8. Using critical media literacy to examine our relationships with nature and democracy

Jeff Share

Abstract

This essay addresses the importance of an educational response to the climate crisis. While it does not suggest that education will solve global warming, it does take the position that education is essential for a progressive movement to counteract the increasing emissions of CO2 that are heating the planet and endangering life. Educators should encourage students to think critically about the stories they are hearing, seeing, and engaging with in the media daily. Once students learn to critically question the information and ideologies supporting an ego-logical worldview, they can be empowered to take action and create alternative media to challenge the injustices. Through critical media literacy pedagogy, educators can work with their students to examine the ways commercial media perpetuate environmental degradation. Critical media literacy empowers students to disrupt those harmful messages by creating their own ecological media messages with critical narratives of hope and action.

Keywords: critical media literacy, environmental justice, media education, ecomedia literacy, decolonization, biophilia, climate crisis, doctrine of discovery.

Résumé

Cet essai traite de l’importance d’une réponse éducative à la crise climatique. Bien qu’il ne suggère pas que l’éducation résoudra le problème du réchauffement climatique, il part du principe que l’éducation est essentielle pour un mouvement progressiste visant à contrer les émissions croissantes de CO2 qui réchauffent la planète et mettent la vie en danger. Les éducat·eur·rice·s devraient encourager les élèves à réfléchir de manière critique aux histoires qu’iels entendent, voient et avec lesquelles iels s’engagent quotidiennement dans les médias. Une fois que les élèves ont appris à remettre en question les informations et les idéologies qui soutiennent une vision du monde égo-logique, iels peuvent être en mesure d’agir et de créer des médias alternatifs pour lutter contre les injustices. Grâce à une pédagogie critique des médias, les éducat·eur·rice·s peuvent travailler avec leurs élèves pour examiner la manière dont les médias commerciaux perpétuent la dégradation de l’environnement. L’éducation critique aux médias permet aux élèves de perturber ces messages nocifs en créant leurs propres messages médiatiques écologiques par des récits critiques d’espoir et d’action.

Mots-clés : littératie médiatique critique, justice environnementale, éducation aux médias, éducation aux écomédias, décolonisation, biophilie, crise climatique, doctrine de la découverte.

Resumen

Este ensayo aborda la importancia de una respuesta educativa ante la crisis climática. Aunque no sugiere que la educación resolverá el calentamiento global, sí sostiene que la educación es esencial para un movimiento progresista que contrarreste las crecientes emisiones de CO2 que están calentando el planeta y poniendo en peligro la vida. Los educadores deben alentar a los estudiantes a pensar de manera crítica sobre las historias que escuchan, ven y con las que interactúan en los medios de comunicación a diario. Una vez que los estudiantes aprenden a cuestionar críticamente la información y las ideologías que respaldan una visión del mundo ego-lógica, pueden empoderarse para tomar medidas y crear medios alternativos que desafíen las injusticias. A través de la pedagogía de la alfabetización mediática crítica, los educadores pueden trabajar con sus estudiantes para examinar las formas en que los medios comerciales perpetúan la degradación ambiental. La alfabetización mediática crítica empodera a los estudiantes para interrumpir esos mensajes dañinos creando sus propios mensajes mediáticos ecológicos con narrativas críticas de esperanza y acción.

Palabras clave: alfabetización mediática crítica, justicia ambiental, educación mediática, alfabetización ecomediática, descolonización, biofilia, crisis climática, doctrina del descubrimiento.

Introduction

In a time of turmoil, when technology and climate are changing at an unprecedented pace and disinformation from science deniers continues derailing sustainable actions, we need to reconsider the ideologies, worldviews, and assumptions that are reproduced through the language we use and the stories we tell. This chapter explores ways humans have been separated from nature through the development of the Western worldview that treats the natural world as a resource to be used and exploited for the benefit of humans. This human-centric logic of domination over nature fits well with the economic model of capitalism but does not support a sustainable future for democracy, humanity, and all life on Earth.

While many solutions are needed to shift our unsustainable ideas and practices, this essay focuses on the potential of critical media literacy as an educational approach to promote critical thinking and empower educators and students to engage with social and environmental justice (Share, 2020). Students can build connections with the natural world as they learn about the ideologies and systems that have been, and continue to be, disconnecting people from each other and nature. This movement to recognize our interdependence with the natural world not only promotes a more sustainable future for humanity, but it is also necessary to build a robust, critically engaged democracy.

