Introduction

Paul R. Carr, Eloy Rivas-Sánchez & Gina Thésée

The title of this book contains a multitude of concepts, word-games, conundrums, and images. Pygmalion originates from Greek mythology, and has spawned a number of constructions, such as the Pygmalion effect, complex, and myth. Often, in popular culture, this might apply to someone touting, boasting, uplifting and/or embellishing discourse so as to give the impression, or, more boldly, to literally affirm the supposed pure truth of a particular belief, even if all/most evidence is pointing in the other direction. Democracy is often associated with philosophical, ideological and belief systems, structures and operational models, elections and political parties as well as universal values such as liberty and freedom. It can be understood in thin/apolitical/uncritical or thick/engaged/critical ways, or in other ways, and it can also be viewed as an end-point or, on the contrary, a process.

If you build it, will they come is a re-formulated quote from the 1989 film Field of Dreams, adapted from Ray Kinsella’s book, and plays on the concept that if the main character were to build a baseball field, he would come, referring to the estranged relationship that the main character had with his father, and also connecting with an infamous baseball player from another epoch.

This book seeks to tie together the sensationalist cheerleading in some political circles, most notably in the United States, where it is quite common, expected and ruthlessly deceptive to create the illusion and to propagate it at every event through nationalist symbolism and rhetoric. The role-playing portends that a particular nation and people are (presumably) superior, better and logically more naturally blessed while discarding, downgrading and diminishing everyone else. Constantly repeating the mantra that, for example, and this is not the only case, the United States is the most advanced democracy, that it is a force of historical good, and that no other society has achieved the freedom and liberty that it has cultivated through its democracy is, or can be, a troubling and dangerous affirmation, a Pygmalion acrobatic act that requires all Presidents and political candidates to partake in the charade. There is no evidence to prove this belief but there are many indicators that this could not possibly be true. So why say it, and, more importantly, what are the costs and effects of maintaining such a posture?

As for democracy, elections are inscribed with anti-democratic etchings, social inequalities are rampant, the war industry prevents robust democratic action, constantly supporting dictatorships and oppression forces the system onto the low road, and the injection of capital and capitalism/neoliberalism makes serious efforts at transformative social change extremely difficult and problematic. Education has been forced into a neoliberal roller-coaster, and meaningful dialogue is often shut down in public spaces (Carr, Thésée & Rivas-Sanchez, 2023).

Thus, this book takes the stance that a steam-roller propaganda machine attempts to make people believe not only that there is no other option but, significantly, that everything is the best that it possibly can be. This is a debilitating form of normative democracy that is, at the very least, somewhat undemocratic. We do have elections (and normative democracy), something that “we,” supposedly, or “they” built, but it is not certain that “he” or “they” or “we” will come to the party. Or are “we” already there? Some scholars and writers argue that we are in a duopoly democracy with the two main parties dominating everything (Amy, 2020). Chomsky (2004, 2022) has critiqued USA democracy as not reflecting public interest, heavily dependent on elite forces, and on a hegemonic approach to developing an Empire intertwined with human rights problems[1]. There are also Marxist (Femia, 2003), Indigenous and colonial (Banerjee, 2022; Zembylas, 2022), feminist (Stopler, 2021) and anti-racist (Henry & Tator, 2009; López, 2021) critiques of normative democracy, including Henry Giroux’s (Giroux, 2018; Giroux & DiMaggio, 2024) strident critique of the USA model morphing into fascistic elements, imbued with White supremacy and an assault on critical education.

The inspiration for our UNESCO Chair in Democracy, Global Citizenship and Transformative Education is Paulo Freire (Thésée & Carr, 2020) and the many scholars and activists who have continued the work in pedagogy. The wonderful work of Peter McLaren and Antonia Darder, as well as Joe Kinchloe and Shirley Steinberg, and many others who have continued this fundamental work in carving a space for solidarity and agency when it looks as though normative democracy will crush human creativity and humanity (Steinberg & Down, 2020). Carr wrote his first book on democracy and critical pedagogy, entitled Does your vote count?, in 2010, and some fifteen years ago questioned how we could build a meaningful democracy through Freirian educational concepts and models. We’re still thinking and working on this project, and with Thésée (2019) they produced a book entitled “It’s not education that scares me, it’s the educators…”: Is there still hope for democracy in education, and education for democracy? that sought to synthesize their almost two-decade research-project on democracy and education.

This book argues that we need to build democracy rather than continuously bark out that we are the democratic ones, and that we have the right to impose our will on those who differ, through wars, excessive extractivism, forced migrations, environmental catastrophe and Panama Papers-style commercial dealings (O’Donovan et al., 2019). This construction of democracy requires dialogue and solidarity, openness and engagement, inclusiveness and power-sharing in non-hierarchical spaces, with decisions made by real people outside of winner-take-all elections. This book problematizes the media, education, war planning processes, social injustice and social movements, and we hope that we can collectively create (non-normative) democratic spaces together, involving civil society, marginalized sectors, the arts, educators, citizens and activists. And we also aspire to provide some nuance and contours to the transformative potential of anti-hegemonic democracy as a counterweight to Pygmalion democracy.

This volume contains more than a dozen chapters from colleagues in eight countries, together focused on problematizing the state of democracy today, and seeking diverse contours and shapes of what we are calling Pygmalion democracy. We are hoping that, throughout our efforts, analysis and contextualization of normative democracy, we can contribute, however humbly, to the construction of a more meaningful, solidarity- and social justice-based democracy. Importantly, while the USA casts a broad shadow over our project, our intention is not to retry uniquely the model, manifestation and realities produced by the country most affiliated with (normative) democracy. However, the 2024 USA presidential election cannot be overlooked or underplayed, and our readings and understandings of democracy, at some level, are cajoled, shaped and influenced by the polarized and polarizing horse-race that took place over the course of several years, culminating in the return of Donald Trump, despite everything, at the helm.

We are also beholden to Antonia Darder and Peter McLaren, who have provided, respectively, the foreword and afterword, tying everything together with their insightful and provocative analysis. For the rest of this chapter, we continue to develop the conceptual and theoretical framework of Pygmalion democracy.

