10. Framing democracy: The role of photography in shaping public discourse

Miranda McKee

Abstract

This essay delves into the transformative impact of the digital revolution on contemporary photography, emphasizing the unprecedented ease and ubiquity of visual storytelling through digital cameras, smartphones, and social media platforms. Within this context, the collective witnessing of injustice can prompt positive social change; however, the misrepresentation of marginalized individuals within this same medium can fuel racism, bigotry, and violence. As mis-and disinformation continues to plague digital communication platforms, the need for highly developed visual literacy skills becomes crucial, yet more attention should be devoted to thinking critically about the power of imagery. By examining visual rhetoric in mainstream media coverage of the pandemic, this essay scrutinizes instances of visual blame and racism within the COVID-19 visual coverage, revealing subtle and overt examples in mainstream media. The exploration extends to the ethical considerations surrounding the representation of death in photography, probing questions of dignity, trauma, and the responsibility of photographers, journalists, producers, publishers, and consumers. The digital turn has, in many ways, democratized image-making and publishing, offering the possibility of developing a new visual culture that champions social justice and solidarity. This chapter argues for the collective responsibility of society to foster ethical visual representation in news coverage, emphasizing the importance of visual literacy education and the need for a discerning audience that actively rejects misrepresentation.

Keywords: photography, visual literacy, social justice, social semiotics, photojournalism, pedagogy, digital revolution, representation.

Résumé

Cet essai se penche sur l’impact transformateur de la révolution numérique sur la photographie contemporaine, en soulignant la facilité et l’omniprésence sans précédent de la narration visuelle grâce aux appareils photo numériques, aux smartphones et aux plateformes de médias sociaux. Dans ce contexte, le témoignage collectif de l’injustice peut susciter un changement social positif; toutefois, la représentation erronée d’individus marginalisés dans ce même média peut alimenter le racisme, le sectarisme et la violence. Alors que la désinformation et la méprise continuent de sévir sur les plateformes de communication numérique, la nécessité d’acquérir des compétences hautement développées en matière de littératie visuelle devient cruciale, mais il convient d’accorder davantage d’attention à la réflexion critique sur le pouvoir de l’imagerie. En examinant la rhétorique visuelle dans la couverture médiatique de la pandémie, cet essai passe au crible les exemples de blâme visuel et de racisme dans la couverture visuelle du COVID-19, révélant des exemples subtils et manifestes dans les médias grand public. L’exploration s’étend aux considérations éthiques entourant la représentation de la mort dans la photographie, en sondant les questions de dignité, de traumatisme et de responsabilité des photographes, des journalistes, des product·eur·rice·s, des édit·eur·rice·s et des consommat·eur·rice·s. Le virage numérique a, à bien des égards, démocratisé la production et la publication d’images, offrant la possibilité de développer une nouvelle culture visuelle qui défend la justice sociale et la solidarité. Ce chapitre plaide en faveur de la responsabilité collective de la société pour favoriser une représentation visuelle éthique dans la couverture de l’actualité, en soulignant l’importance de l’éducation à la culture visuelle et la nécessité d’un public perspicace qui rejette activement les fausses représentations.

Mots-clés : photographie, alphabétisation visuelle, justice sociale, sémiotique sociale, photojournalisme, pédagogie, révolution numérique, représentation.

Resumen

Este ensayo profundiza en el impacto transformador de la revolución digital en la fotografía contemporánea, destacando la facilidad y ubicuidad sin precedentes de la narración visual a través de cámaras digitales, teléfonos inteligentes y plataformas de redes sociales. En este contexto, el testimonio colectivo de la injusticia puede impulsar un cambio social positivo; sin embargo, la mala representación de los individuos marginados dentro de este mismo medio puede alimentar el racismo, la intolerancia y la violencia. A medida que la desinformación y la malinformación continúan plagando las plataformas de comunicación digital, la necesidad de habilidades visuales altamente desarrolladas se vuelve crucial, aunque se debe prestar más atención a pensar críticamente sobre el poder de las imágenes. Al examinar la retórica visual en la cobertura mediática dominante de la pandemia, este ensayo analiza ejemplos de culpabilidad visual y racismo dentro de la cobertura visual del COVID-19, revelando ejemplos sutiles y evidentes en los medios de comunicación. La exploración se extiende a las consideraciones éticas en torno a la representación de la muerte en la fotografía, planteando preguntas sobre la dignidad, el trauma y la responsabilidad de los fotógrafos, periodistas, productores, editores y consumidores. El giro digital ha democratizado, en muchos sentidos, la creación y publicación de imágenes, ofreciendo la posibilidad de desarrollar una nueva cultura visual que promueva la justicia social y la solidaridad. Este capítulo aboga por la responsabilidad colectiva de la sociedad para fomentar una representación visual ética en la cobertura informativa, enfatizando la importancia de la educación en alfabetización visual y la necesidad de una audiencia crítica que rechace activamente la mala representación.