Critical media literacy is a pedagogical strategy that aims to develop the knowledge, skills, and dispositions to critically think, question, and act on the information and media that we engage with daily. We are living in the digital media age, in which an attention economy (Wu, 2019) and surveillance capitalism (Zuboff, 2019) are funding the social media, entertainment, and news information systems that connect us with and disconnect us from each other and the natural world. Information has become an extremely valuable commodity that the largest corporations in the world are competing for with the latest technology and marketing strategies. Under global capitalism and with information communication technologies that are designed to maximize profits over people, corporations are extracting our personal data with the strategic purpose of better targeting us with advertisements and propaganda to influence consumption and manipulate behavior.

Now more than ever, educators should be encouraging students to critically question dominant ideologies, challenge problematic representations, and create their own alternative media texts. Critical pedagogues, like Paulo Freire and Donaldo Macedo (1987), argue for the need to “read the word and the world.” Through critically using language and literacy to engage with media and each other, students can become active global citizens who can transform society and shape democracy. While it is problematic to suggest one problem is more important than any other of the grave challenges we are facing around the world, it is essential to recognize the growing impact of the climate crisis.

The climate crisis

According to the sixth assessment report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the international scientific community warns that there is no more serious problem than the climate crisis (IPCC, 2023). Extreme temperatures in the oceans and on land are breaking records now more than ever. From the Amazon to the Arctic, places that once were carbon sinks are now emitting more carbon dioxide than they are absorbing. As a result, global warming has become a climate catastrophe that affects everyone, but not equally. Human-caused climate change heats the atmosphere, acidifies the oceans, and erodes the lands with droughts, floods, fires, and extreme weather events. It is also triggering feedback loops that are intensifying the impact and creating domino effects (McKibben, 2011; Melton, 2019; Ripple et al., 2023).

Accompanying these devastating effects is a disinformation campaign largely funded by the fossil fuel industry to keep people from taking action and changing destructive policies and practices. Since the 1970s, scientists have been warning about the dangers of greenhouse gases, but those messages have been drowned out by political conservatism and well-funded fossil fuel campaigns designed to deny the facts, create doubt about the science, overwhelm people with climate doom, and delay any actions that could threaten their profits (McMullen, 2022; Oreskes & Conway, 2010; Osaka, 2023). When we consider the power of our media and political leaders to inform the public with science and advocacy or mislead the masses with propaganda and apathy, the role of critical media literacy is essential.

This is, therefore, a crucial moment for teachers to guide their students to think critically about the information and media that are promoting an anthropocentric (ego-logical) unsustainable exploitation of nature (López, 2021). Students can resist this dominant narrative by developing an ecological understanding of our interdependence with the natural world and becoming empowered to challenge the misleading and harmful discourses. The movement from an ego-logical to an ecological worldview opens new possibilities to build a future that is more sustainable, caring, and just.

The power of media and language

A key idea behind critical media literacy is understanding the power of media and language to shape thoughts and influence society. One example can be seen when Frank Luntz advised the George Bush Administration to change the language they were using to refer to the heating of the planet. Luntz (2003) asserted that “‘[c]limate change’ is less frightening than ‘global warming’” (p. 142). George Lakoff (2010) explains, “[t]he idea was that ‘climate’ had a nice connotation—more swaying palm trees and less flooded coastal cities. ‘Change’ left out any human cause of the change. Climate just changed. No one to blame” (p. 71). This successful substitution of words weakened the seriousness of the public climate discussion and contributed to delaying mitigating actions. A switch in language can lead to a shift in thinking and a change in action. To challenge this disingenuous use of language and provide a more accurate description of the situation, in 2019, the Guardian newspaper changed their style guide to no longer use the words “climate change” and instead refer to the problem as a “climate emergency” or “climate crisis” (Carrington, 2019). During the heatwaves in the summer of 2023, the UN Secretary General António Guterres made a similar linguistic move and asserted that “the era of global warming has ended; the era of global boiling has arrived” (Niranjan, 2023). The change from “climate change” to “climate crisis” and from “global warming” to “global boiling” are strategic counter-hegemonic uses of language intended to convey the gravity of the climate emergency.

The choice of words to describe, explain, or frame an idea influences the way people think about it. Lakoff (2004) refers to this as framing, and states that language evokes ideas and creates the frames that position people on how to think about an issue. He explains that frames “force a certain logic. To be accepted, the truth must fit people’s frames. If the facts do not fit a frame, the frame stays and the facts bounce off” (p. 15). Words, grammar, codes, and conventions of print, digital, visual, aural, and multimedia are the building blocks of communication that are framed by worldviews, values, and ideologies.

An insightful language lesson involves questioning the way pronouns can separate us from the natural world by referring to anything that is not human as an object with the pronoun “it.” Once a tree, river, or animal is objectified as an “it,” instead of being referred to as he/she/they, we are more likely to abuse or mistreat them. Robin Kimmerer (2017) asserts that “we use it to distance ourselves, to set others outside our circle of moral consideration, creating hierarchies of difference that justify our actions—so we don’t feel.” This use of pronouns to include or exclude can function to connect humans with nature as relatives or disconnect us and make it easier to exploit nature as a resource (Four Arrows, 2018). Since people are more likely to protect what they love, increasing our connections and biophilia (a love of nature) can be an important step in the process of confronting the climate crisis as active agents of change.