Who says that “We’re the greatest”?

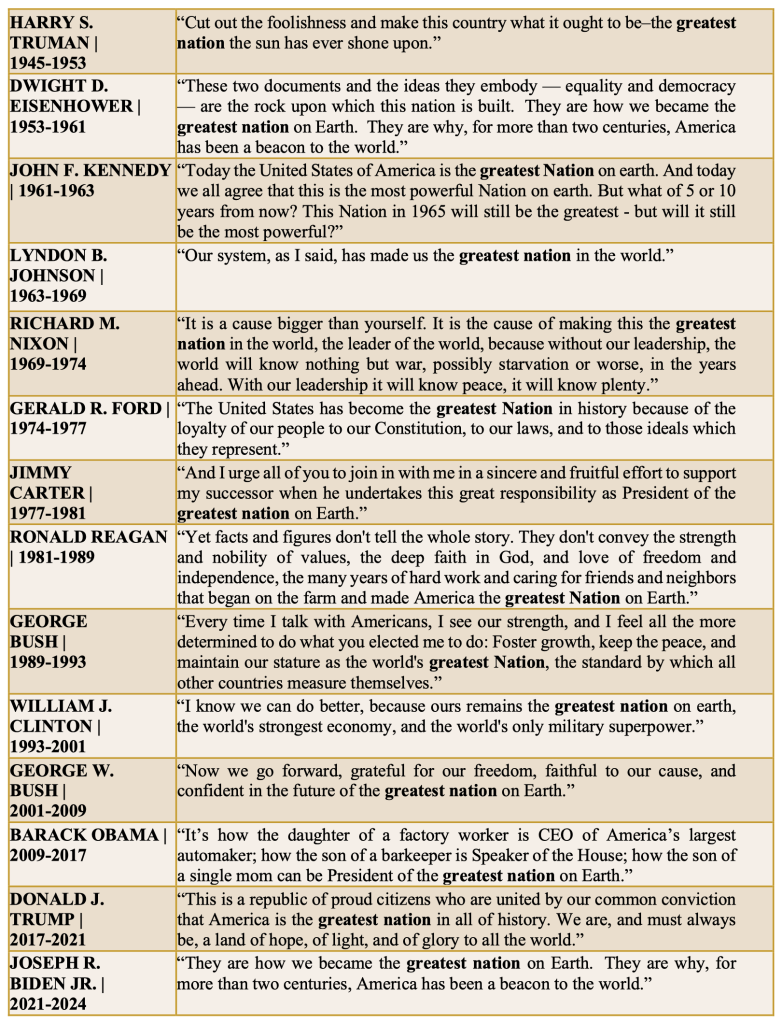

As Carr outlines in the first chapter, the USA plays a larger-than-life billboard hyper-representation of a domineering super-power, and Empire, and the pretension of being the “Voice of the Free World”. The USA has been extremely effective in portraying itself as the most democratic country on Earth, a country unlike others in ingratiating itself with supposed superior values and virtues. Table I.1 presents pronouncements by USA presidents from the 1940s until today. Regardless of Democratic or Republican party affiliation, there is a clear, unshakable, tightly-tethered and consistent discourse throughout, that the USA is the world’s “greatest” nation and democracy.

All nation-states exhibit some pride in their accomplishments, in their constitutions, in their cultures and in their contributions to the world. In outright dictatorships, it would be entirely normal to have an extremely uncritical and visceral embrace of everything that originates in and from the discourse of its leaders. In democracies, there is the general belief that free speech, freedom of assembly and a free press will ensure that the nation-state will not be overrun by propaganda and narrow interpretations of who we are. Some might argue that the boosterism or jingoism or cheerleading that underpins these declarations of supposed moral superiority are meant to uplift, and not to misrepresent reality. What harm could there be in encouraging people to strive to be better? We do it in sports all the time, don’t we? We tell ourselves that we can beat or defeat the other team, not knowing whether we can or cannot do. We tell our children that they can be anything, hoping to encourage and inspire them not to lose hope. So why not shower the populace with the notion that “we” are better than everyone else.

Should there be a concern that every USA president for the past eighty years—and we didn’t go beyond that, but believe that this should be a consistent mantra throughout all of the presidents, starting with George Washington in 1789—states unequivocally that the USA is the “greatest”? Could it harm the nation, the society, the psyche of citizens and all people around the world? Is the intention to supplant reality, to cultivate delusions of grandeur, to ensure that discrimination and ignorance will be ingrained, to diminish meaningful relations with others or some other reason?

The hegemony that goes along with the incessant reminders, echoed generally by all major candidates and leaders in the USA, meshes with this vision of Empire. The unquestioned “greatness” and seemingly obvious designation by higher powers of a nation unlike all others flies in the face of reality. The first chapter of this book provides a comparative analysis of several nation-states with the USA, and concludes that the USA is facing severe challenges and difficulties in many areas associated with democracy, notably in terms of social justice, crime, the environment, freedom of speech, elections and in other areas. The point emphasized in that analysis is that there is no one “greatest” nation; all countries face issues, problems and inequalities. The danger is in believing that one nation is the “greatest” because that can lead to a massive internalization of false beliefs, a false conscientization in the Marxist sense.

What is “American exceptionalism,” where does it come from, and why is it sustained (Ceaser, 2012; Raine, 2024)? Early in the European colonization of what is now known as the USA, a mythology of greatness (“manifest destiny”), of enlightenment and a connection to religious and moral superiority reigned over the colonizers. This conflict, paradox and cognitive dissonance in the face of a massive genocide of the First Nations, those who resided, cultivated and attached themselves to the land and territory for thousands of years, could appear today as surreal and delusional. How could stealing the land of the Indigenous Peoples be pre-ordained or receive the benediction of the leading Christian religious institutions of the time? The Catholic Church promoted the Doctrine of Discovery, which provided explicit and tacit support, carriage and consent to colonize Indigenous Peoples and lands (see Jeff Share’s chapter in this book). The immigrants arriving in the USA in the 1600s were fleeing European injustice, thus laying the groundwork for glorious liberties and manifestations in the New World. Alexis de Tocqueville (2002), in 1835, in his classic work Democracy in America, emphasized the ‘exceptional’ character of the American people compared to the European monarchies and aristocracies of the day. Again, this took place during a time of slavery and rampant class, gender and other inequalities. We understand the context, constraints and culture of the period, and acknowledge that life was not easy anywhere during that period but we are also concerned about a sustained narrative based on that period.