Palabras clave: fotografía, alfabetización visual, justicia social, semiótica social, fotoperiodismo, pedagogía, revolución digital, representación.

Introduction

Since its inception, photography has been a powerful tool for public pedagogy. The indexical nature of photography allows it to circumvent language barriers, delivering visual narratives from around the world while traversing the barriers of space and time. However, the act of photography is inherently subjective; every photograph is shaped by the cultural influences, beliefs, and biases of the photographer (Barthes, 1977; Berger, 1972). Reflecting on the work of Abigail Solomon-Godeau, Roger Simon reiterates, “…the politics of representation and the representation of politics cannot be separated from each other” (Giroux & Simon, 1994, p. 96). Despite their indexical nature, photographs should not be considered objective and instead are deeply influenced by the socio-cultural contexts from which they emerge. Knowing this, we must approach photographs critically, considering and being particularly wary of the hegemonic powers which may shape them.

Photographs play a crucial role in the democratic process. Digital technology has democratized the image-making and publishing process, extending visual storytelling beyond the grasp of gatekeepers and creating new avenues by which to champion social justice movements. Collective visual witnessing has, at times, catalyzed social action, as seen, for example, in response to police brutality in the United States (Treisman, 2021). However, the misrepresentation of marginalized individuals within this medium has also perpetuated racism, bigotry, and violence (Benjamin, 2019; Chun, 2018; Monea, 2022). Visual literacy skills play an essential role in navigating visual mis – and disinformation, which has become increasingly prominent when consuming content on social media platforms (Lyons et al., 2021). Yet, more attention should be dedicated to critically analyzing the power of imagery. In the era of digital communication, it is incredibly important to address the need for strong visual literacy skills to support citizens as they navigate misleading information online.

This chapter explores the role of visual literacy among citizens living within a democracy by examining the influence of social power dynamics on photographs circulating in mass media. As pointed out in Chapter 1, many countries that fall under the category of “flawed democracies,” including the United States, struggle with inequality as the elite portion of society maintains a disproportionate influence upon the systems that structure society. This abuse of power not only extends to influence the shaping of visual narratives which circulate in the press, but photographs in mass media can also work to reinforce such power imbalances. The text below examines the politics of visual representation while championing more inclusive visual narration. Through a multidisciplinary approach that integrates sociology, media studies, and political theory, this chapter explores the evolving landscape of visual democracy in the digital age.

Decoding Visual Representations and Ideologies in Photography Praxis

Representation matters. Recognizing the profound impact of imagery, Vicki Goldberg (1993) wrote, “Photographs have a swifter and more succinct impact than words, an impact that is instantaneous, visceral, and intense” (p. 7). Photographs wield significant influence over how we perceive and understand the world. However, as Douglas Kellner and Jeff Share (2019) cautioned, this potency carries the risk of an assumed objective truth, a belief reinforced by the prevalent understanding of photographs as evidential in legal and scientific contexts. While photographs help us explore and ‘know’ the world, each image is constructed within a specific socio-cultural framework (Berger, 1972). Rather than accepting photographs in the news as objective facts, Critical Theory encourages us to consider the cultural, historical, and ideological contexts within which this so-called ‘knowledge’ has been produced (Sensoy & DiAngelo, 2017).

Visual material circulating in mass media influences not only fashion trends, product purchases and lifestyle choices but also public perceptions, policy and political opinion. For instance, in the spring of 2020 – early in the pandemic and while various forms of lockdown were being exercised – a photograph of Newport Beach, California, was shot by photographer Mindy Schauer and published in the Orange County Register newspaper (Zhang, 2020). The image portrays a crowded beach, with sunbathers packed densely, filling the frame with more people than visible sand. The photograph sparked outrage, as it suggested the beachgoers were not following the social distancing recommendations, prompting California Governor Gavin Newsom to close all the beaches in Orange County, referring to the crowds as “disturbing” (Zhang, 2020). However, aerial footage captured on the same day at the same time revealed an entirely different reality: beachgoers were respecting social distancing measures and keeping a safe distance from one another (Zhang, 2020). The discrepancy between the two visual representations is not the result of photoshopping or generative AI but, instead, was the result of the photographer’s choice of camera lens. Schauer used a telephoto lens, known for compressing space, which produced a misleading image suggesting people were closer together than they were.