Another example of the role that grammar can play can be seen in the use of passive voice versus active voice, as the grammatical structure can shift the role of blame and responsibility. Consider the difference of the passive voice statement, “the climate is heating” compared to the active voice, “humans are heating the climate.” Journalists often use passive voice when reporting on climate change, male violence against women, and when they do not want the audience to think about the perpetrator (Frazer & Miller, 2009). An example can be seen in the way the New York Times reported on the US bombing of an Afghan hospital. In their headline, they used passive voice to describe a fact without naming the culprit: “Afghan hospital hit by airstrike, Pentagon says” (Norton, 2015). During the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020, many US newspapers printed headlines such as: “A photographer was shot in the eye,” with no attribution to the police who shot the photographer (Sitar, 2020). On the other hand, when journalists want to place blame on a group they do not align with, they will often report in the active voice and name the subject of the action, such as: “Protestors struck a journalist with his own microphone” (Sitar, 2020). The choice of passive or active voice frames the issue and positions the audience for how to think about the information.

Making matters worse, US media rarely mention climate change or global warming. In their report, “A Glaring Absence: The Climate Crisis is Virtually Nonexistent in Scripted Entertainment,” researchers reviewed 37,453 film and television scripts written during 2016 – 2020 and found only 2.8% of scripts included any of their 36 keywords related to climate change, and only 0.6% mentioned the words “climate change” (Giaccardi et al., 2022). Another investigation found that in 2021, the four major US TV news networks reported on climate change during only 1.2% of their overall news programming (MacDonald, 2022). During 2023, the hottest year on record, US commercial media, “ABC, CBS, NBC, and Fox Broadcasting Co. – scaled back their climate coverage by 25%” (Cooper, 2024). Not only is the climate crisis seldom mentioned in mainstream media, but on the rare occasion when they do report on global warming, they tend to prioritize extreme weather events, especially when they occur in Europe or North America. This focus on sensational climate events affecting White people often marginalizes or ignores the climate effects and slow violence impacting People of Color, island nations, and much of the Southern Hemisphere (Nixon, 2011).

It is also common for commercial news media not to mention any connection between severe weather events and global warming. During the rampant wildfires in Canada that were turning skies orange in New England, Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting (FAIR) conducted a review of broadcasts from the six major US news stations between June 5-9, 2023 (Riggio, 2023). Riggio (2023) states that “on US TV news, viewers were more likely to hear climate denial than reporting that made the essential connection between fossil fuel consumption and worsening wildfires—if they heard mention of climate change at all.” Of the 115 news segments that reported about the forest fires, only 44 (38%) mentioned any connection to climate change, and only 7 (6%) segments alluded to fossil fuels as a primary cause of the climate crisis. When a meteorologist for the TV news station KCCI in Des Moines, Iowa, Chris Gloninger, reported on the connections between extreme weather and climate change, he was harassed by so many hostile emails and a death threat that he ended up quitting his job (Wu, 2023). While the influence of dominant US corporate media is often overwhelming and influences people around the world, it is not absolute, making it important to recognize the power in challenging mainstream narratives and creating alternative media messages.

Environmental justice with university students

Exploring the ways media frame the public discourse and promote connections and/or disconnections with the natural world is the goal of a university environmental justice course based on critical media literacy. This is a class the author created and teaches at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) to undergraduate students in the School of Education. The course focuses on the power of stories, language, and media to frame the dominant narrative, shape our ideas about what is considered “normal,” and ultimately influence policies and practices.

While the course addresses some of the science behind global warming and the feedback loops that are triggering various ecological disasters, most of the class is spent focusing on the narratives about the climate crisis that are based on social and cultural practices. Once we recognize that humans already have the technology, money, and ability to stop adding greenhouse gases to the atmosphere if we choose to do so, then we can understand that our current climate crisis is more an issue of priorities and values than it is about science. This is not to suggest that change will be easy or that science is not important, instead it is an attempt to address our beliefs and assumptions, and the way media shape our ideas and influence our thoughts about what is and is not possible.

The climate crisis is not just a problem for the hard sciences, it is also a problem for the social sciences because communication, economics, and politics are playing powerful roles in how we respond to science. Author Rebecca Solnit (2023a) argues for the importance of recognizing that “what is unlikely is possible, just as what is likely is not inevitable” (p. 6). In many ways, it is the educators who teach language and literacy who have an ideal location to critically engage their students with the discourses that shape our relationships with the natural world. For this reason, we use critical media literacy to guide our theory and practice for teaching environmental justice.