A common belief in the USA is related to a strong mythological tradition, an American creed that presents itself as a society full of liberties, equality and opportunities that can lead to achieving the “American dream”. The realization of a fulfilled and wealthy life built on the mythology of individual effort, dedication and merit was considered uniquely an American phenomenon. In contemporary times, the notion of exceptionalism is based on the belief that the USA has a special role bestowed upon it by higher powers above all other nations, derived from its history, its political system, its democratic values, and so on. Is it helpful to maintain the notion of exceptionalism? Does it lead to unwarranted and deleterious nationalism, patriotism, notions of moral superiority over the world, xenophobia and other derivatives? If the USA is naturally better and superior to all other nations, what is the proof? Have other nations also not contributed to world humanity? The point is simply that there is no one nation superior to all others, and instilling this false belief can lead to much harm.

How can we reconcile racism, sexism, poverty, corruption, endless warfare that affects the working class more directly, nebulous power dynamics and lived experiences that offer minimal hope for social transformation and emancipation? Does this inculcation of the superiority complex of being better than all nations lead to a belittling and conscious ignorance of what others are, can be or will be? Cutting yourself off from the world under false pretenses, exemplified through the willful exemption from environmental accords, institutions of the United Nations, such as UNESCO, the International Criminal Court, and many other agreements, places the USA in an unusual position of being supposedly the “greatest” but not engaging with the world at many levels. Similarly, as is the case throughout the Americas, the USA ratified around 370 treaties (not always voluntarily) with Indigenous Nations (United States Government, 2022), which it often did not respect (United States Government, 2022; Pruitt, 2023) (and Canada and many other countries also fall into the category).

This background simply attempts to substantiate that the formulation by elites and political leaders and others concerned with sustained hegemony does not benefit the working class, marginalized groups, and people spread throughout society. What could be the benefit of believing that you are somehow superior to others, and then realizing, if the doors are open for that realization, that you have more in common with others than you were led to believe? Moreover, what might happen when you understand that you can learn from others, and that you need to be with others for your own self-preservation, for peace, for solidarity, for mutual socio-economic benefits, for environmental survival and for many other human and humane reasons?

Ultimately, we maintain that this illusion of “greatness” underlays the very fabric of democracy. Is it possible to be democratic if everyone must keep parroting that “we are the greatest,” paradoxically followed by a litany of evidence, facts, illustrations and realities that most definitely paint a portrait of a nation in and on hard times? Does the repetition of this national patriotic game inhibit the call, for example, for peace, or in engaging with the world to more fully and completely address climate catastrophe? Does it limit the travelling of USA citizens abroad (who have a relatively low level of international travel and also of passport obtention)? Does it limit cross-cultural, intercultural and interracial relations? Does it limit the quest for peace more so than the desire or the preparation for conflict? Importantly, does the nation-state represent accurately, fully and legitimately the people harboured within its borders?

A few side-notes framing the (sur)reality of Pygmalion democracy

There are a multitude of concerns and issues that could be injected into the framing of Pygmalion democracy, and the chapters in the book, collectively, provide the planks of the flooring to construct the building. We would like to highlight here two pivotal considerations, related to massive financial avarice and control and, despite that, significant solidarity and generosity among broad sections of the population. Before we do so, we would like to briefly comment on the state of the world today, and how we need a real, transformative, critically-engaged democracy to combat the man-made problems we see decimating human and non-human life and environments.

How should we think about democracy within nation-states and broader international systems that value, condone and ingratiate massive wealth accumulation? The degree of how far it can go varies, and, in many cases, is infinite. The effect on the vast majority of people is palpably debilitating, as witnessed through the eyes of those in poverty and facing extreme vulnerability. Do a few individuals effortlessly climb through the ranks to merit the enormous sums they accumulate, in addition to the status and power that they accrue?

Several of the chapters in this book examine the intricacies of formal power structures and normative democracy sustaining poverty. The normative discourse, through Pygmalion democracy, is that electors and neoliberal economics will level the playing field, allowing people to enjoy a comfortable “middle-class” life-style. Part of the Pygmalion discourse in the USA is that there is no working class, only a middle-class that seemingly includes just about everyone except a few elite elements. Yet, social mobility seems to be more muted than the mythology that seeks to include all social actors within a supposedly vibrant, functioning and socially just system (Smith et al., 2022).

Perhaps one of the most obvious, shocking and under-played variables in this debate about everyone contributing and “paying their fair share” is the reporting on the Panama Papers (Henry, 2016) in 2016 and the Pandora Papers (Guardian investigation team, 2021) in 2021. Together, the uncovering of millions of documents by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) revealed that tens of thousands of companies and hundreds of some of the wealthiest people on Earth are hiding their fortunes in off-shore tax-shelters, specifically to avoid paying tax in their home-countries (International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, 2017, 2021). It is almost mind-bending to think that working people must pay a significant percentage of their wages, salaries and earnings to contribute to building the society in which they live but the wealthiest need not make a contribution. These tax-havens are not only not officially legal; they seem to be a kind of a parlour game for the rich and famous so as to not have to support the masses in their own countries. The value of untaxed assets hidden in and through these Panamanian banking networks is estimated to be between $11 and $32 Trillion (in USA dollars), an astronomical amount that, if taxed, could surely assist in providing public services, notably education and health care, back home. Thanks to the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, some of the funds have been recovered (McGoey, 2021), and the exposé of the Panama and the Pandora Papers has made the international finance industry a little more transparent.

