1. If it sounds too good to be true… The mythology of (normative) elections building transformative forms of democracy

Paul R. Carr

Abstract

The parallel between horse-racing, reality shows and electoral campaigns, especially in the 2024 USA presidential campaign, I believe, is not inconsequential, nor impertinent. All three aim to win the race or the competition with whatever it takes. Yet, it is not clear what any of them has to do with building a democracy. I guess we then circle back, as is the theme of this book, to the discussion around, importantly, what is a democracy. If it principally involves holding elections, despite however legitimate, meaningful, inclusive, engaging and democratic they may or could be, then we can probably infer that a thin, weak and somewhat alienating form of democracy is in play. There are a ton of caveats here, and these affirmations are not meant to degrade, disparage or discount a lot of well-intentioned people, groups, communities and causes that become enmeshed within the voting project. I wish to elaborate on and discuss in this chapter, within the Pygmalion framework, two central pillars to understanding normative democracy today: the USA, as a nation-state, and elections, within the normative framework. To frame the former, I will draw on diverse rankings, classifications, frameworks, models and indicators that aim to present how democratic countries or nation-states are, or are considered to be, democratic. For the latter, I will present some thoughts on, and critiques of, normative elections, extending an analysis that I have been developing over the past few years. I will conclude with some thoughts on the state of democracy, and where we might be headed.

Keywords: Pygmalion democracy, elections, American exceptionalism, corruption, freedom, hegemony, human rights, social justice.

Introduction

I have started writing this chapter eight days before the USA presidential election of 2024. On the one hand, should this be a dramatic, transformative moment in human history or just another election, unlike all the others that take place within OECD countries every couple of years? Or is this the election of all elections? Of course, every USA election is characterized as the most important, the one that will define a generation, the definitive shaping of the country and world for the next several years. Yet, this one seems exceptionally charged with everything possible of an off-the-rails, whodunit spectacle. That may be too raw of a depiction, but this is an election that has included, quite literally, a four-year campaign, and countdowns every hundred, fifty, twenty and ten days that reinforce the notion that this is one helluva horse race. Who has the best jockey, the quickest horse, what are the conditions on the track, how do the trainers affect the process, what about the diet of the thoroughbreds, what is the betting-line, how does it change as we get closer to the starting-line? Is this a text about a horse race or an electoral campaign? It is about both, but the real question should be: what is the connection to democracy?

Like many people around the world, I have been watching, listening to, hearing and reading about this election over the past four years. There has been the endless polling, the negative and even toxic advertisements, the avalanche of funding and fundraising, which is supposed to be a barometer of how successful and popular a candidate is, the suffocating and draining “late-breaking news” cable channels that cover pretty well every detail and pronouncement of the candidates, especially the two names at the top of the ticket, and all the other trappings that are meant to (supposedly) encapsulate democracy. This does seem like a surreal, collectively experienced, reality-show experience. We are living through it, akin to watching how participants maneuver in a loft or on an island or a dance floor or in a kitchen or, at the pinnacle, in a boardroom. It is as though people are being voted out of these games, after which they can potentially become an influencer or some other public figure, and the objective is to stay in the public spotlight. Who will be out or off, or who will be fired, has become the climax point for much of this vaudeville show. There has been a litany of insults, accusations, racist and sexist affirmations, misinformation, misrepresentation and the always popular “fake news” throughout the past four years.

The 2024 USA campaign has been a real barnburner, and despite a Pygmalion discourse about everyone being neighborly, looking out for one another and being concerned about “democracy,” we can also see a massive alignment of people who support the person, the party and the movement that are supposedly “undemocratic”. If the supposed anti-democratic candidate wins, after all the bells and whistles and debates and rallies and non-stop reporting and endless social media, does that mean that people want an “anti-democratic” democracy? What does it say about the culture, the people, the system? Are the people utterly delusional, totally duped and hell-bent on becoming fascist or is the electoral system so contaminated and nefarious that it no longer attempts to instill, cultivate and reinforce democracy? Or does the will of the people simply equate to democracy? It can be entertaining, and the ratings are where it’s at.

Let us not overlook the financial scaffolding strung together to generate profits through spin-offs, advertisement revenue, product placement, syndication, free stuff that the most successful and wealthy companies may wish to shower on the most visible entities and all the other nooks and crannies that flow in and out of these corporate behemoths. Why are there super-packs and billionaires lurking in every corner? Everyone has endless platforms, media outlets clamoring at the door, social media and distribution lists and private networks, so why the need for endless fundraising? Focusing on raising funds means less focus on people and engagement, or might political forces argue that there is no engagement without the funds? Why does the mainstream and cable media report on the funds raised and spent as if this is an accurate barometer of the health of the nation?

The parallel between horse-racing, reality-shows and electoral campaigns, especially in the 2024 USA presidential campaign, I believe, is not inconsequential, nor impertinent (Carr, 2022). All three aim to win the race or the competition with whatever it takes. Yet, it is not clear what any of them has to do with building a democracy. I guess we then circle back, as is the theme of this book, to the discussion around, importantly, what is a democracy. If it principally involves holding elections, despite however legitimate, meaningful, inclusive, engaging and democratic they may or could be, then we can probably infer that a thin, weak and somewhat alienating form of democracy is in play. There are a ton of caveats here, and these affirmations are not meant to degrade, disparage or discount a lot of well-intentioned people, groups, communities and causes that become enmeshed within the voting project. Despite all the shortcomings and misgivings, I do vote but I do not believe that the large blocks of people who choose not to do so are any less important.

I wish to elaborate on and discuss in this chapter, within the Pygmalion framework, two central pillars to understanding normative democracy today: the USA, as a nation-state, and elections, within the normative framework. To frame the former, I will draw on diverse rankings, classifications, frameworks, models and indicators that aim to present how democratic countries or nation-states are, or are considered to be, democratic. For the latter, I will present some thoughts on, and critiques of, normative elections, extending an analysis that I have been developing over the past few years (Carr, forthcoming). I will conclude with some thoughts on the state of democracy, and where we might be headed.

Some ways of thinking about the USA and democracy

As I noted in the introduction to this chapter, it is almost impossible to look the other way and to not be somewhat or even massively aware of the USA electoral process. Unlike other countries, the USA is still within the Empire phase or stature, albeit on a steep decline, and the world is watching and reporting on and seeking to understand what it means for them, for us and for everyone. The same lens and focus are not accorded by the Empire to other countries, and it is likely reasonable to believe that coverage of the outside world by the USA is disproportionately limited compared to how the outside world considers its relations, interests, positioning and existence in relation to the USA. I will admit to a guilty pleasure, and I’m not sure if it is a pleasure or how it leads to guilt or culpability: I often listen to FOX on the radio when I’m driving about, and I probably consume more social media, podcasts, YouTube clips and the like that flow from the presumably right-wing in the USA. Why do I do it? This is not a criminal offense, and despite my partner and a good friend with whom I converse every day about the political landscape of the USA, yet I am entirely consumed with attempting to decipher where this worldview of greatness, natural superiority, strident patriotism, unrestrained militarism and a hyper-sensibility to “others” comes from. On the one hand, the USA is simply people, like everywhere, the vast majority sharing broad and decent and noble characteristics, traits and values with people around the world: the desire to have a family, build communities, have compassion for others, not glorify killing and war, enjoying cultural life together. So where do the finely tuned hegemony and bluster and hyper-geopolitical maneuvering come from? Is it because the USA is the most democratic country and, thus, justly deserves to dominate the world?