Critical media literacy pedagogy

Critical Media Literacy is a pedagogical approach based on theories from cultural studies (Durham & Kellner, 2002; Hammer & Kellner, 2009) and critical pedagogy (Darder et al., 2003; Freire, 2010; Kincheloe, 2007) that aims to expand our understanding of literacy to include all types of texts, such as photographs, movies, music, social media, advertisements, memes, algorithms, as well as books, and deepen literacy instruction to critically question the way information and power are connected and never neutral. Critical media literacy involves teaching three dimensions: 1) knowledge of how systems, structures, and ideologies reproduce hierarchies of power and knowledge concerning race, class, gender, sexuality, and other forms of identity and environmental justice, as well as a general understanding of how media and communication function; 2) literacy skills to think critically, question media representations and biases, deconstruct and reconstruct media texts, and use a variety of media to access, analyze, evaluate, and create; and 3) a disposition for critical engagement with the world, leading to a desire to take action to challenge and transform society to be more socially and environmentally just. This third dimension is based on Paulo Freire’s (2010) notion of conscientização, a revolutionary critical consciousness that involves perception as well as action against oppression. These three elements can be transformative when taught through a democratic inquiry-based pedagogy that combines analysis and production for students to learn through creating media.

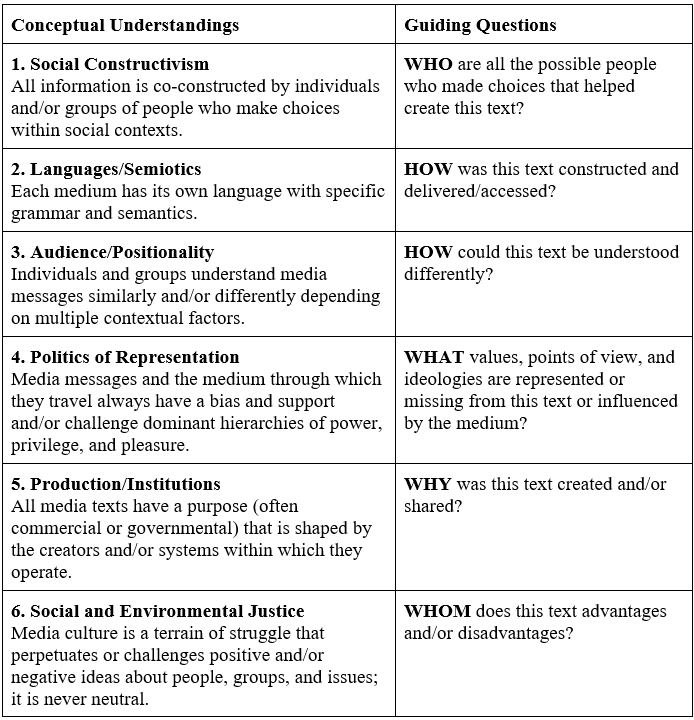

The following critical media literacy framework can be a useful tool for educators, providing six conceptual understandings to help them plan their lessons and guide their students in critical inquiry. The guiding questions provide the tools of inquiry for students to ask and answer questions that are designed to lead them to conceptual understandings (see Table 8.1).

The critical media literacy framework and pedagogy are intended to help educators guide their students in critical inquiry to better understand society and themselves. Livingstone (2018) asserts, “media literacy is needed not only to engage with the media but to engage with society through the media.” This type of critical engagement is essential for a robust democracy. When we consider the dominant ego-logical relationship with nature that is most common in Western culture, it is important to explore how it has evolved and what forces have influenced systems, structures, policies, and worldviews.

The doctrine of discovery

To gain a better understanding of the systems and structures that have been disconnecting humans from nature, it can be helpful to look historically at some of the major changes that have occurred since the time when most humans lived sustainably with the environment and considered nature sacred. While many Indigenous communities around the globe continue to live in balance with the natural world through preserving their ancient traditional ecological knowledge that has evolved over thousands of years, the Modern Era of global capitalism has developed a different worldview that treats nature as a resource for the extraction and exploitation of humans. Carolyn Merchant (1989) writes, in 17th-century Europe, “[t]he metaphor of the earth as a nurturing mother was gradually to vanish as a dominant image as the Scientific Revolution proceeded to mechanize and to rationalize the world view” (p. 2).