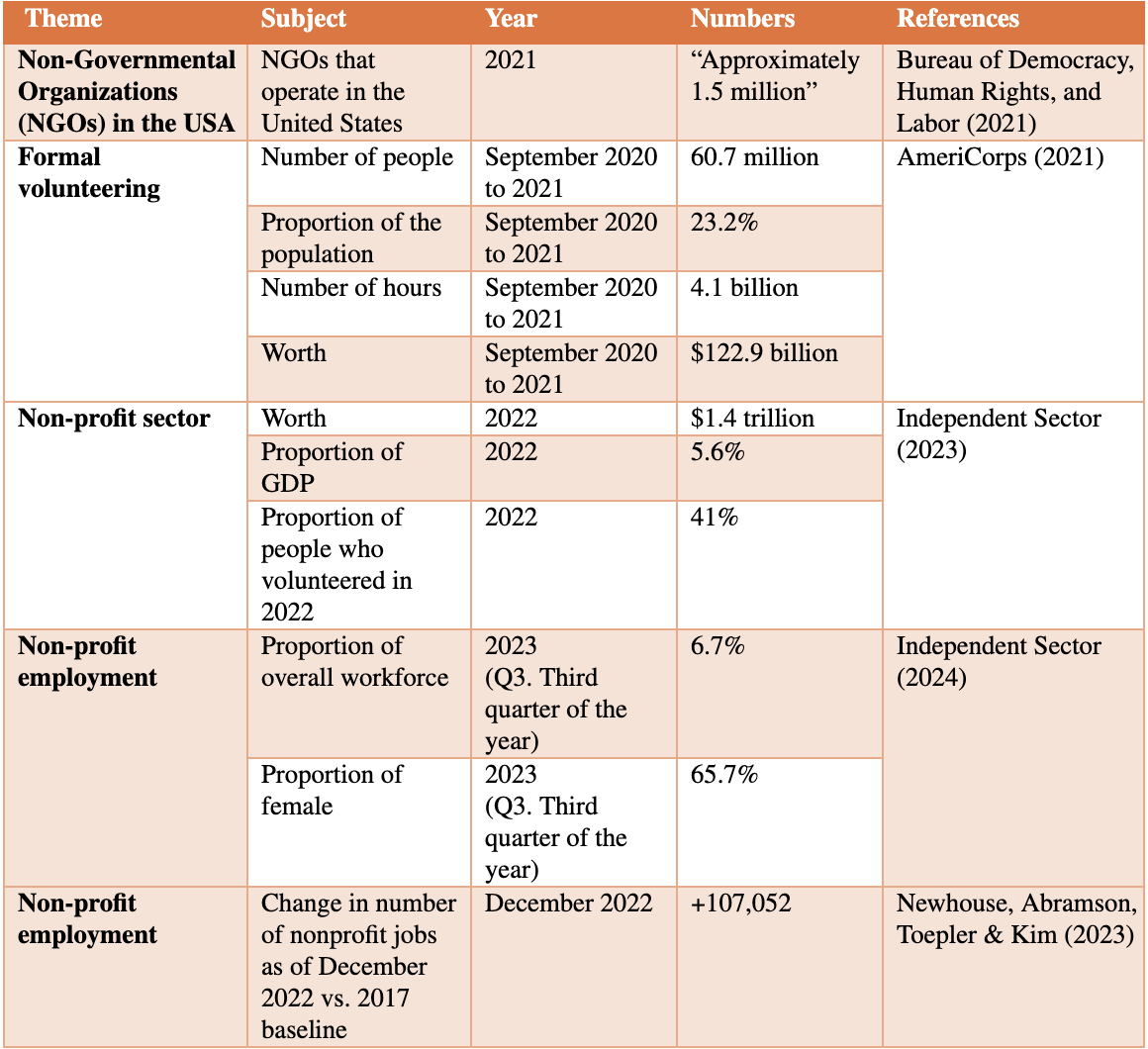

To juxtapose the high-level, nation-state, elitist form of Pygmalion democracy with the lived experience of individuals, groups, communities and societies within the larger configuration of social relations, we should also consider how people develop, organize, inter-mingle and build real-life experiences outside of geo-political machinations and considerations. Within the USA context, as per the illustration presented in Table I.2, in 2021 there were more than 1.5 million registered non-profit charitable organizations, including more than 60 million people volunteering more than 4 billion hours, and generating significant worth. In 2022, the non-profit sector is estimated to be worth $1.4 trillion in 2022.

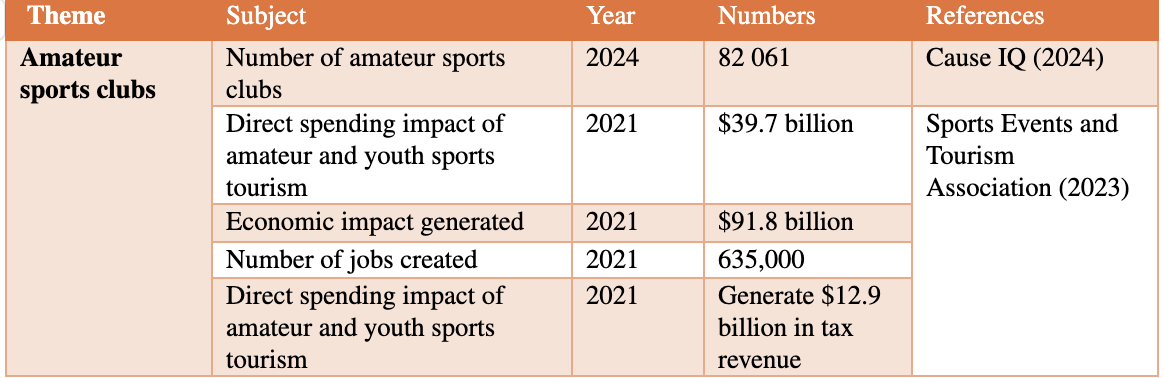

Similarly, the area of amateur sports in the USA presents a broad, vast network of sports, clubs, organizations, volunteers, economic impact and tourism (Table I.3).