Ironically, the closure of the beaches in Orange County led to protests, with hundreds of citizens crowding together to voice their opposition, at that point not adhering to social distancing measures (Zhang, 2020). The photograph produced by Schauer not only misled the public but also likely influenced policy decisions while exacerbating political tensions. This story raises important questions: Did Schauer, a seasoned photojournalist with two decades of experience at the Orange County Register Newspaper, anticipate her photography’s impact once published? Was there an ulterior motive for using the telephoto lens? Was the use of the telephoto lens an intentional choice to produce a particular narrative? Moreover, how many viewers of the image understood the visual distortions that telephoto lenses can introduce? This section will explore the ways in which visual representations in photography are imbued with these underlying ideologies and how a critical approach can decode the complex layers of meaning embedded within photographic images.

In the process of composing an image, the photographer makes deliberate decisions regarding what elements are revealed or omitted from the frame. Whether undertaken consciously or subconsciously, these decisions are invariably shaped by the photographer’s value system. John Berger’s Ways of Seeing (1972) brought to broad BBC television audiences the practice of decoding visual art by examining the cultural influences that have shaped how people see one another from century to century. As an example, Berger unpacked the concept of the male gaze, demonstrating in paintings and other visual material how the female body has been portrayed, catering to heterosexual male desire. Berger’s work encouraged discourse among the participants in the show and simultaneously amongst viewers at home, challenging familiar visual tropes and fostering critical analysis of the motivations driving image creators. Learning from Berger, audiences are encouraged to ‘read’ visual imagery, considering the signs, symbols, and codes embedded within photographs and acknowledging visual material’s significant influence on our broader understanding of the world.

The more consistently that citizens are able to question the motivations driving imagery published within news reporting, the better armed they will be to decode the agendas designed to influence their political opinions. Successfully navigating this complexity necessitated a high level of visual literacy and media literacy more broadly—yet these skills are unevenly distributed and inconsistently developed across different populations. Misleading visual content can be created by staging, false captioning, and other manipulations, including AI-generated content, which is a more significant concern as of late. Like textual discourse, images encapsulate notions of power, representation, and identity in their content. Unfortunately, this exploitative legacy persists in the digital era. Wendy Hui Kyong Chun (2018) explains that machine learning algorithms continue to illustrate racial bias “…from ‘inadvertent’ and illegal discriminatory choices embedded in hiring software to biased risk profiles within terrorism-deterrence systems. These all highlighted the racism latent within seemingly objective systems, which, like money laundering, cleaned “crooked” data” (p. 64). Chun highlights a poignant example of racism materializing in the Google Photos application, where two black individuals were erroneously labelled as “gorillas” rather than being recognized as human beings (2018, p. 63).

We also see the impact of racist ideologies as they shape visual reporting in newspapers. Shatema Threadcraft (2017) writes about the untimely death and visual misrepresentation of Michael Brown, who was killed by a police officer in Ferguson, Missouri, in 2014. Threadcraft critiques the selection of photographs of Brown circulated in the media, such as an image of him wearing gold teeth and smoking, which were selected instead of other images of him, for example, smiling with family members. Threadcraft notes that a photo of Brown making a peace sign gesture was suggested in news coverage to signify gang symbology. Unfortunately, this was not an isolated incident. This pattern of misrepresentation reoccurred so frequently that the problem prompted the creation of the hashtag #IfTheyGunnedMeDown, which began to circulate on social media platforms. The prompt asked users, ‘what images would be featured if you were slain by police?’ while addressing the media bias when reporting on black death.

Threadcraft points out that in these cases, images are selected and published by the media, either consciously or unconsciously, in ways that attempt to justify the death of those portrayed by suggesting they were dangerous people. The work of bell hooks (2015) reminds us that white supremacy intersects with patriarchal hegemony, and Threadcraft extends this discussion to the emergence of another hashtag, #sayhername, which was created to draw attention to the underrecognized wrongful death of black women. These deaths tend to occur in private or domestic spaces rather than in public and publicly surveilled places. The underrepresentation, overrepresentation and misrepresentation of black bodies remains a significant problem under the broader societal issue of systemic racism, and visuals circulating in mainstream media play an important role.