The separation and domination of humans over nature were the result of many factors, from ideas and inventions that emerged during the “Age of Enlightenment” to laws and beliefs that promoted colonialism and capitalism. In the 15th and 16th centuries, a series of Papal Bulls issued by the Vatican became known as the Doctrine of Discovery and acted as some of the first international laws to justify conquest and theft across the globe. In 1493, the year after Columbus landed in what became known as the Americas, Pope Alexander VI issued the Papal Bull “Inter Caetera” stating, “The Catholic faith and the Christian religion be exalted and be everywhere increased and spread, that the health of souls be cared for and that barbarous nations be overthrown and brought to the faith itself.” These religious edicts instructed the kingdoms of Europe to conquer, dominate, and take any resources from lands inhabited by non-Christians (therefore deemed empty land, “terra nullius”) once they “discovered” them (Miller, 2008). The Doctrine of Discovery became a guiding light for many founding fathers and colonial governments from Canada to Australia (Miller et al., 2012).

After seven years of funding the French and Indian War in North America, King George III of England was upset with the British colonists for wasting so much of his money and issued the Crown’s Royal Proclamation of 1763, in which three key mandates pushed the colonists closer to revolution. The King required taxes from the colonists, centralized control of all trade with the Native Americans, and created a boundary from the Appalachia and Allegheny Mountains that no British colonist was allowed to cross (Miller, 2012). These attempts by the Crown to control the colonists’ ability to purchase or take Indigenous lands were one of the concerns mentioned in the US Declaration of Independence. The founding fathers complained that the King was “raising the conditions of new Appropriations of Lands” and causing problems with the “merciless Indian Savages, whose known rule of warfare is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes, and conditions” (US, 1776). This clash over who could control the discovery rights of North America became much of the basis of the Articles of Confederation and the Louisiana Purchase. President Thomas Jefferson’s purpose for sending Lewis and Clark to explore the newly purchased land west of the Mississippi River was not simply to map the uncharted territory; it was, more importantly, to perform the rituals of the Doctrine of Discovery to solidify his discovery rights to the land.

In 1823, the Doctrine of Discovery was formalized into a legal principle when the US Supreme Court unanimously ruled in the case Johnson v. McIntosh (1823) that “discovery gave exclusive title to those who made it” (Miller, 2008, p. 52). In a dispute between two parties that had purchased the same Indian land, the side that bought the land from the Native people lost the case to the side that purchased the land from the federal government. This ruling referenced the 15th-century Papal Bull and denied Native Americans the legal right to own or sell their land, giving them only the right of occupancy, something the owner of the discovery right (the federal government) could extinguish.

This logic of domination over people and the natural world has become a legal practice and perspective embedded in Western ideology and global capitalism. After decades of protests from Indigenous communities, in March 2023, the Vatican finally issued an official repudiation of the Doctrine of Discovery. However, the legal precedent of the Doctrine of Discovery is still cited in legal battles, such as in the case of White vs. University of California (2014) in which anthropologists from the University of California, Los Angeles “discovered” a double burial site at the University of California, San Diego, with two human skeletons about one thousand years old (the earliest known human remains from N. or S. America). The land where they were found was originally occupied by the Kumeyaay Nation which consists of several federally recognized Indian tribes. When the university refused to repatriate the bones to the Indigenous ancestors, a legal battle ensued in which the University of California lawyers referenced the Doctrine of Discovery to support their case to keep the bones. This law is just one example of how the policies, media messages, and ideologies of domination, appropriation, extraction, and exploitation continue to promote unjust and unsustainable ideas and practices that disconnect people from nature.

The Doctrine of Discovery is also an example of the ego-logical worldview of domination over nature and humans. This perspective demonstrates the intersections of racism and environmental exploitation. Hop Hopkins (2020) writes, “we will never survive the climate crisis without ending white supremacy. Here’s why: You can’t have climate change without sacrifice zones, and you can’t have sacrifice zones without disposable people, and you can’t have disposable people without racism.” White Supremacy is embedded in the Doctrine of Discovery that gave White Christians from Europe the legal and moral authority to decide who is disposable. With the support of Church and State, the European conquerors acted on their beliefs that they had the right and obligation to dominate nature and people who did not pray like them or look like them.

Rights of nature movement

To challenge this racist, colonial, and unsustainable ideology, students can look at the Rights of Nature Movement. This is a growing legal drive to impart personhood rights to the natural world, rejecting the logic of domination in favor of a perspective that values ecosystems such as the Whanganui River in New Zealand and manoomin wild rice in Minnesota (Surma, 2021).

While we can see countless examples of rights of nature in Indigenous communities around the globe, the origin of the legal battle is often attributed to Christopher Stone, a legal scholar at the University of Southern California who published an article in 1972 titled, “Should Trees Have Standing? —Toward Legal Rights for Natural Objects.” In this essay, Stone argues that many groups of people, such as women, children, enslaved people, and various groups of People of Color who were once denied legal personhood rights and treated as objects, have now finally been granted legal rights of personhood. Using this logic, Stone argues it is time to consider giving personhood rights to parts of the natural world like we have already done to people deemed not fully human and non-human objects, such as trusts, corporations, municipalities, and even ships. Stone (1972) explains that in our legal system, the natural world is treated “as objects for man to conquer and master and use—in such a way as the law once looked upon ‘man’s’ relationships to African Negroes” (p. 463).