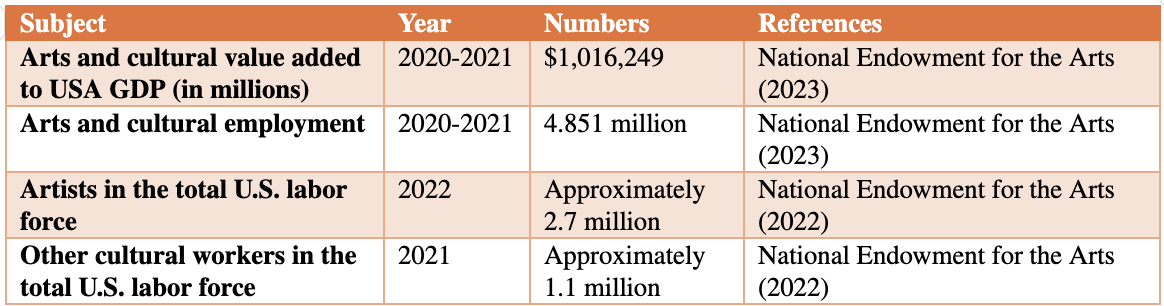

Lastly, the arts and cultural sectors in the USA are another significant force within civil society and communities, including more than 2.5 million artists and close to 5 million jobs (Table I.4).

Thus, we can denote that there is concurrently significant avarice, injustice and inequality, while many people are also engaged in a range of noble, uplifting and impactful activities aimed at building a better society. All of these individual efforts can, we believe, lead to diverse forms of collective mobilization. Acts of kindness and benevolence, even when not widely recognized, can be transformative, and may lead to broader conscientization. We are not saying this in a naïve wishful way but in a measured and hopeful sense that good deeds, actions, gestures and motivations are necessary and foundational to sustaining communities and societies. Yet, this part of the equation does not seem to be calculated within the broad strokes of normative, electoral Pygmalion democracy. How could there even be a discussion about democracy without the infinite acts and roles played by civil society organizations, often aimed at upholding communities. The fact that much of this service is undertaken without remuneration is almost astounding when juxtaposed against the hyper-neoliberal economic model and obsession that quantifies everything, often placing the military-industrial complex at the fore.

Every nation and society has these organizations, groups and actors that build and develop communities. The Pygmalion democratic model can derisively diminish all of these acts and actors, yet it is these people, communities and activities that underpin societies. The clash with geopolitics and nation-state representations can obscure the real-life concerns and challenges of working people and those building communities.

Conclusion

We started with the concept that we are living in a Pygmalion democracy, an almost fictive story about how everything is said to embellish the reality of the governance and organization and tangible power forces that exist to make us believe that we have ultimate freedom, notably through the vehicle of a two-party system and elections every few years. We also alluded to the film Field of Dreams, and the central (re-formulated) refrain If you build it, will they come. We are concerned that something has been built, and it is normatively considered to be beyond reproach. You have an opportunity to voice your proverbial opinion/vote through elections, which serve to legitimate the very structure that you may believe is causing you harm. It is even either ill-advised or unacceptable to question the whole operation (“if you don’t vote, you have no right to complain” is a common refrain). While large numbers of people do not participate in these normative elections, or do so knowing that they are not voting for their interests, or partake under duress, voting for the lesser-evil, or believe that that it is a scam meant to uphold a system that is very unlikely to change the material and real-life circumstances of working, marginalized, minoritized and other people.

Hurtado (2019) offers that “The Pygmalion effect is a type of self-fulfilling prophecy, a concept attributed to Robert Merton who said that ‘the self-fulfilling prophecy is, in the beginning, a false definition of the situation, evoking a new behaviour which makes the originally false conception come true. The specious validity of the self-fulfilling prophecy perpetuates a reign of error’”. What was potentially intended to positively change behaviour has, for many, led to discouragement, disengagement and disbelief.

When thinking of Pygmalion democracy, we should also ground the debate in the First Nations of the Americas. The notion that a higher form of democracy could be nourished on the back of cultural genocide that reduced the overall population by 90% is difficult to comprehend (Rasley, 2020). In the Americas, we are standing on unceded territories. The total population of the Americas before European contact is estimated between 90 and 112 million (Mann, 2005), with the majority being in what is now South America, and about 10% in what is now North America (Taylor, 2001). Treaties were broken (Pruitt, 2023), territories stolen (McGreal, 2012), policies and laws implemented to erase Indigenous cultures, spiritualities, languages and existence (MacNeill & Ramos-Cortez, 2024). Residential schools in Canada and many other countries, including in the USA, left a debilitating legacy of cultural and linguistic assimilation, abuse and sustained violence against Indigenous rights and sovereignty (CVRC, 2015; Gone et al., 2019). Extremely disproportionate incarceration rates, inferior schooling conditions, deficient health care standards, employment problems, racial discrimination and other issues characterize the context for many First Nations (CVRC, 2015; Government of Canada, 2023; United Nations, 2019).

According to Amnesty International (2024), “There are more than 5,000 different Indigenous Peoples around the world comprising 476 million people — around 6.2% of the global population. They are spread across more than 90 countries in every region and speak more than 4,000 languages.” In the Americas, it is customary to acknowledge that we are standing on unceded territory, but words are not enough. We need to rethink and reimagine our education, legal changes, engagement, solidarity and humanity, and the absence of truth, reconciliation and engagement with Indigenous Peoples underscores the thinness of the democratic project. An apology from the Vatican for the Discovery Doctrine that justified and laid the groundwork for European dispossession of First Nations territories for centuries was only given in 2022 (CBC News, 2022; also see Jeff Share’s chapter in this volume for a more complete description).

So we return to the essence, meaning, interpretation and mythology of democracy. Some 1500 years ago, there was a reference to city-states in Greece and the rule (kratos) of the people (dēmos) (Shapiro & Robert, 2024). Dictionaries and formal definitions provide a normative representation:

- government in which the supreme power is held by the people and used by them directly or indirectly through representation.

- a political unit (as a nation) that has a democratic government.