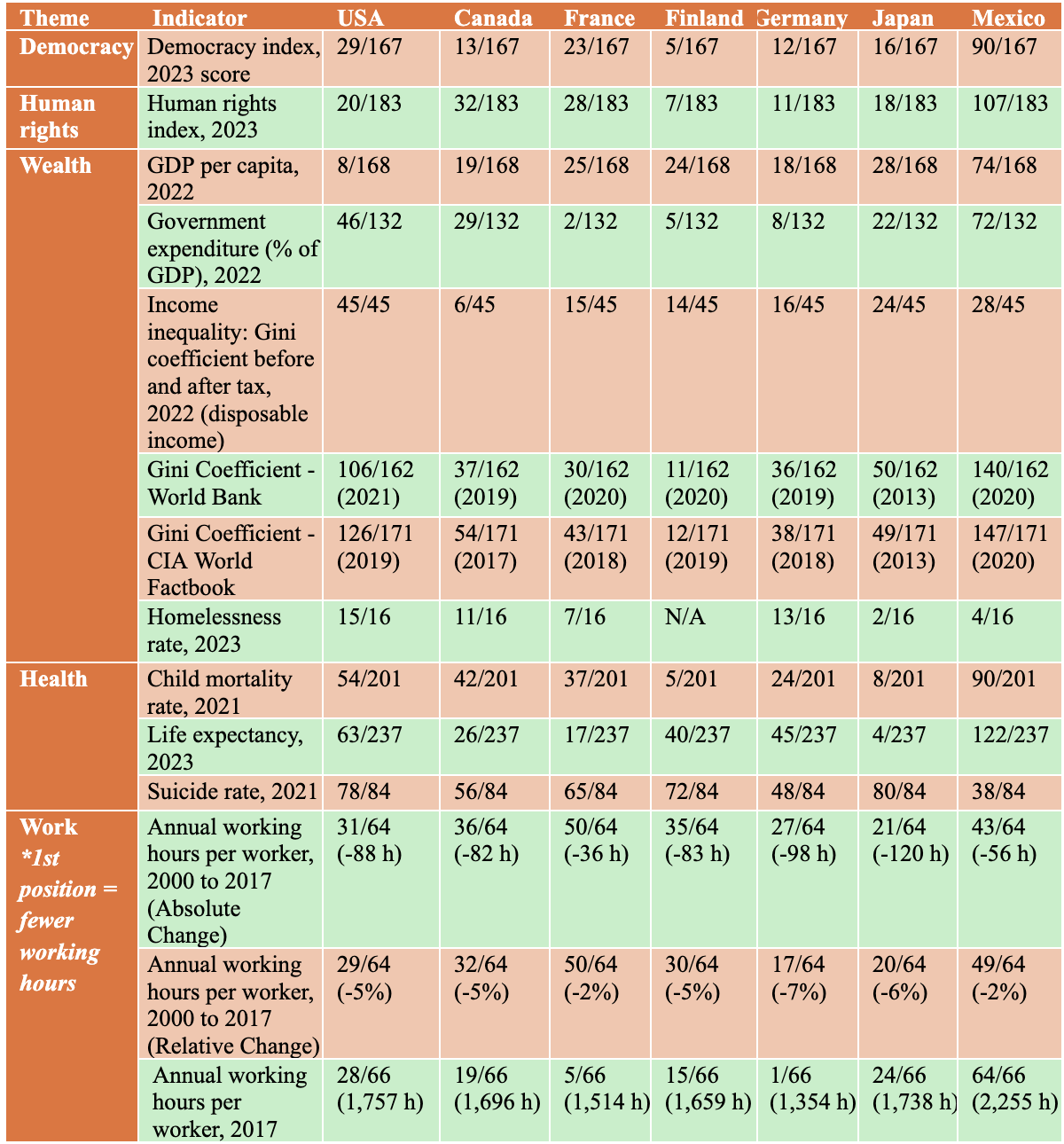

I will now present some rankings and data of nation-states related to democracy. As a preamble to the data that I present below, I would highlight that no one indicator, measure, evaluation or judgment is conclusive, nor comprehensive. Most of the overseeing bodies, sources and groups that undertake to present these datasets are lodged in and funded by the Global North, have conscious or unconscious biases related to the traditional capitalist (free market), liberal democratic model, and clearly have more and better access to information in the OECD countries than in other nations. Having presented those caveats, that we can’t fully conclude completely and without reservation which country is the most or the least democratic, we can start to develop a meaningful portrait and understanding of how nation-states develop, and also how they face significant challenges. To be more direct: it is difficult to extol the virtues of democracy within a country when we also clearly see racism, murder, femicide, diminished rights, corruption, weak press freedoms, warfare, diminished environmental conditions, etc. My interest here is to simply illustrate how no country has achieved the ultimate level of epiphanic democracy. Most of the tables below have been constructed using diverse datasets, and, to facilitate some basic comparisons, I have targeted seven countries (the USA, Canada, France, Finland, Germany, Japan and Mexico), knowing that this is for illustrative purposes only, and that I have not presented all the available data for all nation-states. Undoubtedly, comparisons will always lead to myriad problems and difficulties with interpretation but, nonetheless, they can help us develop a sense of the scope and depth of democracy within each complexified society. Again, within the Pygmalion framework, a starting point is that the USA is portrayed or has portrayed itself to be the leading and “greatest” country, the “voice of the free world,” and the most democratic nation. Thus, with all these provisos and mises en garde, I wish to contextualize and elucidate the real potential for democracy within nation-states.

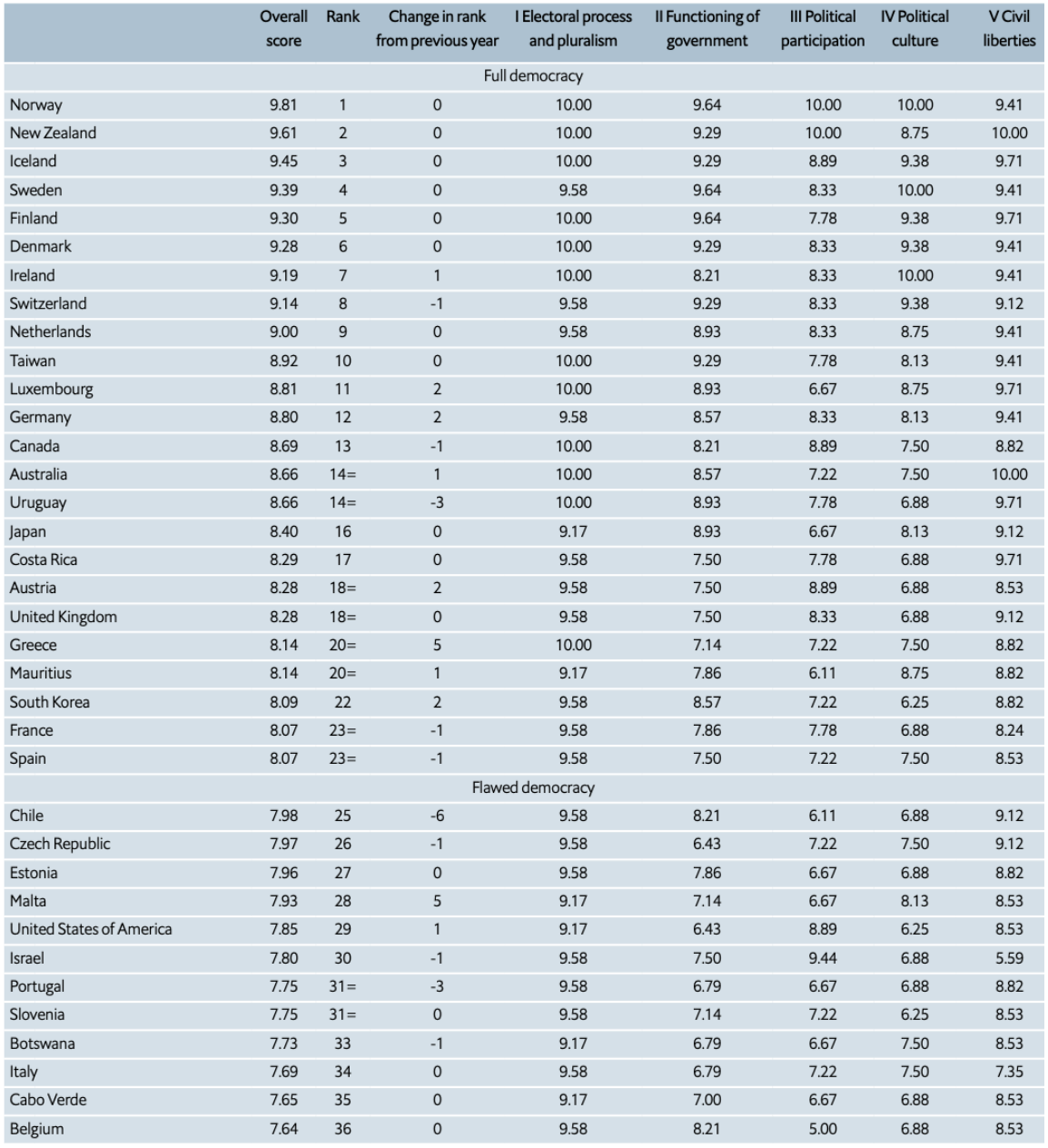

To start with, The Economist magazine and its research unit (The Economist Intelligence Unit, 2024) produce an annual Democracy Index that provides a ranking and overall score for countries. The following criteria are used to ground their evaluation: electoral process and pluralism; functioning of government; political participation; political culture; and civil liberties.

The USA is classified 29th out of roughly 200 countries, and is in the “flawed democracy” category, just below the “full democracy” level.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) provides a range of studies, analyses and reports, and describes itself as follows:

is an international organisation that works to build better policies for better lives. We draw on more than 60 years of experience and insights to shape policies that foster prosperity and opportunity, underpinned by equality and well-being.We work closely with policy makers, stakeholders and citizens to establish evidence-based international standards and to find solutions to social, economic and environmental challenges. From improving economic performance and strengthening policies to fight climate change, to bolstering education, and fighting international tax evasion, the OECD is a unique forum and knowledge hub for data, analysis and best practices in public policy. Our core aim is to set international standards and support their implementation, and help countries forge a path towards stronger, fairer and cleaner societies.