As addressed by Paul Carr in Chapter 1, the uncritical support for the military-industrial complex in the United States raised significant concerns when evaluating the country as a healthy democracy. Visual content has long played a role in generating support for the U.S. military, with historical examples such as the poster of Uncle Sam looking sternly and pointing a finger at the viewer while exclaiming, “I want YOU for U.S. Army,” (Flagg, 1917) visually demanding immediate action. According to the Washington Post (Zenou, 2022), the 1986 movie Top Gun, featuring Hollywood heavy-hitter Tom Cruise, had a significant impact on recruitment for the Navy, featuring 1.8 million dollars’ worth of military support, including the use of a base, air fleet and Navy pilots. In return for this investment, the producers of the film agreed to edit the script, including the cancellation of the midair collision that was planned to kill off the main character’s friend and a shift of the love interest from a service member to a civilian to follow Navy regulations, which forbid such relationships. These are only a few of the numerous examples where imagery in pop culture has been used to promote the US military (Löfflmann, 2013). The concern here is regarding the use of emotive visual storytelling to promote political agendas and sway citizen perspectives.

Providing further perspective on the issue of funding in the United States, a retired Marine Corps sergeant named Thomas Brennan started The War Horse, which he describes as a non-profit newsroom that focuses on the human impact of military service. In a recent interview, Brennan emphasized the need to rethink what the country is asking of its service members, stressing that “it’s a vital part of the conversation that’s just missing and it’s even less present in the journalism ecosystem. Less than 5% of all journalism focuses on the military and national security, whereas…it’s our number one budget item” (Meyer, 2024, min. 25:03-25:30). He emphasized that more work must be done to bring important issues regarding the military to light, such as the toxic exposure endured by service members and funding cuts on suicide prevention care for those on active duty. Unfortunately, this kind of reporting does not get as much funding as films featuring Tom Cruise. The War Horse had to seek monetary support via a Kickstarter campaign and was born out of Brennan’s experience as the last full-time military reporter in North Carolina, which he pointed out is the second-largest Marine Corps base in the world.

While the recruitment poster was a very clear and direct advertisement for the US Military, films from Hollywood and photographs circulated in mass media present more subtle influences on public opinion. Visual propaganda like that identified in Top Gun glorifies the military, thereby lending itself toward public support of government funding while drawing attention away from other issues of concern, including the underfunded healthcare system in the United States. With a discerning eye toward visual critique, audiences might be better equipped to push back against the visual narratives which toe the line of an American Pygmalion democracy.

Unmasking Visual Narratives: Blame in COVID-19 Imagery

As a form of public pedagogy, photographs illustrate historically significant moments in politics and beyond, informing citizens about goings on both locally and globally. Photographs published by legacy media are paired with captions and embedded within text, adding a visceral component to the prose detailing each happening. Visuals presented in the news provide insight into pressing societal challenges, including the impacts of war, health emergencies, and the climate emergency, among other content. During COVID-19, for example, as various forms of lockdown encouraged people to stay home and away from others, citizens turned to mass media to learn more about the virus and its impact. Photographs, maps and infographics were presented early on during the crisis, offering a visual avenue through which citizens turned to understand the crisis better. As nations and institutions struggled to formulate guidelines, practices, and preventive measures, citizens were inundated with a vast array of visual data regarding COVID-19, ranging from accurate to misleading or outright false. Fake news, as we have come to know it, muddled the process of seeking accurate information online.

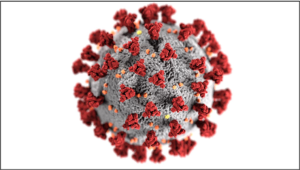

At the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, portraying the ‘invisible’ virus posed a significant challenge for news media outlets. Responding to this difficulty, the American Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) designed and released an illustration on January 29, 2020, that would become familiar to many, crafted by illustrators Alissa Eckert and Dan Higgins (see Figure 10.1 in the Appendix). In an article published in The New York Times (Giaimo, 2020), Eckert elaborated on the creative process behind the image, explaining that the illustration aimed to develop an identity for this threat, to bring “the unseeable into view” (Giaimo, 2020, para. 6). The illustrator explained that through the process of designing this image, the team hoped to emphasize the physical danger that the virus presented and its transmissibility via touch, which they addressed by designing the image of the virus with a visibly pronounced texture (Giaimo, 2020).