- belief in or practice of the idea that all people are socially equal. (Merriam-Webster, 2024)

Abraham Lincoln famously summarized democracy as “Of the people, by the people, for the people” (Cornell University, 2015). These normative perspectives and frameworks of democracy have long been held as the very meaning of the concept.

A number of philosophers, theorists and activists have sought to construct a more vibrant and meaningful form of democracy. There were many developments in the 1800s and 1900s that sought to develop progressive democracy, radical democracy, deliberative democracy and autonomist democracy, among other forms, including socialist and alternative conceptualizations (U.S Department of State, 2009).

We contend that Pygmalion democracy contradicts and is complicit with the thinner version of normative democracy that plays out in our societies. Over time, within the stew of sustained racism, sexism, xenophobia, discrimination, warfare and conflict, impoverishment, environmental degradation, inequalities and ineffectual elections, it is difficult and problematic to believe that we are in one of the dictionary definitions of democracy. The “power of the people” must also include an unpacking of power relations, how power works and how oppression can be orchestrated by and through inequitable power relations. The qualifier “sustained” in the previous sentence is fundamental to buttressing our contention that normative democracy is a mythology, a fantasy or a utopian image that does not apply to how society functions or how it can be transformed. This book seeks to extend this analysis to a number of contexts, countries, settings and frameworks, all aimed at problematizing Pygmalion democracy with the hope of developing a more vibrant, critically-engaged and socially-just democracy.

Although the central issue of media, communications and social media is addressed in a number of chapters in this book, we would like to simply note that unfiltered access to a variety of platforms, applications, sources, networks and people crossing linguistic, cultural, philosophical, political, geographic and other borders is an irrefutable reality. We can add to this artificial intelligence, algorithms, surveillance, manipulation and fake news and a host of potential bad actors as well as the need for critical media literacy. Taken together, there is ample room to construct and develop democracy and, concurrently, to distort and dismantle democracy. Broda (2024) presents the sentiment that there is growing polarization in media consumption, with many people locked into echo chambers that confirm strongly held biases and beliefs. Baron (2024) concurs with this view, and cautions about the impact of algorithms as well as the silos created within diverse perspectives. Newman (2024) fleshes out the problematic by underscoring the threat to investigative journalism through the proliferation of artificial intelligence. There is no doubt that political campaigns, embedded within the Pygmalion democracy era, are intertwined with and within social media (Zhang et al., 2024). We are now in a postdigital world (see Petar Jandrić’s chapter), one that straddles old and new media, human-made and artificially-constructed messages and content, as well as other forms of life, and diverse and divergent forms of agency. Carr (2020, 2022) has pointed out that we are also shifting between Democracy 1.0 (traditional/normative), Democracy 2.0 (interactive with the potential for social justice and mini-publics) and Democracy 3.0 (surveillance, algorithmic and artificial intelligence), all within the context of neoliberalism and enhanced communications.

Michael J. Sandel’s Democracy’s Discontents (2022) makes the case that “people feel that they don’t have a say in how they are governed, that their voice doesn’t matter,” “people feel, for some time, that the moral fabric of community, to the nation, people hunger for a sense of belonging, a sense of pride, a sense of solidarity, and people feel unmoored. … These are two deep sources of the discontent that this (2024) election was about…”.[2] Several chapters in this book take up this theme that we are not living in the democracy that we think we are, that many people feel a sense of helplessness and hopelessness, which makes turning to extreme right-wing and even fascist options a reasonable, “common sense” choice. This is where we believe there is a great danger in perpetuating the “system” as is.

What does it all mean, and what can/should we do? We hope that this book might provide some knowledge, some sign-posts, some proposals and some motivation to confront Pygmalion democracy. Importantly, we hope that this project might be part of the numerous, broad, insightful and creative efforts to build a more meaningful democracy for the people.

To conclude this introduction, after which we include the abstracts of all of the chapters, we offer a few suggestions below, none of which are easily realized but which, together, can hopefully ignite and initiate some meaningful reflection. Since no one person, group, community, society, nation has the answer…:

- We must re-imagine democracy because too much emphasis on normative electives has diminished the real essence of building a society and a democracy; democracy should not be about a horse-race to win by a slight margin, after years of fundraising, campaigning and “politicking”; significant efforts should be made to re-construct processes and systems that aim to be and to build democracy;

- Teach about/for peace, and teach for social justice, anti-racism, inclusion, equity and social change… and democracy; education at the formal, informal and nonformal levels is fundamental to social change (Carr & Thésée, 2019);

- End the arms race and arms development, production, sales and usage; there is no noble purpose to aiding and abetting in the killing industry; this will require democratic engagement through laws, through education, through civil society and through social movements;

- Cultivate and recognize civil society engagement; individuals, communities, movements, organizations, etc. are not simply nation-states; allow people to design democratic processes so that their voice, well beyond Pygmalion elections, really counts;

- End tax-havens for the ultra-wealthy; how can NOT paying taxes where you live benefit the common good?; this seems to be a blatantly obvious proposal but true democratic action is required to rectify the situation;

- Problematize formal and informal support for brutality and repression; we are complicit in what the nation-state does in our names so we need to have a say in the nefarious part of militarization and conflict; render transparent the military-industrial complex, the nefarious web of spy-agencies and contacts/contracts to underwrite conflict and warfare;

- Engage with, respect and support Indigenous peoples (languages, cultures, rights, territory, sovereignty); building a democracy on the denigration of the First Nations is not a vibrant, decent, inspiring and morally-just project; work toward sovereignty and reconciliation;

- Stop feigning that the environment is not a central issue to all humans and species and our very existence; this is a global matter, and must be addressed through national and international protocols, agreements and projects;

- Emphasize humility; the wonderful work of Paulo Freire and many others in the critical pedagogy movement can be uplifting, and should be integrated through school curricula, pedagogy and epistemological projects;

- Cultivate meaningful, pertinent and critically-engaged dialogue in all sectors of society; it is not, or should not be, about sound-bites, low blows, gotcha-moments and Pygmalion declarations about being the best; this may mean curtailing the endless electoral campaigns, and honing in on true democratic engagement before, during and after elections;