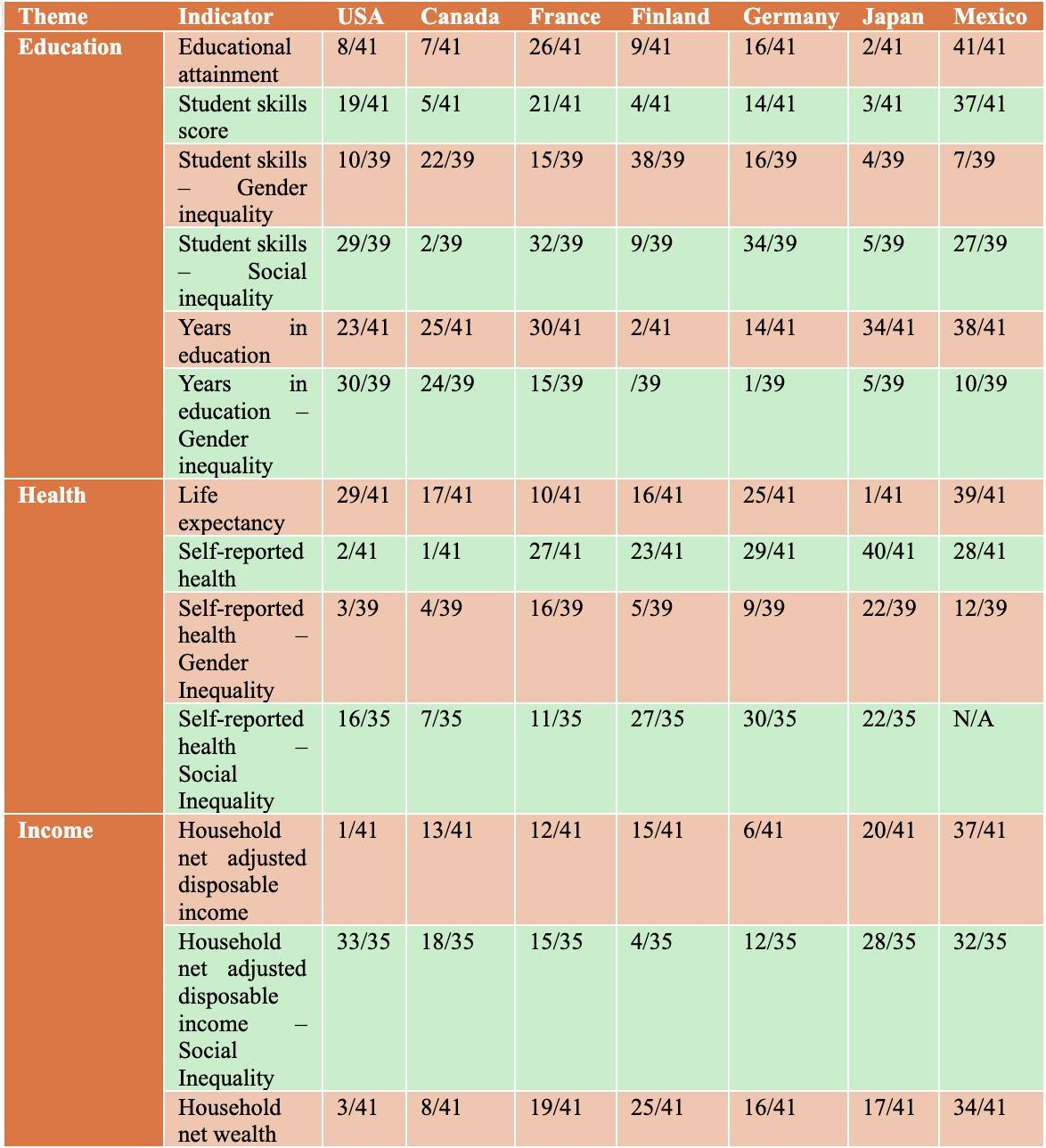

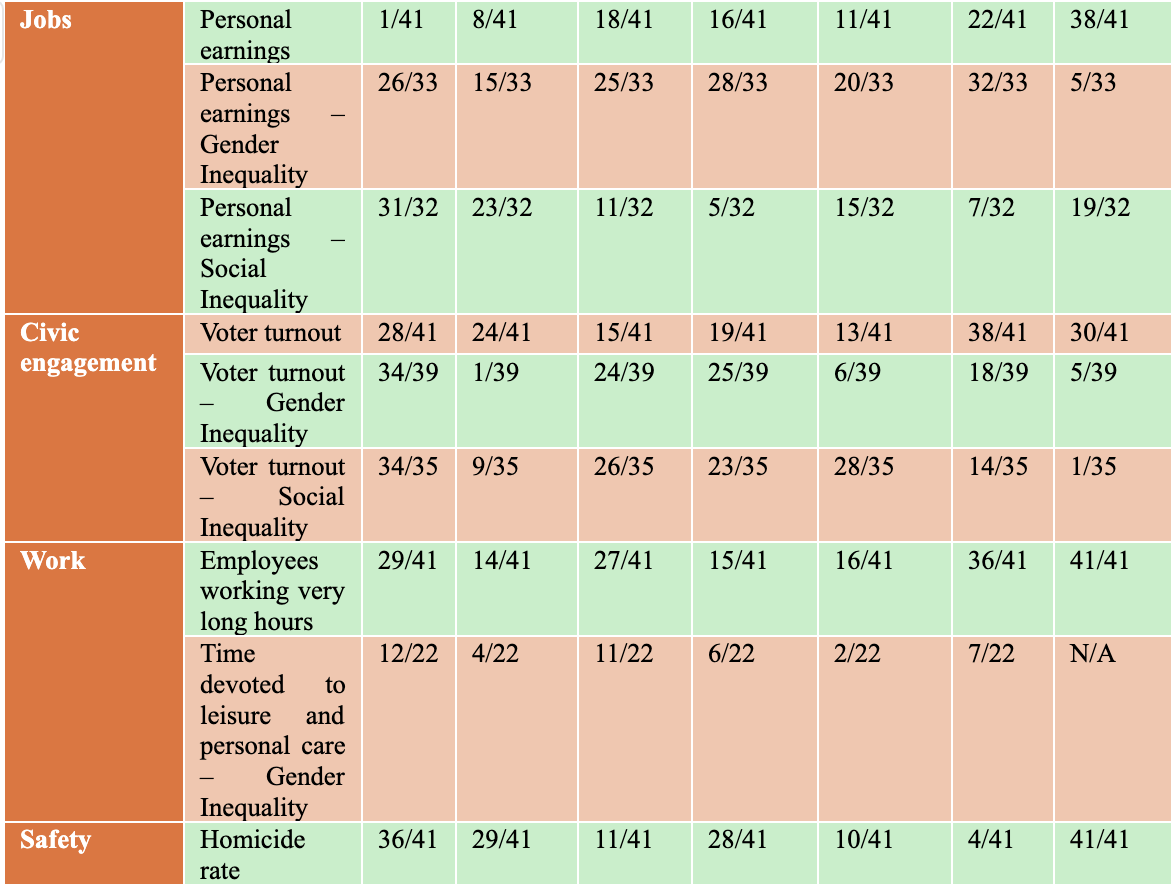

Based on studies undertaken in 2023, we can develop a profile of the selected countries at a comparative level. The second number in the table refers to the number of countries in the sample. I have compiled the data around themes, highlighting the indicator at a more micro level. The themes here are: education; health; income; jobs; civic engagement; work; and safety.

In sum, the indicators where the USA stands out positively (generally in the top ten countries) are mainly those related to income and wealth. This is the case for Household net adjusted disposable income (1st/41), Household net wealth (3rd/41), Personal earnings (1st/41) and GDP per capita (8th/168). However, the USA ranks particularly poorly on inequity indicators. Indeed, most selected inequity indicators illustrate a larger gap in the USA in terms of education, income, jobs, work or wealth than in the other selected countries: Student skills – Social inequality (29th/39); Years in education – Gender inequality (30th/39); Household net adjusted disposable income – Social Inequality (33th/35); Personal earnings – Gender Inequality (26th/33); Personal earnings – Social Inequality (31th/32); Time devoted to leisure and personal care – Gender Inequality (12th/22); Gini coefficient before and after tax (disposable income) (45th/45); Gini Coefficient – World Bank (106th/162); Gini Coefficient – CIA World Factbook (126th/171); and Homelessness rate (15th/16). The Gini Coefficient is perhaps the most important and significant measure of a society’s development as it specifically relates to wealth distribution and social justice within a society. The USA appears to be the most or, at the very least, one of the most inequitable societies in the (so-called) industrial, developed, Western world, in which comparative nations are included in the ranking. Similarly, there are many complexities to documenting and understanding homelessness but the USA ranking here is also a concern.

It is curious to note an inversely proportional relationship between the index of Life expectancy and that of Self-reported health or even Self-reported health – gender inequality. For the USA, we, thus, note a very high ranking for Self-reported health (2nd/41) and Self-reported health – gender inequality (3rd/39) but a very low comparative ranking for Life expectancy (29th/41). Americans believe, according to these data, that they have comparatively higher health outcomes than they actually do have in reality. In the opposite case, Japan ranks first in terms of Life expectancy, but the population’s opinion places the country near the bottom of the scale (40th/41) for Self-reported health.