The interview also brought attention to another consideration: while Eckart described the color scheme, she explained that the illustration “was going to have to go along with the branding” (Giaimo, 2020, para. 15). The foreboding red spikes with tiny yellow and orange flecks could potentially connote caution, alarm, or perhaps blood to underscore the gravity of the disease. However, a lingering question remained regarding the nature of the ‘branding’ the illustrators were formulating, a point not expounded upon in the interview. Following the release of the illustration, its widespread use, in news coverage was facilitated by the CDC’s decision to make the image free to download and reproduce at a time when visual representations of the virus were scant. Subsequently, publications such as the Financial Times (Kynge et al., 2020) observed that the emergent COVID-19 ‘branding’ remarkably resonated with the imagery of the Communist Party of China’s flag, conveniently reinforcing Donald Trump’s ‘China-virus’ rhetoric (Kiely et al., 2020). The emphasis here is not to insinuate any complicity on the part of Eckhart or Higgins in a deliberate effort to target Communism or China but rather to underscore that the decisions made by two illustrators during a week-long ‘branding’ exercise could exert considerable influence on how the media eventually reports–and the public perceives–the ongoing pandemic.

The visual rhetoric that is observable in visual COVID-19 coverage that channeled misplaced blame toward certain marginalized groups manifested in both heavy-handed and less overt forms. For example, The Economist was called out on Twitter by activist Miqdaad Versi for a Twitter post which used COVID-19 news to perpetuate Islamophobia. The original post by The Economist stated, “The arrival of covid-19 was expected. The spread of radical Islam has been more of a surprise,” and was accompanied by an image of a woman in a black burka emerging from a shadowy doorway, captioned “Jihad is as contagious as covid-19 in the Maldives” (Versi, 2020, March 24). Versi retweeted the post, thereby creating a digital archive while stating:

Editors of @TheEconomist should be ashamed at themselves for allowing the magazine to be a platform where #COVID19 is exploited for bigotry

Whilst this specific tweet has now been quietly deleted

there’s no acknowledgement of the error nor an apology

Where’s the accountability? (Versi, 2020, March 24)

Other mainstream media outlets exercised a more subtle but equally concerning approach while presenting visual blame within COVID-19 visual coverage. On March 19, 2020, Global News Canada disseminated a video report highlighting a particularly dark moment as Italy’s death toll surpassed China’s (Balmer, 2020). In this video report (minute 1:46), the narrator explained that Australia and New Zealand were implementing measures to restrict the entry of foreigners to slow the spread of the virus. Notably, when the term ‘foreigners’ was uttered in the voice-over, the video concurrently featured footage of an airport with a woman wearing a chador walking into the frame. While anyone residing outside of these two island nations could be considered a ‘foreigner’, potentially carrying COVID-19 and presenting a risk to isolated populations, the news report visually directed negative attention toward a specific marginalized community. Against the backdrop of ongoing issues such as Asian hate and Islamophobia in Canada, where this news report emerged, publications that perpetuate these malicious narratives must be held accountable, whether the visual rhetoric is subtle or blatant.

The politics of visual representation can have a significant influence on public opinion. In the examples explored above, legacy media have taken advantage of their influential status to reinforce hegemonic narratives. Their position as long-standing and trusted sources of information provides a layer of authority that delivers an extended audience reach and also translates to a certain level of expected reliability, meaning citizens may not seek out secondary sources to verify content. However, the economic drive toward profitability, combined with the influence of political figures or parties, can direct content within these publications toward less-than-accurate reporting (Gasher et al., 2020). Reflecting upon the findings of Christopher Bail (2021) and others (Davis & Graham, 2021; Gaudette et al., 2021), it has become clear that social media platforms are designed to prioritize and reward extreme content, which leads to higher engagement. This propensity for high engagement not only fosters prolonged screen time for heated debates in the comments section but also exposes users to more advertisements, thus driving the platform’s revenue. While dialogue, both on and off social media, is vital for a healthy democracy, contemporary social media algorithms prioritize extreme content and polarizing interactions, isolating opposing viewpoints and discouraging the exploration of nuance or common ground. The capitalist-driven models that shape social media algorithms tend toward prioritizing content which triggers a strong emotional response in users. Unfortunately, this kind of content is more likely to divide people instead of encouraging nuanced discussions which seek common ground. Extremism on social media has been shown to contribute to anti-democratic movements, as evident in the events of the January 6th insurrection at the United States Capitol (Jeppesen et al., 2022).