Another benefit of giving legal standing to nature, Stone explains, is that this could also lead to a change in public consciousness, to rethink our relationship with nature; potentially lessen our negative impact and increase our understanding of our interdependence with the natural world. Stone writes, “until the rightless thing receives its rights, we cannot see it as anything but a thing for the use of ‘us’ — those who are holding rights at the time” (p. 455). Historically, humans have had difficulty valuing things that do not have rights, “it is hard to see it and value it for itself until we can bring ourselves to give it ‘rights’” (p. 456).

His article published in the Southern California Law Review was cited in the dissenting opinion of US Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas in a case in which the Sierra Club was suing the US Secretary of the Interior to protect part of the Sierra Nevada Mountains from Disney’s plans to build a ski resort (Sierra Club v. Morton, 1972). While the Sierra Club did not win the case against Disney, the legal discussion about the rights of nature was ignited. In Stone’s obituary in the New York Times, several international legal scholars are quoted about the importance of Stone’s article in legal battles around the world, from New Zealand to India (Traub, 2021). To build public support for the rights of nature in New Zealand, Maori scholars James Morris and Jacinta Ruru (2010) write:

[latex]We argue that applying Stone’s idea to afford legal personality to New Zealand’s rivers would create an exciting link between the Maori legal system and the state legal system. The legal personality concept aligns with the Maori legal concept of a personified natural world. By regarding the river as having its own standing, the mana (authority) and mauri (life force) of the river would be recognised, and importantly, that river would be more likely to be regarded as a holistic being rather than a fragmented entity of flowing water, riverbed and riverbank. (p. 50)

The Rights of Nature Movement has spread across the globe. Since 2006, over 409 rights of nature initiatives have been filed in 39 countries (Putzer et al., 2022). In 2008, the country of Ecuador rewrote its national constitution and officially recognized the rights of nature. Similar initiatives are taking place around the world, including in the United States, in which individual states are fighting for Green Amendments to their state constitutions (van Rossum, 2022).

Critical media literacy to challenge the dominant narratives

Through incorporating critical media literacy with the rights of nature, educators can design lessons to help students understand our interdependence with the natural world while also learning about important legal movements. The critical media literacy framework encourages students to investigate under-representations by questioning whose voices are missing and whose perspectives are omitted from the dominant discourse. These questions can address the rights of nature when analyzing media representations that frame the environment as merely an object or resource to be acted upon. While bringing ideas into classrooms that challenge dominant narratives can be difficult and sometimes risky, continuing to teach to the test and ignore the climate crisis carries far greater risks for the entire planet.

As students unpack the anthropocentric narrative that dominates most commercial media, they can create alternative stories as they learn about a more ecological worldview regarding the interrelationships of all beings and ecosystems. Students can make their own media, such as books, movies, social media posts, and podcasts that use creativity and critical perspectives to promote the rights of nature. They can give voice to animals, plants, land, air, and water (Share & Beach, 2022). A wonderful potential of digital media is that it can easily be shared across the Internet, providing a global forum for students’ ideas. Students can see examples of short videos that are voiced by famous actors speaking on behalf of nature at Nature is Speaking on YouTube. When students create work for an audience beyond the teacher, motivation increases, and they learn firsthand about the power of media to be a tool for positive change.

There are countless possibilities for the types of messages students can create once they engage critically with the media that shape our beliefs and behaviors about our relationships with nature. Critical media literacy pedagogy can be a helpful tool for educators to guide their students to question and act on the ego-logical worldviews that frame so much of the media they engage with daily (López, 2021). When students are empowered to critically question and respond to the media messages they encounter, they gain the opportunity to participate in the democratic process and use the power of media to express their concerns and challenge the problems.

Conclusion

To address the climate crisis, we need a paradigm shift from our ego-logical beliefs in human domination over nature to a more ecological worldview that understands our interdependence with the natural world. It is time for new stories that can reframe our relationship with nature to connect us with each other and the more-than-human world through understanding, compassion, and hope (Römhild, 2023). A new framing of the climate crisis should be less about sensationalizing fear and spectacle and more about critically understanding science and promoting stewardship. Solnit (2023b) reminds us that “stories can give power – or they can take it away.” The stories we share and the words, images, and sounds we use matter because what we include or omit, and how we tell the stories, reflect our biases and position the audience for how they are more likely to respond.