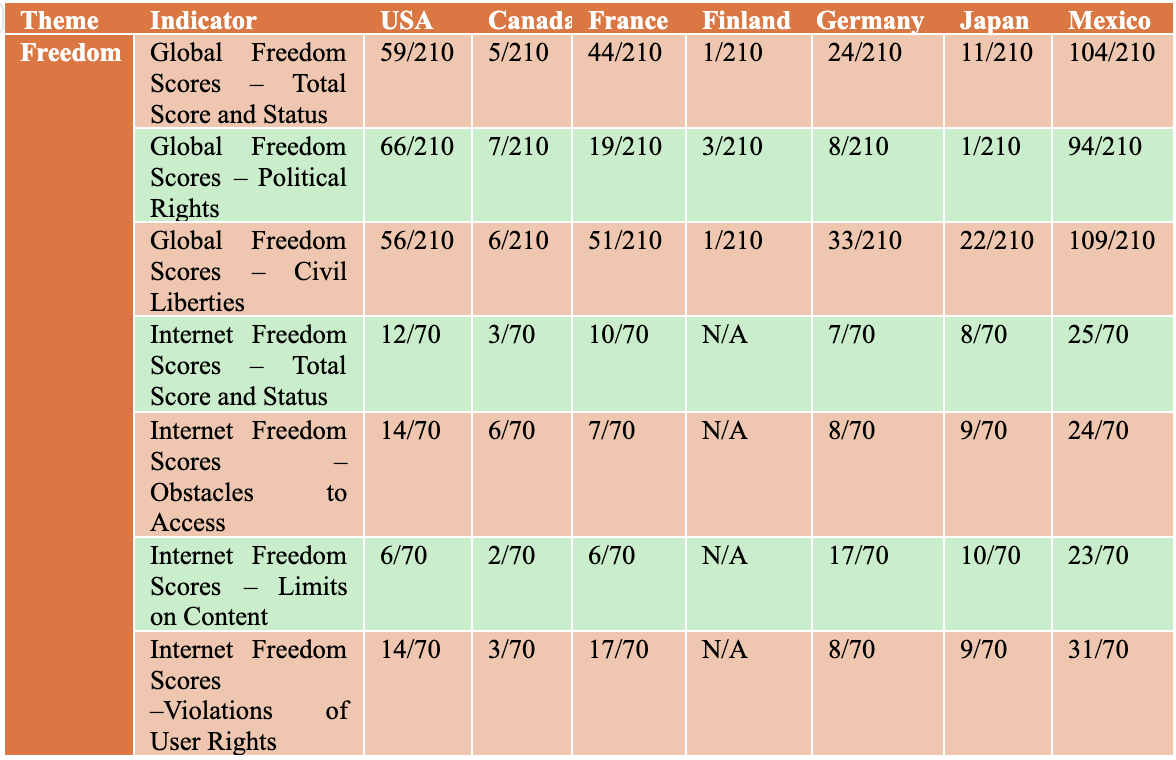

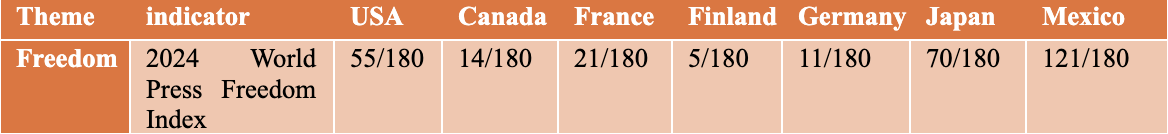

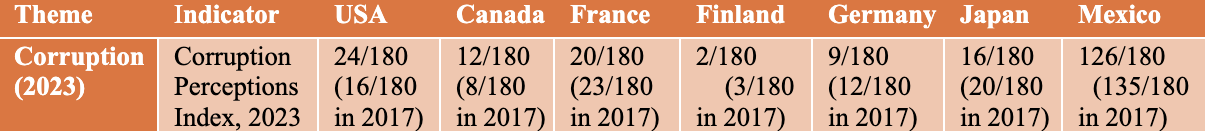

When we consider rankings produced by Freedom House (2024) and Reporters Without Borders (2024), we are presented with a broad and diverse range of comparative indicators. Table 1.3, with Freedom House (2024) rankings, includes scores for global freedom, political rights, civil liberties and internet freedom. The USA generally scores poorly concerning freedom, except in relation to internet access and content. Reporters Without Borders (2024) (see Table 1.4) underscores that the USA is almost always ranked behind Canada, France, Finland, Germany and Japan regarding the World press freedom Index.

Transparency International places the USA 24th out of 180 countries, near the bottom of OECD nations, in terms of corruption on its Corruption Perceptions Index.

The Our World in Data organization is based at the University of Oxford, with the following mission:

We take a broad perspective, covering an extensive range of aspects that matter for our lives. Measuring economic growth is not enough. The research publications on Our World in Data are dedicated to a large range of global problems in health, education, violence, political power, human rights, war, poverty, inequality, energy, hunger, and humanity’s impact on the environment.

We can see in Table 1.6 that the USA is ranked 29th out of 167 on the democracy index, 20th out of 183 in relation to human rights, 46th out of 132 on government expenditure, and 45th out of 45 in relation to income inequality (the Gini coefficient). These rankings for the USA present similar results and measures to those highlighted above and paint a portrait of a nation-state with serious and, in many cases, exceptionally significant social injustice, despite, paradoxically, a comparatively large wealth-base (for the GDP per capita, the USA is ranked 8th out of 168). Similarly, the health indicators for the USA are also concerning and seemingly disconnected from the status of a wealthy country: 54/201 for the child mortality rate, 68/237 for life expectancy, 78/84 for the suicide rate. With regards to the environment, the USA ranks 204 out of 214 for per capita CO₂ emissions and is near the bottom of the OECD countries in the Environmental Performance Index. The multiple and significant inequalities we observe in the data could be partially explained by a lack of investments in education and in social and health services by respective governments to guarantee access to similar services for all society. The USA is ranked 46th out of 132 countries in terms of Government expenditure (% of GDP) in these areas, far behind countries such as France (2nd/132), Finland (5th/132) or Germany (8th/132), which all obtained better results in terms of equity.

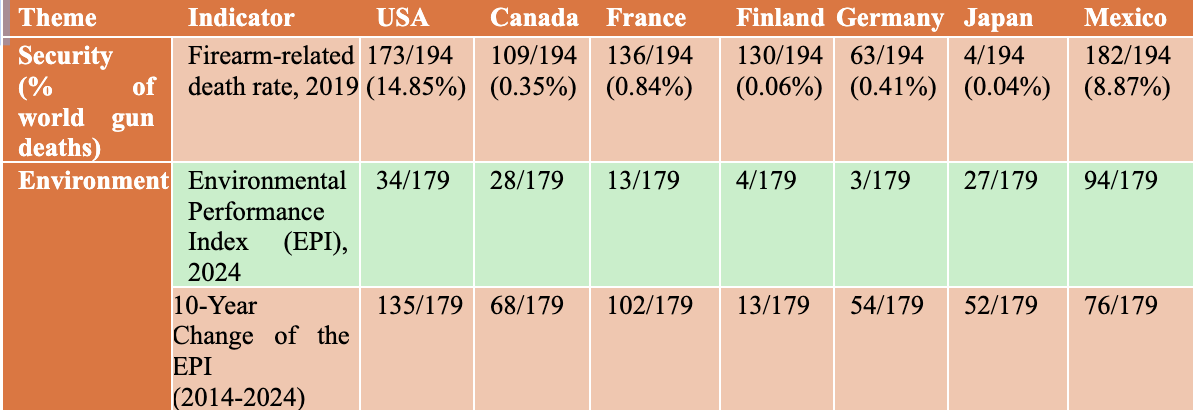

According to its website, “WorldPopulationReview.com is an independent for-profit organization committed to delivering up-to-date global population data and demographics”. Using its dataset (World Population Review, 2024), within the countries that are compared, except for Mexico, the United States scored extremely poorly in terms of security, Firearm-related death rate (173rd/194). For the social inequality index, based on the Gini Coefficient, the USA also places at the bottom of OECD countries, comparatively lower than the overall country portrait.

Another database is Statista, and it also provides a range of indicators useful for this text.

Statista is a global data and business intelligence platform with an extensive collection of statistics, reports, and insights on over 80,000 topics from 22,500 sources in 170 industries. Established in Germany in 2007, Statista operates in 13 locations worldwide and employs around 1,100 professionals.Empowering people with data. Our pursuit of knowledge and innovation drives us to be thought leaders in the field. As pioneers in shaping the future of the data economy, our ultimate goal is to create a world that is more transparent, reliable, and trustworthy. We strive to empower fact-based decision-making that positively impacts society.