For a thick democracy to flourish, citizen participation must extend beyond national elections to encompass regular and sustained community engagement. Social media platforms offer spaces for debate, information dissemination, and advocacy, where visual content can play an important role. Images that evoke emotional responses can inspire citizens to seek justice, rally around causes, and highlight social issues that might otherwise be ignored. However, for these platforms to genuinely enhance a thick democracy, citizens must be able to engage with one another online in thoughtful, inclusive and nuanced dialogue. Visual media can contribute to meaningful discussion online when audiences are armed with the appropriate tools to navigate such material.

Unveiling Bias: Racism and Classism in Visual News

Analogue photography, by design, has historically been employed to propagate narratives infused with racial prejudice. The Kodak Shirley Card, which was used by photographers as early as the 1950s, provides an example of racial biases and race-based constructs of beauty embedded within the photographic process (del Barco, 2014). The card functioned as an industry standard, used to adjust exposure, and featured light-skinned women, not only making a statement about what was defined as beautiful but also technically setting the cameras to underexpose darker skin tones (Roth, 2009). It took until the 1990s for Kodak to finally include a variety of skin tones.

Returning to examples from COVID-19 coverage, discernible visual patterns emerged, revealing indications of the intersectionality between racism and classism. Examining illustrations from various international outlets, including The BBC (2020), CBC News (Chung, 2020), Hindustan Times (Mullick, 2020), and Time Magazine (Hincks, 2020), a recurring theme involved depictions of healthcare workers pointing temperature guns and disinfectant spray at the bodies of working-class individuals from racialized communities. Although pointing an infrared thermometer at a person’s head is less overtly violent than shooting disinfectant into someone’s face, in both cases, the decision to photograph this moment–and publish it–is in question. In these photographs, racialized, working-class communities are depicted as ‘the problem’ in the context of the pandemic, often targeted by aggressive measures enforced by authorities. Addressing this issue, Toby Miller and Pal Ahluwalia (2020) wrote, “The current pandemic brings into sharp relief the fault lines of inequality that divide the world both between and within sovereign states, compelling near-universal fear and suffering” (p. 571). Marginalized populations are at significant risk during a pandemic due to the intersecting nature of oppression (Milan et al., 2021). Rather than garnering attention and much-needed support, these photographs elicit blame and hostility.

The United Nations (2020) acknowledged concerns regarding the infodemic that plagued society in parallel with the pandemic, cautioning online users of malicious attempts to sell fake cures for the virus and to spread false information, preying on the public’s interest to seek guidance amid fear and panic. The responsibility that accompanies the role of news communication in the lives of people extends beyond the photographer. There is collective accountability that includes the actions of the publishers, producers and consumers of content. If we aspire to halt the perpetuation of misrepresentation as consumers of information, we as netizens must take on an active role in shaping the media landscape; this involves a deliberate and discerning choice to abstain from endorsing (liking and sharing) and disseminating content that perpetuates distortion.

The media platforms facilitating the spread of mis –and disinformation must also be held accountable. Facebook’s internal research discovered the significant negative impact Instagram has had on teen girls, particularly in relation to body image, with connections between app usage and higher rates of anxiety and depression (Wells et al., 2021). Furthermore, studies on Reddit indicate that the design of the system rewards users who post content which elicits strong emotional responses, regardless of whether those responses are positive or negative (Davis & Graham, 2021). As Bail (2021) found in multiple studies conducted on social media, these platforms tend to amplify extreme content, prioritizing posts that keep users engaged online for more extended periods. The capitalist goals driving the design of social media platforms mean that profits are put before well-being, and emotionally triggering content takes center stage.

While Meta has launched automated software meant to flag false information, these systems do not catch every instance and struggle, particularly with memes and other visually manipulated material that combine text and graphics (Garimella & Eckles, 2020). The World Health Organization launched a team of “Mythbusters” working across multiple social media platforms to counter fake news (United Nations, 2020). While this represents a significant step in combating the infodemic, Meeker (2014) reported that approximately 1.8 billion images were uploaded to the internet daily — a figure that has undoubtedly increased since then — rendering a manual review system inadequate for effectively filtering out false visual information. Given the magnitude of circulating visual material, addressing this issue must occur at an individual level through the citizens’ development of media, digital, and visual literacy practices, as well as collectively at community, policy, and business levels. A collective effort to address the ethical impact of visual representation can foster a more equitable and nuanced news media, supporting informed public discourse.