The medium of communication always influences the content of the message, making neutral communication impossible and objective news reporting an unachievable goal. It is these biases, inherent in all communication, that are the reason educators need to do more than prepare students to just judge authenticity and, instead, learn how to critically question the construction, bias, context, intention, and effects of all media. When students are empowered with the knowledge, competencies, and disposition of critical media literacy, they can become leaders in the ecological movement to reconnect us with the natural world and build a more democratic, just, and sustainable future for everyone.

References

Carrington, D. (2019, May 17). Why the Guardian is changing the language it uses about the environment. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/may/17/why-the-guardian-is-changing-the-language-it-uses-about-the-environment

Cooper, E. (2024). How broadcast TV networks covered climate change in 2023. Media Matters for America. https://www.mediamatters.org/broadcast-networks/how-broadcast-tv-networks-covered-climate-change-2023

Darder, A., Baltodano, M., & Torres, R. D. (Eds.). (2003). The critical pedagogy reader. Routledge Falmer.

Durham, M. G., & Kellner, D. M. (Eds.). (2002). Media and cultural studies: KeyWorks. Blackwell.

Four Arrows (2018, December 15). Can adopting a complementary Indigenous perspective save us? Truthout.org. https://truthout.org/articles/can-adopting-a-complementary-indigenous-perspective-save-us/

Freire, P. (2010). Pedagogy of the oppressed (M. B. Ramos, Trans.). The Continuum International Publishing Group, Inc.

Freire, P., & Macedo, D. (1987). Literacy: Reading the word and the world. Bergin & Garvey.

Frazer, A. K., & Miller, M. D. (2009). Double standards in sentence structure: Passive voice in narratives describing domestic violence. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 28(1), 62-71. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927X08325883

Giaccardi, S., Rogers, A., & Rosenthal, E. L. (2022). A glaring absence: The climate crisis is virtually nonexistent in scripted entertainment. Norman Lear Center Media Impact Project, University of Southern California and Good Energy. https://www.mediaimpactproject.org/climateinentertainment.html

Hammer, R., & Kellner, D. (Eds.). (2009). Media/cultural studies: Critical approaches. Peter Lang.

Hopkins, H. (2020, June 8). Racism is killing the planet: The ideology of white supremacy leads the way toward disposable people and a disposable natural world. Sierra. https://www.sierraclub.org/sierra/racism-killing-planet?fbclid=IwAR1DmlS-iJCvWPqbb4KAl7PRNRfn3RuTTDf4YHPq-CTQkzoczXLyIX7_4J8#.Xt57OrLtHZR.facebook

IPCC (2023). Climate change 2023: Synthesis report. A Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, H. Lee and J. Romero (eds.)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland. https://www.ipcc.ch/assessment-report/ar6/

Kellner, D. & Share, J. (2019): The critical media literacy guide. Engaging media and transforming education. Brill.

Kimmerer, R. (2017) Speaking of nature: Finding language that affirms our kinship with the natural world. Orion Magazine. https://orionmagazine.org/article/speaking-of-nature/

Kincheloe, J. (2007). Critical pedagogy primer. Peter Lang.

Lakoff, G. (2004). Don’t think of an elephant! Know your values and frame the debate. Chelsea Green Publishing.

Lakoff, G. (2010). Why it matters how we frame the environment. Environmental Communication, 4(1), 70-81.

Livingstone, S. (2018, May 8). “Media literacy – Everyone’s favourite solution to the problems of regulation.” The London School of Political Science and Economics. https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/medialse/2018/05/08/media-literacy-everyones-favourite-solution-to-the-problems-of-regulation/

López, A. (2021). Ecomedia literacy: Integrating ecology into media education. New York, NY: Routledge.

Luntz, F. (2003). The environment: A cleaner, safer, healthier America. The Luntz Research Companies—straight talk (pp. 131-146). Unpublished Memo.

MacDonald, T. (2022, March 24). How broadcast TV networks covered climate change in 2021. Media Matters for America. https://www.mediamatters.org/broadcast-networks/how-broadcast-tv-networks-covered-climate-change-2021

McKibben, B. (2011). Eaarth: Making a life on a tough new planet. St. Martin’s Griffin.

McMullen, J. (Director). (2022, April 19). The power of big oil. [Film, three-part series]. Frontline. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/frontline/documentary/the-power-of-big-oil/#video-1

Melton, B. (2019, Feb. 3). Climate change in 2019: What have we learned from 2018? Truthout. https://truthout.org/articles/climate-change-in-2019-what-have-we-learned-from-2018/

Merchant, C. (1989). The death of nature: Women, ecology, and the scientific revolution. HarperOne.

Miller, R. J. (2008). Native America, discovered and conquered: Thomas Jefferson, Lewis and Clark, and manifest destiny. University of Nebraska Press.

Miller, R. J., Ruru, J., Behrendt, L., & Lindberg, T. (2012). Discovering Indigenous lands: The doctrine of discovery in the English colonies. Oxford University Press.