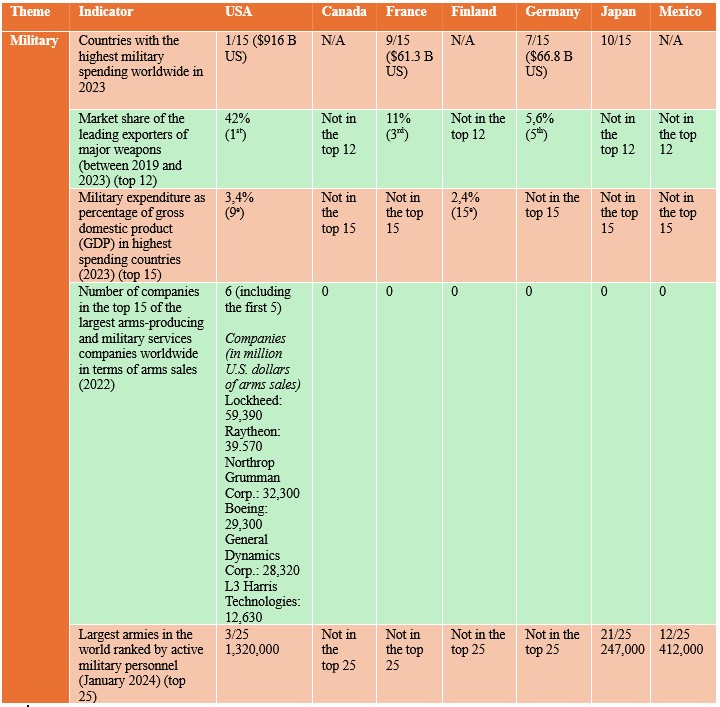

Notably, Statista highlights the USA’s vast and overwhelming military presence. Its expenditure on militarization (by far the largest, surpassing the next several countries together), especially considering all the diverse and serious problems that exist within its borders, is almost incomprehensible. The need to sustain roughly 750 military bases in around 70 countries, all the while engaging in numerous and diverse conflicts, overtly and covertly, speaks to the need to be perceived and to act like an Empire (Hussein & Haddad, 2021; O’Dell, 2023). Yet, the disproportionate emphasis on militarizing society and the world comes with an enormous cost in terms of political, economic, socio-cultural and moral dimensions (Hussein & Haddad, 2021). Johnson (2023) calculates that the “Average US taxpayer contributed more to militarism than Medicare in 2023”. We can also see how the USA is massively vested in meshing its politics and economics with the military project, with many of its companies dominating the worldwide arms trade.

In relation to the environment, the portrait is not positive is for the Environmental Performance Index (EPI) (34th/179), and it had one of the worst rankings amongst all countries in the “developed” world for 10-Year Change of the Environmental Performance Index (2014-2024) (135th/179).

Palley (2024, p. 1) frames the problematic nature of the military-industrial complex (MIC) as a threat to democracy.

Understanding the MIC is critical to understanding contemporary US capitalism, US international policy, and the drift toward Cold War II. The MIC exerts a massive societal impact. It twists economic activity toward military spending; twists the character of technical progress; is socially corrosive via its capture of politics and government; twists societal understanding of geopolitics to increase demand for war services; promotes militarism and increases the likelihood of war; and promotes proto-fascist drift because militarism drips back into national politics. Given those features, the MIC is of first-order significance and the consequences of failure to understand it are likely to be grim.

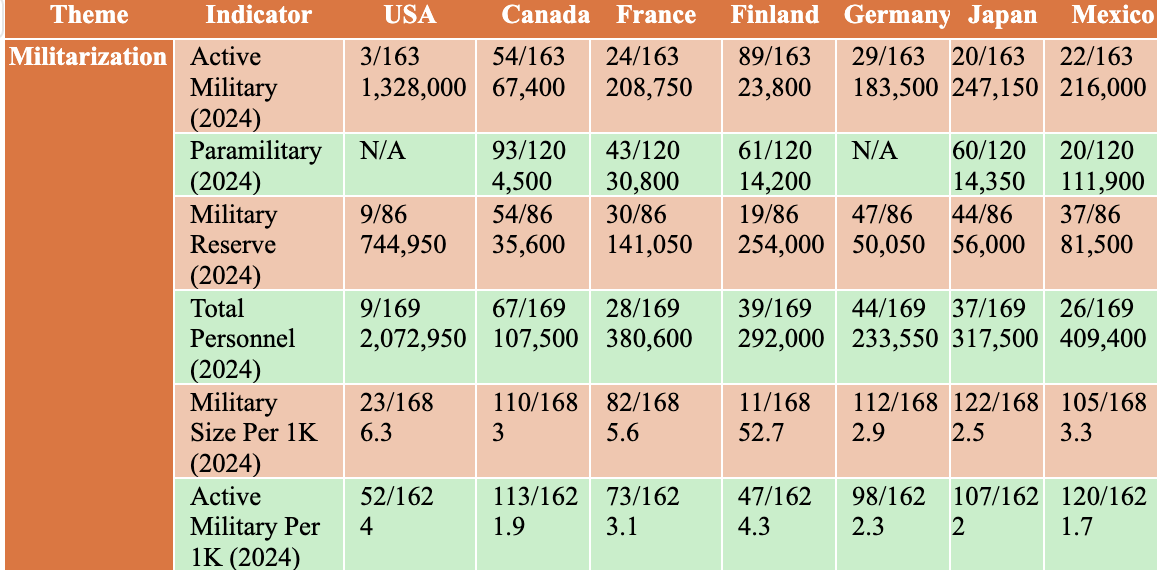

The incessant and seemingly permanent militarization of society at all levels feeds into the Pygmalion paradox, in which there is vigorous, generalized and uncritical support for the military (Malone, 2021), regardless of the costs, the sense or the impact, not to mention the prospects of a potential peace industrial complex being developed (Carr, 2022). Table 1.9, presenting Our World in Data indicators, highlights the USA’s disproportionate focus on militarization.

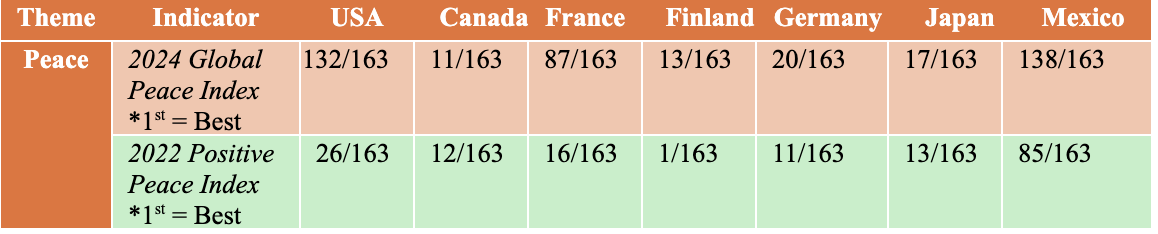

I am aware that some people may argue that a strong military leads to peace but I am not convinced, and, significantly, it would appear that a large percentage of the military venture, through infrastructure, research, space exploration, feeding profit-based companies, undergirding dictatorships, preparing troops and the actual work of invading countries, is far from a democratic enterprise. Table 1.10 provides a portrait of the Vision of Humanity dataset that places the USA within an unfavorable comparative position (132nd place out of 163 on the Global Peace Index).

In sum, to wrap up this section of the chapter, it is worth stressing that the USA is not the best, the most complete, the most democratic or the “greatest” nation. There simply is not one best, most complete, most democratic, “greatest” nation. All nation-states have problems, and we can see through this assembling of the diverse data-points, studies and rankings above that many people around the world are not positively included in the democracy equation. At the very least, there are many people who are marginalized, disaffected, fragilized and victimized in the name of democracy. These power imbalances do not fluidly favor the eradication of poverty, discrimination and social inequalities. Moreover, we can also legitimately ask: what democracy, for whom, how, and to what end? It is clear that the USA is facing multiple problems and challenges—and, by no means, I am not inferring that Canada and other countries have found the solution to social inequality—, and the Pygmalion discourse is likely to uphold the false consciousness that somehow everything is working well, that there is unity in the country. The normative narrative on democracy can delude and diminish the true representation of reality and also can affect meaningful efforts to achieve substantive social change.

Some thoughts on elections and democracy

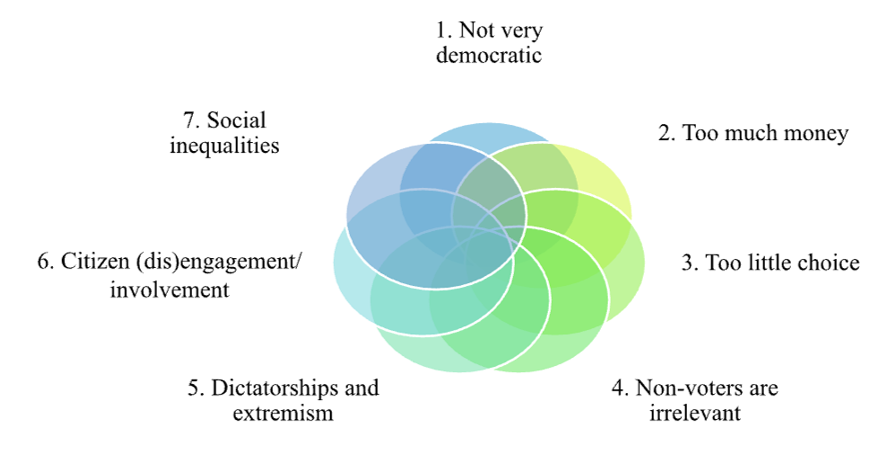

Starting to write this chapter days before the 2024 Presidential Election is an unusual experience. Every election has its foibles and flaws but this one, as alluded to above, is, so to speak, one for the ages. In the past week, one of the two candidates—since the mainstream media only profiles the leaders of the Democratic and Republican parties, feigning that no other options do or should exist—held a forty-minute dance party at a rally, served French fries at a McDonald’s drive-through window, drove a garbage truck with a security vest on to extol his proximity to the working class, and proclaimed his natural and tangible connection to, and the list is extremely long, women, Blacks, Latinos, working people and many other groups; and this is after claiming that Haitian immigrants were eating people’s pets in Springfield, Ohio. The other side has been busy producing claims, affirmations, insinuations, negative ads and the like with a barrage of counteractions. There is literally a ton of polling and minute-by-minute prognostications. As suggested earlier, this is a very long-winded, costly and arduous affair. Populism is liberally slathered within the process, and its effects can be profoundly deleterious (Yilmaz & Morieson, 2022; Ruth-lovell & Grahn, 2023). Democracy is a messy business, and some might say that elections are not meant to be a clean, fluid, effortless exercise. In the figure below, I suggest that there are some serious problems with normative elections, building on a previous text (Carr, forthcoming).