- Create more space and support for culture and the arts throughout society; consider participatory budgeting for the arts at an equal level of funding as defence;

- We are not born racist and sexist; if we become racist and sexist, or not, what does education have to do with it? And what does democracy have to do with it?; let’s problematize education and democracy throughout societal deliberations rather than believing that we are achieving democracy in and through education; more open and deliberative democracy should be created to advise and make decisions beyond partisan political interests;

- Make nonviolence a central pillar to conflict resolution; killing others is not the solution, nor is domestic violence, bullying, intimidation, etc.; seek and implement preventative and holistic measures that consider socio-economic issues;

- Promote intercultural relations based on social justice, and address racism, sexism and xenophobia (through laws, education, policies, economics and socio-cultural relations);

- Support media literacy and deliberative democracy in authentic, meaningful sustained ways;

- Give someone you do not know a hug, and smile at strangers, be kind, engage in solidarity, be peaceful, and think about solidarity beyond borders and identities.

There is no one best person, no one best country. We are all in the same boat, and, despite the rising sea-levels and turbulence, the boat can float, if we want it to.

References

AmeriCorps. (2021). Volunteering and Civic Life in America. https://americorps.gov/sites/default/files/document/volunteering-civic-life-america-research-summary.pdf

Amnesty International. (2024). Indigenous Peoples’ Rights. https://www.amnesty.org/en/what-we-do/indigenous-peoples/#:~:text=There%20are%20more%20than%205%2C000,speak%20more%20than%204%2C000%20languages

Amy, Douglas J. (2020). The Two-Party Duopoly. Second-rate democracy. https://secondratedemocracy.com/the-two-party-duopoly/

Baron, I. Z. (2024). Exploring the Threat of Fake News: Facts, Opinions, and Judgement. Journal of Political Communication. 77(2). https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/10659129241234839

Banerjee, S. B. (2022). Decolonizing Deliberative Democracy: Perspectives from Below. J Bus Ethics, 181, 283–299. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-021-04971-5

Broda, E. (2024). Media fragmentation and political polarization: A study of mainstream and alternative media consumption. Journal of Political Communication, 23(1), 45-62. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/23808985.2024.2323736

Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor. (2021). Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) in the United States. https://www.state.gov/non-governmental-organizations-ngos-in-the-united-states/

CBC News. (2022, July 25). Pope Françis apologizes for forced assimilation of Indigenous children at residential schools. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/edmonton/edmonton-pope-alberta-apology-1.6530947

Carr, Paul R. (2020). Shooting yourself first in the foot, then in the head: Normative democracy is suffocating, and then the Coronavirus came to light. Postdigital Science and Education, 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-020-00142-3

Carr, Paul R. (2022). Insurrectional and Pandoran Democracy, Military Perversion and The Quest for Environmental Peace: The Last Frontiers of Ecopedagogy Before Us. In Jandrić, P. & Ford, D. R. (Editors), Postdigital Ecopedagogies (pp. 77-92). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-97262-2_5

Carr, P. R., & Thésée, G. (2019). “It’s not education that scares me, it’s the educators…”: Is there still hope for democracy in education, and education for democracy? Myers Education Press.

Carr, Thésée & Rivas-Sanchez (Eds). (2023). The Epicenter: Democracy, Eco*Global Citizenship and Transformative Education / L’épicentre : Démocratie, Éco*Citoyenneté mondiale et Éducation transformatoire / El Epicentro: Democracia, Eco*Ciudadanía Mundial y Educación Transformadora. DIO Press.

Cause IQ. (2024). Directory of amateur sports clubs. https://causeiq.com/directory/amateur-sports-clubs-list/

Ceaser, J. W. (2012). The origins and character of American Exceptionalism. American Political Thought, 1(1), 3–28. https://doi.org/10.1086/664595

Chomsky, Noam. (2004). Hegemony or survival: America’s quest for global dominance. Penguin.

Chomsky, Noam. (2022). Chomsky on Democracy and Education. Routledge.

Commission de vérité et réconciliation du Canada (CVRC). (2015). Honorer la vérité, réconcilier pour l’avenir : sommaire du rapport final de la Commission de vérité et réconciliation du Canada. Commission de vérité et réconciliation du Canada. https://lc.cx/CzFo6q

Cornell University. (2015). Transcript of Cornell University’s Copy. https://rmc.library.cornell.edu/gettysburg/good_cause/transcript.htm

de Tocqueville, A. (2002). Democracy in America. University Of Chicago Press. (Original work published 1835)

Femia, Joseph V. (2003). Marxism and Democracy. Oxford University Press. https://academic.oup.com/book/10904

Giroux, Henry. (2018). American Nightmare: Facing the Challenge of Fascism. City Lights Publishers.

Giroux, Henry & DiMaggio, Anthony R. (2024). Fascism on Trial: Education and the Possibility of Democracy. Bloomsbury Academic.

Government of Canada. (2023). An update on the socio-economic gaps between Indigenous Peoples and the non-Indigenous population in Canada: Highlights from the 2021 Census. https://www.sac-isc.gc.ca/eng/1690909773300/1690909797208#exsum

Gone, J. P., Hartmann, W. E., Pomerville, A., Wendt, D. C., Klem, S. H., & Burrage, R. L. (2019). The impact of historical trauma on health outcomes for Indigenous populations in the USA and Canada: A systematic review. American Psychologist, 74(1), 20-35. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/amp0000338

Guardian investigation team. (2021, October 3). Pandora papers: biggest ever leak of offshore data exposes financial secret of rich and powerful. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/news/2021/oct/03/pandora-papers-biggest-ever-leak-of-offshore-data-exposes-financial-secrets-of-rich-and-powerful

Henry, J. (2016). Taxing Tax Havens: How to Respond to the Panama Papers. Foreign Affairs. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/belize/2016-04-12/taxing-tax-havens

Henry, F. & Tator, C. (2009). Colour of Democracy Racism in Canadian Society. Nelson Education.