Morris, J. D. K., & Ruru, J. (2010). Giving voice to rivers: Legal personality as a vehicle for recognising Indigenous people’s relationships to water? Australian Indigenous Law Review, 14(2), 49-62. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26423181

Niranjan, A. (2023, July 27). ‘Era of global boiling has arrived,’ says UN chief as July set to be hottest month on record. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/science/2023/jul/27/scientists-july-world-hottest-month-record-climate-temperatures

Nixon, R., (2011). Slow violence and the environmentalism of the poor. Harvard University Press.

Norton, B. (2015, October 5). Media are blamed as US bombing of Afghan hospital is covered up. FAIR. https://fair.org/home/media-are-blamed-as-us-bombing-of-afghan-hospital-is-covered-up/

Oreskes, N., & Conway, E. (2010). Merchants of doubt: How a handful of scientists obscured the truth on issues from tobacco smoke to global warming. New York, NY: Bloomsbury Press.

Osaka, S. (2023, March 24). Why climate ‘doomers’ are replacing climate ‘deniers.’ Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/climate-environment/2023/03/24/climate-doomers-ipcc-un-report/

Putzer, A., Lambooy, T., Jeurissen, R., & Kim, E. (2022). Putting the rights of nature on the map. A quantitative analysis of rights of nature initiatives across the world, Journal of Maps, 18(1), 89-96.

Riggio, O. (2023, July 18). As skies turn orange, media still hesitate to mention what’s changing climate. Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting. https://fair.org/home/as-skies-turn-orange-media-still-hesitate-to-mention-whats-changing-climate/

Ripple, W. J., Wolf, C., Lenton, T. M., Gregg, J. W., Natali, S. M., Duffy, P. B., Rockström, J., & Schellnhuber, H. J. (2023). Many risky feedback loops amplify the need for climate action. One Earth, 6(2), 86-91. doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2023.01.004.

Römhild, R. (2023). Learning languages of hope and advocacy–human rights perspectives in language education for sustainable development. Human Rights Education Review.

Share, J. (2020): Critical media literacy and environmental justice. In W. G. Christ, & B. De Abreu. (Éds.), Media literacy in a disruptive media environment (pp. 283-295). Routledge.

Share, J., & Beach, R. (2022). Critical media literacy analysis and production for systems thinking about climate change. The Journal of Media Literacy – Research Symposium Issue. https://ic4ml.org/journal-article/critical-media-literacy-analysis-and-production-for-systems-thinking-about-climate-change/

Sierra Club v. Morton, 405 U.S. 727 (1972). https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/405/727/

Sitar, D. (2020, June 2). The New York Times was accused of siding with police because of ill-placed passive voice. Poynter. https://www.poynter.org/ethics-trust/2020/new-york-times-tweet-passive-voice/?fbclid=IwAR3heoz6g0tCIisKsT_QBCN5J4QUwnKhGmnyruUd5wZbovjY721o2kzj-y4

Solnit, R. (2023a). Difficult is not the same as impossible. In R. Solnit and T. Y. Lutunatabua (Eds.). Not too late: Changing the climate story from despair to possibility (pp. 3-10). Haymarket Books.

Solnit, R. (2023b, January 12). ‘If you win the popular imagination, you change the game’: Why we need new stories on climate. The Guardian Newspaper. https://www.theguardian.com/news/2023/jan/12/rebecca-solnit-climate-crisis-popular-imagination-why-we-need-new-stories

Stone, C. D. (1972). Should trees have standing? – Towards legal rights for natural objects. Southern California Law Review, 45, 450-501. https://iseethics.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/stone-christopher-d-should-trees-have-standing.pdf

Surma, K. (2021, Sept. 19). Does nature have rights? A burgeoning legal movement says rivers, forests and wildlife have standing, too. Inside Climate News. https://insideclimatenews.org/news/19092021/rights-of-nature-legal-movement/

Traub, A. (2021, May 28). Christopher Stone, who proposed legal rights for trees, dies at 83. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/28/us/christopher-stone-dead.html

US. (1776). Declaration of independence: A transcription. National Archives. https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs/declaration-transcript

Van Rossum, M. K. (2022, Aug. 5). Green amendments will empower environmental protection. Bloomberg Law. https://news.bloomberglaw.com/environment-and-energy/green-amendments-will-empower-environmental-protection

Wu, D. (2023, June 22). Meteorologist resigns, citing PTSD from threats over climate change coverage. Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2023/06/22/meteorologist-climate-death-threat-iowa/

Wu, T. (2019). Blind spot: The attention economy and the law, 82 ANTITRUST L. J. 771. https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/faculty_scholarship/2029

Zuboff, S. (2019). The age of surveillance capitalism: The fight for a human future at the new frontier of power. Public Affairs.