I will briefly present each of the components in the figure above. To start, one might argue that the electoral system in the USA, and elsewhere, in general, is not that democratic. Elites have a disproportionate say in how systems, processes and policies are formulated, structured and implemented. The objective is principally to win, to beat the other candidates or parties, and not to build a democracy. On the contrary, constraining voters and votes can be a useful tactic or strategy. Importantly, there is a wide berth to accommodate extreme right-wing and even fascist participation in the process, as evidenced by the bevy of extremist parties that are inter-mingled within or close to power structures in a number of OECD countries at this time (Beauchamp, 2024). In many regards, a winner-take-all system has been created, one that can effectively discount, neutralize and diminish the supposed “checks and balances” or the “loyal opposition” (Turnball, 2023). The public service works for the party that has won the election, not for the people or society (although there is explicitly intended to be a government for the people). This means that the desire and quest to maintain power for the governing party pushes public servants and public services into a partisan and polemical quagmire, providing support, expertise and allegiance to a specific group of individuals, regardless of the known and unknown impact impacting society. In the USA, in particular, it is quite common for politicians elected and paid to act in one role to actively abdicate that position and campaign for another, all the while being remunerated for a job that they do not actively engage in. One cannot imagine a teacher, a professor, a nurse, a librarian, a public servant, anyone or any profession, supporting such a venture: logically, one might hear the refrain that you can take a leave of absence if you wish to campaign full-time for another position. There are also serious questions about gerrymandering, the carving up of electoral districts to eliminate some groups or areas or to favor others (Kirschenbaum & Li, 2023), attempts to restrict voting periods, with massive line-ups and logistical impediments, voting irregularities, and the injection of massive sums in the voting industry (machines, ballots, counting, litigation, etc.). Much of this anti-democratic behavior disproportionately affects communities of “color”. Lastly, the campaigns last an inordinate amount of time, and the question of cultivating meaningful dialogue has been replaced by rallies aimed at tearing down the proverbial “other guy”. In sum, election after election, it is difficult to ascertain, within the normative context, how democracy is uplifted and instilled within the body politic to address the real issues facing society, including the eradication of poverty, racism, corruption, warfare and the like (Turnball, 2023).

The second component in this problematization of normative elections concerns the overwhelming presence of money in the process (Al Jazeera, 2024). It is unclear why money is required to run a campaign or to get the message out, as there appears to be ample interest in the traditional (print, television, radio) media as well as newer, alternative and social media (podcasts, videos, websites, etc.). Since funds are or can be used, within the USA’s context, for negative advertising, television ads, marketing, polling, political advisors, signage, etc., one might ask if these are necessary expenditures, and, importantly, if they have any redeeming influence or impact on building a democracy. This funding is also used to suppress voter participation and advance legal maneuvers aimed at constraining engagement in the electoral process. Money injected into political parties and politicians’ hands can inevitably grease the wheel of corruption and compromised interests. Moreover, the disproportionate power dividends from this funding circle virtually eliminate the working class and marginalized sectors from the democratic equation. Increasingly, it would appear that billionaires are afforded a great voice, space and presence within the political processes, thereby influencing decision-makers to disproportionately move in the direction of their limited interests.

The third component echoes Noam Chomsky’s (1989) contention that vigorous debate is encouraged but must fit between strict parameters, thereby excluding alternative, radical and critical options and voices. Choice is, thus, extremely limited, and the generalized two-party system, the antithesis of choice, alternatives and vibrant democratic renewal (Drutman, 2021). The supposed peaceful, democratic transfer of power, one of the hallmarks of normative democracy between Republicans and Democrats in the USA, was put to the test with the January 2021 insurrection, framing the mob that stormed the Capitol in Washington. While passing formal power back and forth between the two main and legitimized political parties, as has been the case in Canada since its founding in 1867, can be seen as central to (normative) democracy, it also leads to a duopoly of shared interests, assets, control and capacity to further extend networks, relations and hegemony. Although there are many political parties in most countries, the vast majority are ignored, underplayed, discarded or blocked out, rendering them neutralized, and impeding them from central fora, debates and broad media coverage. Corporate interests are provided with overwhelming and disproportionate leverage to ensure, generally speaking, that only the two main parties are locked into the formal power center (Drutman, 2021). Of course, third parties do exist, and may even be able to mobilize significant support, in some instances, especially within proportional representation electoral systems in Europe, where coalitions are a common occurrence. Addressing longstanding and core problems, such as racism, poverty, reconciliation, etc., becomes extremely difficult after the main alternating political parties lock in support with their elite and traditional bases that may not view these important issues as meritorious of priority status.

The fourth component relates to the notion that non-voters are irrelevant, meaning people who do not vote are not considered a part of the process. Elsewhere (Carr, forthcoming), I outline some of the issues around this point.

Non-voters (Statistics Canada, 2022) are largely excluded in/from party platforms. In order to win, parties need to collect the votes of those supporting them. This involves fashioning policies, proposals and practices that appeal to people likely to vote for them. It also means that, for instance, if only 50% of eligible voters cast a vote, then to win the right to govern it may only require winning roughly a third of that block, effectively discounting the votes of the vast majority. Majority government in Canada is consistently formed with a relatively small percentage of voters, thus locking the control of government, ministries, funding, etc. into the hands of a small group. In sum, the processes of cultivating engagement are limited, and marginalized social classes/groups are considered liabilities. Would proportionate representation or other electoral reforms, including mandatory voting, enhance democracy? FAIR Canada[1] has sought to make the electoral process more legitimate and compelling, calling for a National Citizen’s Assembly on Electoral Reform. While potentially helpful, I question the legitimacy of winner-take-all elections as they discount all the pivotal issues outside of the central platforms and give the formal power basis to the winner without regard for all the other parties, interests and voters/non-voters.

The interests of the large non-voting block are effectively diminished throughout the electoral process, and this does not reinforce democratic engagement, participation and inclusion. Presumably, these potential voters also have concerns about society, but their voices are muted and considered expendable.

The fifth component relates to normative democratic support for dictatorships, which may seem counter-intuitive and anti-democratic but governments, notably in the USA but elsewhere as well, have historically played a significant role in overthrowing, destabilizing and installing dictatorial, anti-democratic regimes (Grandin & Denvir, 2023). When considering some of the indicators presented in the above section on the meaning of democracy, we can clearly see how militarization is infused within the normative democratic electoral project (Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, 2023), with war and conflict being a relatively acceptable part of governing. I previously framed this freneticism over permanent military engagement as follows (Carr, forthcoming):

The trend-line is going up, not down, even despite COVID-19; it is clear that the killing business has now reached its golden period, comfortably ensconced within normative democracy. Where would the world be today if the misguided and criminal US invasion of Iraq had not taken place in 2003 (Malone, 2021)? Of course, this is not a binary exercise, seeking to vilify only one country. On the country, many nations sustain a robust arms industry, including countries considered by some to be more peaceful, such as Canada, Sweden and Switzerland.

Perhaps the illustrative case of USA infiltration and hardwiring against democratic and left-wing regimes is in Latin America (Grandin & Denvir, 2023).

The sixth component concerns citizen (dis)engagement. Voting is not democracy, and the actual effort to do so is minimal despite the arduous, lengthy campaigns and untold sums of funding injected into the process. Voting is not a frequent event, although in Switzerland and some other jurisdictions, there might be the option to participate in referenda and specialized votes or consultations. Should we concern ourselves with why so many people do not vote (Rodriguez, 2020)? The drastic shift from mainstream to alternative and social media, although all the media exist concurrently and within diverse platforms and echo-chambers, can also provide us with a glimpse into how people may be engaged outside of the formal electoral process (Fujiwara et al., 2023; Hitchings-Hales & Calderwood, 2017). There are massive international as well as more targeted local social movements and untold other activities that underscore how engagement also needs to be understood outside of formal electoral processes. Governments, especially through schools, spend a great deal of time cultivating voting but this is a thin representation of the myriad ways that people can be engaged, and also how to seek and develop social change (Carr & Thésée, 2019).

