wilson-Grau, Ricardo. 2018. Outcome Harvesting: Principles, Steps, and Evaluation Applications. IAP.

Woodward, James. 2003. Making Things Happen a Theory of Causal Explanation. Oxford Studies in Philosophy of Science. New York: Oxford University Press.

- For example, Michael Patton's definition of evaluation as "the systematic collection of information about the activities, characteristics, and outcomes of programs to make judgements about the program, improve program effectiveness, and/or inform decisions about future programming" (Patton 1997, 23) ↵

- As opposed to methods in the sense of methodological tools, approaches are situated in "a kind of in-between between theory and practice" (Delahais 2022), by embodying certain paradigms. In evaluation, some may be very methodologically oriented, but others may be more concerned with values, with the use of results, or with social justice (ibid.). ↵

- The programme and resources from previous sessions of this seminar are available online: https://www.sciencespo.fr/liepp/fr/content/cycle-de-seminaires-methodes-et-approches-en-evaluation-metheval.html ↵

- In doing so, it complements other methodological resources available in handbooks (Ridde and Dagenais 2009; Ridde et al. 2020; Newcomer, Hatry, and Wholey 2015; Mathison 2005; Weiss 1998; Patton 2015) or online: for example the Methods excellence network (https://www.methodsnet.org/), or in the field of evaluation, the resources compiled by the OECD (https://www.oecd.org/fr/cad/evaluation/keydocuments.htm), the UN's Evalpartners network (https://evalpartners.org/), or in France the methodological guides of the Institut des politiques publiques (https://www.ipp.eu/publications/guides-methodologiques-ipp/) and the Société coopérative et participative (SCOP) Quadrant Conseil (https://www.quadrant-conseil.fr/ressources/evaluation-impact.php#/). ↵

- Evaluation also looks at, for example, the relevance, coherence, effectiveness, efficiency or sustainability of interventions. See OECD DAC Network on Development Evaluation (EvalNet) https://www.oecd.org/dac/evaluation/daccriteriaforevaluatingdevelopmentassistance.htm ↵

- Unfortunately, these government initiatives are far from being systematically and rigorously evaluated. ↵

- LIEPP Methods briefs : https://www.sciencespo.fr/liepp/en/publications.html#LIEPP%20methods%20briefs ↵