Visual Narratives of Death: Ethical Considerations

During the pandemic, many consumers of daily news understandably were fixated on the reported infection rates and escalating death tolls, which caused severe and widespread concern. News outlets were responsible for reporting on the gravity of the circumstances, inevitably obliged to address the delicate nature of human mortality. Grappling with the topic of death represented in photography is no easy task, and historically, this challenge has been fraught with ethical debate. Western media have demonstrated a tendency to disproportionately use non-white and marginalized bodies to illustrate death in graphic detail. Ghanaian photographer and activist Nana Kofi Acquah (2020) pointed this out during the pandemic, comparing the lack of published photographs displaying dead bodies during a peak death rate in Italy to the typical representation of explicit images of death and suffering in Western media coverage of crises on the African continent.

To explore this disparity, it is helpful to examine visual representations within one particular Western media publication to compare and contrast examples of the visual representation of death. Looking at the New York Times, an article published in March 2020 titled “Photos From a Century of Epidemics” (Cowell, 2020) includes twenty-five images covering content from as early as the 1918 influenza epidemic through to the modern-day coronavirus. The collection illustrates a mix of visual content, including individuals in various hospital settings, people receiving vaccinations, and many instances of mask-wearing. Notably, two images in the collection portray individuals marked for death: the final moments of David Kirby, a victim of the AIDs epidemic who died in 1990, and a photograph of James Dorbor, an eight-year-old boy who died of Ebola in Liberia in 2014.

Judith Butler, reflecting on the representation of death, wrote:

Can we read the workings of social power precisely in the delimitation of the field of such objects, objects marked for death? And is this part of the irreality, the melancholic aggression and the desire to vanquish, that characterizes the public response to the death of many of those considered “socially dead,” who die from AIDS? Gay people, prostitutes, drug users, among others? (1997, p. 27).

As noted by Kofi Acquah (2020), Butler, and Threadcraft, mentioned earlier in the chapter, there is evidence to indicate that marginalized members of society are disproportionately used to visually represent death within hegemonic frameworks of control. In Necropolitics, Achille Mbembe writes, “To exercise sovereignty is to exercise control over mortality and to define life as the deployment and manifestation of power” (2019, p. 557). Analyzing the imagery selected in the New York Times article reveals a telling pattern: the two images of soon-to-be-deceased individuals are racialized or otherwise marginalized. The treatment of these photos draws attention to the broader dynamic of power and representation.

While David Kirby was depicted in the now-iconic photograph surrounded and embraced by family members in an intimate and empathetic scene, James Dorbor is portrayed in an incredibly disturbing position. He is dangling from his left arm, which is held up by a hazmat-clad healthcare worker who marches forward against a backdrop of garbage and a dilapidated sheet metal wall. Dorbor’s body twists between the grip of the first healthcare worker and that of the second, another person entirely covered by protective gear who trails behind, arm outstretched to carry Dorbor’s right ankle. Dorbor wears no shoes, and his shirt has shifted upwards during the process to reveal his midsection, emphasizing his vulnerability. While his minders are covered head to toe in protective gear, Dorbor’s face, arms and middle are bare. The image raises critical ethical questions: Were these the last people to hold this boy before he died? Is this the kind of image that should be published and republished? Is this the kind of photograph that should have won “Photo of the Year” (Business Wire, 2015)? This comparison reveals stark inequalities in the representation of death, drawing attention to the ways in which power and marginalization shape visual narratives.

Examining additional examples from the pandemic, The New York Times (Gebrekidan et al., 2020) published a color photograph of a man lying dead on the street in Wuhan in the early days of the outbreak. Taken from a distance, part of the man’s face is visible in the image, and local viewers could have potentially identified the neighborhood based on the background elements included in the frame. Strikingly, two healthcare workers in biohazard suits had their backs turned to the man; no one in the photograph is tending to the victim. It appears very little care has been taken to anonymize the deceased. The photo appears to be the result of a quick snapshot of the situation. How would this presentation of the loss of life impact a family member or neighbor who came to learn about this man’s death by viewing this photo?