The seventh and last component in this model, which is not intended to be comprehensive, underscores that, despite the normative electoral process, social inequalities are not sufficiently addressed. Again, elsewhere (Carr, forthcoming), I describe the importance of addressing longstanding inequality, and I conjecture that many people believe that a change in governing political parties within the normative electoral cycle is unlikely to provide expansive change.

Normative elections underpin normative democracy, and the pace of undoing generational poverty is not sufficiently addressed. Social mobility is limited, systemic, and institutional racism, sexism and xenophobia are dealt with in small measures/reforms that prevent broad inclusion. To be clear, there are many reforms, changes, movements, processes and people striving for change. This is the history of the world, that no matter how hopeless and debilitating a situation may be, many/most people always strive for some sense of meaning and emancipation. Is there room for agitation and mobilization within normative democracy? Without question, palpable tensions do exist, and marginalized groups do militate for significant social change. However, the normative electoral system can easily negate, diminish and/or obfuscate the prioritization of the needed social change (Swann & Yang, 2022). These elections are not suited to take on entrenched inequalities[2]. One might say that there are no alternatives, yet for those most directly impacted by inaction and marginalization, this cannot be a sufficient response. The relationship to/with the First Nations in Canada is but one example of the painfully slow pace of change (Midzain-Goban, 2021).

Thus, voting as a normative electoral process is problematic and comes with a number of provisos and concerns. The clear rise in the mobilization and electoral success of extreme right-wing parties is also clearly a concern.

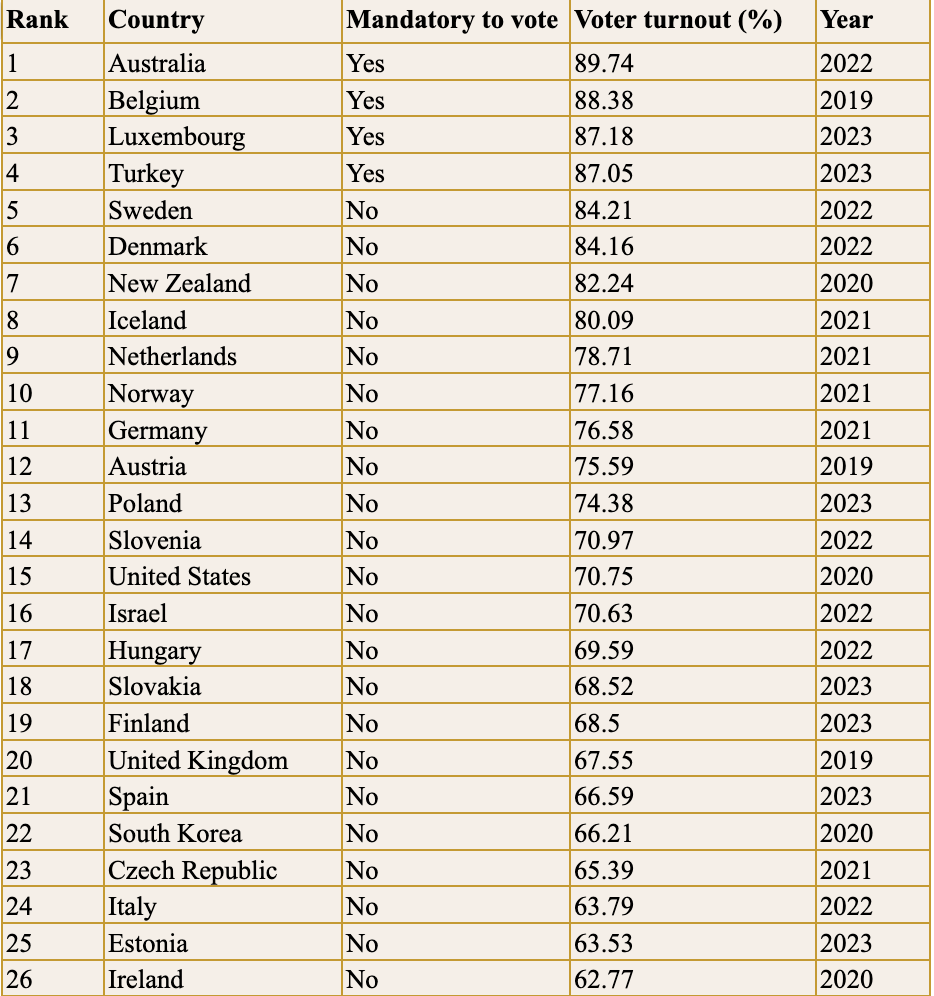

According to the World Population Review, we note in Table 1.11 that the USA ranks in 15th place for voter turnout, with roughly 30% of the eligible population not voting. It is also noteworthy that Canada has an even lower turnout, and that the participation rate, across the board, of the 18 to 25 age-range is a serious concern in OECD countries.

Reflecting on what it all means (to me)

This chapter has sought to present some of the issues, complexity and messiness with (normative and electoral) democracy. What is it, and how has it become so connected to elections and voting? Elections and voting can exist within a democracy, but should they eviscerate other forms of engagement, participation and agency? This is not a binary proposition but the question of the weight of normative elections is, I believe, an important one. I do vote during every municipal, provincial and federal election in Canada but I do not hold out complete hope that one party or the other will suddenly rectify the major issues that we are facing. However, we do need hope, not the joyous, jubilant, blind, and pollyannaish hope that will just materialize to make our lives better. We need hope that is hinged on solidarity, meaningful actions and an uplifting of social conditions and social representations that actually provide hope. Saying that we are hopeful, and then supporting dictatorships, conflicts, marginalization and racism can lead to disengagement from mainstream, normative democracy.

Building a democracy is an endless process, not an endpoint. Dissecting, problematizing and criticizing democracy is fundamental to achieving it. Claiming and proclaiming that we are democratic, even the “most democratic,” can be motivating or, conversely, delusional. The Pygmalion strategy of stating that we are the best is tantamount to pointing to the sky, hoping that people will be inspired by the imagery and boldness of the declaration. Or it might lead to a feeling of hopelessness for the multitudes of people who believe that their sustained reality is the contrary to hope. Hope may have concentric shapes emanating from the individual, with there being hope for a job, a place to live, happiness within the family, a vibrant community and social life, with peace close by, and, at the macro level, hope for a society without all the maledictions that we see and know.

Our singular voices can lead to engagement with others in our communities and societies. We might sometimes conclude that we can only change ourselves, not others, or that we see more hope in our own innovations and relationships and projects and passions. Paradoxically, we might participate in some formal, normative processes, such as elections, while working toward meaningful change at other levels. How we seek to transform democracy, to make it more democratic, engaged, inclusive and transformative requires a range of dialogues, processes and proposals. The creativity of the people can make our society more democratic, eliminating the elite money trap, antiquated electoral systems and decision-making regimes that hinge on political polarization and hyper-partisan entrenchment.

The introduction to this chapter alluded to the 2024 USA presidential election, and I will leave it to our colleagues writing the foreword and afterword in this book to make a connection with that pivotal event. I will only say, in conclusion, that this particular campaign significantly raised the bar on insults, lies, misrepresentations, scare tactics, threats, intimidation and hyperbolic posturing, all the while focusing on the worst or most problematic elements of a deformed and dysfunctional democracy: endless funding, attack-ads, polling, marketing, wedge-politics, personalized vilification and a dearth of substantive discussion of policies as opposed to a litany of false or exaggerated claims, many of which are racist, sexist and classist. And the months of diagnostics, prognostics and strategizing over, in and around the State of Pennsylvania is/was difficult to reconcile with the massive diversity inherent in a country of 350 million citizens.

I am, however, hopeful, in the Freirean sense of developing conscientization and solidarity, that people all over the place can mobilize despite the steamroller of electoral politics that often discards their meaningful desire for hope and engagement. And as for the USA, with all of its innovation, creativity and diversity of people, forming cultural manifestations that ultimately reach all corners of the world, I am hoping, in a very humble way, for more meshing of critically-engaged democracy from below to influence the nation-state above, thus tethering USA’s interaction/engagement with that of all of the other nations and peoples. Although there is an expansive discourse about unity in the USA, the country seems to be excessively fractured and divided at this time. The democracy we wish to live in is at our doorstep, but there is a maze between the welcome mat and the hallway welcoming us in.

References

Al Jazeera staff. (2024, October 31). Show us the money: How big money dominates the 2024 US election. Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/10/31/show-us-the-money-how-big-money-dominates-the-2024-us-election

Beauchamp, Z. (2024, July 17). Why the far right is surging all over the world: The “reactionary spirit” and the roots of the US authoritarian moment. Vox. https://www.vox.com/politics/361136/far-right-authoritarianism-germany-reactionary-spirit

Carr, P. R. (forthcoming). Does your vote (still) count? The poetics of elections in (normative) democracy. In George J. Sefa Dei & Manuel J. Ellul (Eds.), Critical Pedagogy and Social Justice: Major Challenges and the Way Ahead. New York: Peter Lang.