Hurtado, C. (2019, August 14). The Pygmalion effect. Medium. https://medium.com/@cayehurtado/the-pygmalion-effect-28a65d2346eb

Independent Sector. (2023). Health of the U.S. Nonprofit Sector. https://independentsector.org/resource/health-of-the-u-s-nonprofit-sector/#:~:text=Nonprofits%20comprised%205.6%25%20of%20GDP,to%20the%20economy%20in%202022

Independent Sector. (2024). Health of the U.S. Nonprofit. Sector: A Quarterly Review: January 2024. https://independentsector.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Health-of-the-US-Nonprofit-Sector_Quarterly-Review_Jan-2024.pdf

International Consortium of Investigative Journalists – ICIJ. (2017, January 31). Explore the Panama Papers Key Figures. https://www.icij.org/investigations/panama-papers/explore-panama-papers-key-figures/

Internal Revenue Service. (2019). Nonprofit Charitable and Other Tax-Exempt Organizations, Tax Year 2019. https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/p5331.pdf

López, Ian Haney (2021, July 9). Can Democracy Survive Racism as a Strategy? Protect Democracy https://protectdemocracy.org/work/can-democracy-survive-racism-strategy/

MacNeill, T., & Ramos-Cortez, C. (2024). Decolonial economics: Insights from an Indigenous-led labour market study. Economy and Society, 53(3), 449-477. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085147.2024.2382628

Mann, C. C. (2005). 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus. Knopf.

McGoey, S. (2021, April 6). Panama Papers revenue recovery reaches $1.36 billion as investigations continue. International Consortium of Investigative Journalists – ICIJ. https://www.icij.org/investigations/panama-papers/panama-papers-revenue-recovery-reaches-1-36-billion-as-investigations-continue/

McGreal, C. (2012, May 4). US should return stolen land to Indian tribes, says United Nations. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2012/may/04/us-stolen-land-indian-tribes-un

National Endowment for the Arts. (2023). Key to Arts and Cultural Industries U.S., 2021 [dataset]. https://www.arts.gov/impact/research/arts-data-profile-series/adp-34

National Endowment for the Arts. (2022). Artists and Other Cultural Workers. https://www.arts.gov/impact/research/NASERC/artists-and-other-cultural-workers

Newhouse, C. L., Abramson, A. J., Toepler, S. & Kim, M. (2023). Nonprofit Employment Estimated to Have Recovered from COVID Pandemic-Related Losses as of December 2022. https://nonprofitcenter.schar.gmu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/George-Mason-University-%E2%80%93-Nonprofit-Employment-Data-Project-%E2%80%93-Briefing-1.pdf

Newman, N. (2024). Journalism, media, and technology trends and predictions 2024. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/journalism-media-and-technology-trends-and-predictions-2024

O’Donovan, J., Wagner, H. F., & Zeume, S. (2019). The value of offshore secrets: Evidence from the Panama Papers. The Review of Financial Studies, 32(11), 4117-4155. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhz017

Pruitt, S. (2023, July 12). Broken Treaties With Native American Tribes: Timeline. History. https://www.history.com/news/native-american-broken-treaties

Rasley, J. (2020). Reparations for Native American Tribes? Wicazo Sa Review, 35(1), 100-108. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48747388

Sandel, Michael J. (2022). Democracy’s Discontents. Belknap Press.

Shapiro, I., & Robert, A. D. (2024, November 11). Democracy. Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/democracy

Smith, E., Shiro, A., Pulliam, C., & Reeves, R. (2022, June 29). Stuck on the ladder: Wealth mobility is low and decreases with age. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/stuck-on-the-ladder-wealth-mobility-is-low-and-decreases-with-age/

Sports Events and Tourism Association. (2023). 2021 State of the Industry Report. https://research.sportseta.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/2021-State-of-the-Industry-Report.pdf

Steinberg, S. & Down, B. (Eds.) (2020). The SAGE Handbook of Critical Pedagogies (three-volume set). Sage.

Stopler, Gila. (2021). The personal is political: The feminist critique of liberalism and the challenge of right-wing populism, International Journal of Constitutional Law, 19 (2), 393–402. https://doi.org/10.1093/icon/moab032

Taylor, A. (2001). American Colonies. Viking.

United Nations. (2019). State of the World’s Indigenous Peoples: 4th Volume. https://social.un.org/unpfii/sowip-vol4-web.pdf

United States Government. (2022). Best Practices for Identifying and Protecting Tribal Treaty Rights, Reserved Rights, and Other Similar Rights in Federal Regulatory Actions and Federal Decision-Making. https://www.denix.osd.mil/na/denix-files/sites/42/2023/02/Interagency-TTR-Best-Practices-Report.pdf

U.S. Department of State. (2009, January 20). The Progressive Movement and U.S. Foreign Policy, 1890-1920s. https://2001-2009.state.gov/r/pa/ho/time/ip/108646.htm

Merriam-Webster. (2024). Democracy. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/democracy#:~:text=A%20democratic%20system%20of%20government%20is%20a%20form%20of%20government,usually%20involving%20periodic%20free%20elections.

Zembylas, M. (2022). Decolonizing and re-theorizing radical democratic education: Toward a politics and practice of refusal. Power and Education, 14(2), 157-171. https://doi.org/10.1177/17577438211062349

Zhang, Y., Lukito, J., Suk, J., & McGrady, R. (2024). Trump, Twitter, and Truth Social: How Trump used both mainstream and alt-tech social media to drive news media attention. Journal of Information Technology & Politics. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/382751418_Trump_Twitter_and_Truth_Social_how_Trump_used_both_mainstream_and_alt-tech_social_media_to_drive_news_media_attention

- Noam Chomsky has written so extensively on a range of topics, including linguistics, the media, American hegemony and foreign policy, that a single reference is not sufficient. The Chomsky archive contains dozens of books, articles, interviews, videos and other publications of interest: https://chomsky.info/. His contribution to building a robust and critical democracy over the past several decades is inestimable. ↵

- This quote is from an November 16, 2024, interview with Michael Sandel on Amanpour and Company, available on YouTube, on the subject of “What Trump’s Won Says About American Society”. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Um017R5Kr3A ↵