Carr, P. R. (2022). Insurrectional and Pandoran Democracy, Military Perversion and The Quest for Environmental Peace: The Last Frontiers of Ecopedagogy Before Us. In P. Jandrić, & D. R. Ford, (Eds.), Postdigital Ecopedagogies (pp. 77-92). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-97262-2_5

Carr, P. R. & Thésée, G. (2019). “It’s not education that scares me, it’s the educators…”: Is there still hope for democracy in education, and education for democracy?. Myers Education Press.

Chomsky, N. (1989). Necessary Illusions: Thought Control in Democratic Societies. South End Press. https://keimena11.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/noam_chomsky_necessary_illusions_thought_control_in_democratic_societies.pdf

Drutman L. (2021, June 16). Why The Two-Party System Is Effing Up U.S. Democracy. FiveThirtyEight. https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/why-the-two-party-system-is-wrecking-american-democracy/

Freedom House. (2024). Country and Territory. https://freedomhouse.org/countries/freedom-world/scores

Fujiwara, T., Müller, K., & Schwarz, C. (2023). The effect of social media on elections: Evidence from the United States. Journal of the European Economic Association, 22(3), 1495–1539. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeea/jvad058

Grandin, G., & Denvir, D. (2023). The United States has used Latin America as its imperial laboratory. Jacobin. https://jacobin.com/2023/03/greg-grandin-interview-us-policy-latin-america

Hitchings-Hales, J., & Calderwood, Imogen. (2017, August 23). 8 massive moments hashtag activism really, really worked. Global Citizen. https://www.globalcitizen.org/en/content/hashtag-activism-hashtag10-twitter-trends-dresslik/

Hussein, M. & Haddad, M. (2021, September 10). Infographic: US military presence around the world. Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/9/10/infographic-us-military-presence-around-the-world-interactive

Johnson, J. (2023, September 1). Average US taxpayer contributed more to militarism than Medicare in 2023: Report. Common Dreams. https://www.commondreams.org/news/us-taxpayers-funding-militarism

Kirschenbaum, J. & Li, M. (2023, June 9). Gerrymandering Explained. Brennan Center for Justice. https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/gerrymandering-explained

Malone, N. (2021). Why did so many Americans support the invasion of Iraq? Slate. https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2021/04/iraq-invasion-slow-burn-intro.html

Midzain-Gobin, L. (2021, September 6). Federal election: Canada’s next government should shift from reconciliation to decolonization and Indigenous self-determination. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/federal-election-canadas-next-government-should-shift-from-reconciliation-to-decolonization-and-indigenous-self-determination-166225

OECD. (2024). OECD Better Life Index. https://www.oecdbetterlifeindex.org/#/11111111111

O’Dell, H. (2023, October 25). The US is sending more troops to the Middle East. Where in the world are US military deployed? Bluemarble. https://globalaffairs.org/bluemarble/us-sending-more-troops-middle-east-where-world-are-us-military-deployed

Our World in Data. (2024). Democracy index, 2023. https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/democracy-index-eiu

Our World in Data. (2024). Human rights index, 2023. https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/human-rights-index-vdem

Our World in Data. (2024). GDP per capita, 2022. https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/gdp-per-capita-maddison

Our World in Data. (2023). Government spending as a share of GDP vs. GDP per capita, 2022. https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/government-spending-vs-gdp-per-capita

Our World in Data. (2023). Government expenditure (% of GDP), 2022. https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/government-spending-vs-gdp-per-capita

Our World in Data. (2024). Income inequality: Gini coefficient before and after tax, 2022: Income inequality. https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/inequality-of-incomes-before-and-after-taxes-and-transfers-scatter

Our World in Data. (2024). Homelessness rate, 2023. https://ourworldindata.org/homelessness

Our World in Data. (2023). Child mortality rate, 2021. https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/child-mortality?time=latest

Our World in Data. (2024). Life expectancy, 2023. https://ourworldindata.org/explorers/global-health?facet=none&Health+Area=Life+expectancy&Indicator=Life+expectancy+at+birth&Metric=Rate&Source=UN+IGME&country=OWID_WRL~CHN~ZAF~BRA~USA~GBR~IND~RWA

Our World in Data. (2024). Suicide rate, 2021. https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/suicide-rate-who-mdb

Our World in Data. (2023). Per capita CO₂ emissions, 2022. https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/co-emissions-per-capita

Our World in Data. (2023). Hours of work vs. GDP per capita, 1900 to 2000 (Absolute Change). https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/weekly-work-hours-vs-gdp-per-capita?tab=table&time=1900..latest&country=USA~CAN~FRA~DEU~SWE

Our World in Data. (2023). Hours of work vs. GDP per capita, 1870 to 2000. https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/weekly-work-hours-vs-gdp-per-capita?tab=table&time=1900..latest&country=USA~CAN~FRA~DEU~SWE

Our World in Data. (2023). Annual working hours per worker vs. GDP per capita, 2000 to 2017 (Absolute Change). https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/weekly-work-hours-vs-gdp-per-capita?country=USA~CAN~FRA~DEU~SWE

Our World in Data. (2023). Annual working hours per worker vs. GDP per capita, 2000 to 2017 (Relative Change). https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/weekly-work-hours-vs-gdp-per-capita?country=USA~CAN~FRA~DEU~SWE

Our World in Data. (2023). Annual working hours per worker, 2017. https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/weekly-work-hours-vs-gdp-per-capita?country=USA~CAN~FRA~DEU~SWE

Palley, T. (2024). The military-industrial complex as a variety of capitalism and threat to democracy: Rethinking the political economy of guns versus butter (Working Paper No. 2409). Post-Keynesian Economics Society. https://www.postkeynesian.net/downloads/working-papers/PKWP2409.pdf

Reporters Without Borders. (2024). 2024 World Press Freedom Index – journalism under political pressure. https://rsf.org/en/2024-world-press-freedom-index-journalism-under-political-pressure

Rodriguez, L. (2020, September 2). 5 reasons people in the US don’t vote. Global Citizen. https://www.globalcitizen.org/en/content/why-people-dont-vote/

Ruth-lovell, S. P., & Grahn, S. (2023). Threat or corrective to democracy? The relationship between populism and different models of democracy. European Journal of Political Research, 62(3), 677–698. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12564

Statista. (2024). Countries with the highest military spending worldwide in 2023. https://www.statista.com/statistics/262742/countries-with-the-highest-military-spending/

Statista. (2024). Largest armies in the world ranked by active military personnel as of January 2024. https://www.statista.com/statistics/264443/the-worlds-largest-armies-based-on-active-force-level/

Statista. (2024). Largest arms-producing and military services companies worldwide in 2022, by arms sales. https://www.statista.com/statistics/267160/sales-of-the-worlds-largest-arms-producing-and-military-services-companies/#:~:text=In%202022%2C%20Lockheed%20Martin%20was,followed%20on%20the%20places%20behind

Statista. (2024). Military expenditure as percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) in highest spending countries 2023. https://www.statista.com/statistics/266892/military-expenditure-as-percentage-of-gdp-in-highest-spending-countries/

Statista. (2024). Market share of the leading exporters of major weapons between 2019 and 2023, by country. https://www.statista.com/statistics/267131/market-share-of-the-leadings-exporters-of-conventional-weapons/

Swann, Cynthia A. & Yang, Elizabeth M. (2022). How inequality impacts voting behavior. Human Rights Magazine (American Bar Association), 48(1). https://www.americanbar.org/groups/crsj/publications/han_rights_magazine_home/economics-of-voting/how-inequality-impacts-voting-behavior/

The Economist Intelligence Unit. (2024). Democracy Index 2023: Age of conflict. The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited. https://www.protothema.gr/files/2024-02-15/Democracy-Index-2023-Final-report.pdf

Transparency International. (2024). Corruption Perceptions Index. https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2023

Turnbull, L. (2023, June 9). ‘Winner-take-all’ politics threatens Canadian democracy. Policy Options. https://policyoptions.irpp.org/magazines/june-2023/winner-take-all-politics/

Vision of Humanity. (2024). 2024 Global Peace Index. https://www.visionofhumanity.org/maps/#/

Vision of Humanity. (2024). 2022 Positive Peace Index. https://www.visionofhumanity.org/maps/positive-peace-index/#/

World Population Review. (2024). Countries with Mandatory Voting 2024. https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/countries-with-mandatory-voting

World Population Review. (2024). Environmental Performance Index by Country 2024. https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/environmental-performance-index-by-country

World Population Review. (2024). Gini Coefficient by Country 2024. https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/gini-coefficient-by-country

World Population Review. (2024). Gun Deaths by Country 2024. https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/gun-deaths-by-country

World Population Review. (2024) Military Size by Country 2024. https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/military-size-by-country

World Population Review. (2024). Voter Turnout by Country 2024. https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/voter-turnout-by-country

Yilmaz, I. et Morieson, N. (2022). Civilizational Populism Around the World. European Center for Populism Studies. https://doi.org/10.55271/pp0012

- See https://www.fairvote.ca/. ↵

- See Human Rights Watch at https://www.hrw.org/sitesearch?search=elections for a number of examples of how social inequalities and elections are intertwined. ↵