Contrasting this portrayal, The New York Times (Montgomery & Jones, 2020) published an article titled How Do You Maintain Dignity for the Dead in a Pandemic? and in the featured photo, Nick Farenga, a funeral director, cradles the body of a COVID-19 victim wrapped in a body bag while moving it from storage to a stretcher. The photo is presented in black and white rather than in color, a conscious choice, perhaps to emphasize the gravity of the situation and the seriousness of the content. Farenga, clad in transparent protective gear revealing a dress shirt and tie, is contextualized by a caption noting that the image was “altered to obscure a name to protect the privacy of the deceased” that would have otherwise been visible on the body tag (Montgomery & Jones, 2020, image caption). Farenga is surrounded by body bags in the small storage space; the shelves which line the left and right draw the viewer’s eye toward Farenga and the body he lies on a stretcher. You cannot see the face of the deceased, as it is concealed within the body bag, and the publication went to the additional extent of blurring the information on the body tag. This treatment is significantly different from the image taken in Wuhan described above. These instances from The New York Times underscore a hegemonic inclination to employ racialized bodies for the portrayal of distressing news, demonstrating a discernible discrepancy in the level of care exercised when the depicted victims are White. This analysis reveals some of the imbalances in values that influence visual reporting, emphasizing the need for ongoing critiques, which hold photographers, editors and publications, as well as consumers of this material, accountable for their contributions to visual culture.

While the examples in this section focus on the pandemic and one particular publication, there are examples that stretch before and beyond. The disparity in the visual representation of death requires critical reflection. Systemic biases should be addressed, and Western media publications must attend to the ethical concerns that arise in photojournalism; dignity, respect and privacy should be assumed rights for the many, not only for those in power. Hegemonic structures of power shape visual representations in media, which perpetuate issues of racism and inequality. As social media continues to play a significant role in contemporary life, photographs published online will continue to circulate and impact audience worldviews. Accountability must not rest only upon individuals; the social change required to address these issues must also be the responsibility of large media corporations, gatekeepers, and policymakers worldwide.

Fostering Visual Literacy Competence

The deliberate and continuous cultivation of a discerning gaze contributes to the development of visual literacy skills. Activists like Miqdaad Versi and Nana Kofi Accquah have used online public forums to hold accountable those who abuse the power of imagery, demanding social justice through collective witnessing. These contributions encourage critical dialogue in public spaces while supporting the ongoing development of visual literacy skills within audiences. Berger’s (1972) Ways of Seeing provided an example of a television program that encouraged conversations with the general public and aimed to decode visual stimuli collectively. Programs that provide an open space for visual rhetoric analysis in the same vein as Berger’s continuing to exist today, with The Photo Ethics Podcast (Dodd, 2023) and The Bigger Picture (Brown, 2023) as online examples. Inspired by the public programs hosted in educational spaces like Gulf Photo Plus (www.gulfphotoplus.com) in Dubai, UAE and the Bombay Institute for Critical Analysis and Research in India (www.bicar.org), Juniper Mind (Jones et al., 2020) initiated a series of visual literacy workshops to facilitate discourse on the topic, engaging myself, Jolaine Frizzell, and Nadine Khalil as workshop leaders for consecutive programs on coverage of COVID-19, of international protests, and the Beirut explosion, respectively (Jones et al., 2020). These conversations also led to our presentation at the 2022 UNESCO DCMET symposium[1]. These are only a few examples of programming committed to fostering meaningful dialogue and reflection on the transformative power of imagery.

The acquisition of visual literacy skills requires dedicated practice, a process facilitated by resources such as the UNESCO Media and Information Literacy (MIL) website (www.unesco.org/en/communication-information/media-information-literacy), which offers free online courses, age-appropriate curricula, and supplementary materials across various age groups (UNESCO, 2022). Additionally, The Critical Media Project (www.criticalmediaproject.org) provides educators and students aged 8-21 with a complimentary resource designed to foster critical thinking, empathy, and youth advocacy for societal change. Catering to adult learners, the Photography Ethics Centre (www.photoethics.org) produces a podcast, online training, lectures, and interactive workshops examining photography’s ethics and impact. These examples represent a subset of the diverse resources available to support visual literacy skill development and, more broadly, media literacy pedagogies.

Visual literacy education can be integrated into various facets of society, thereby supporting citizens as they seek information about their nation and their relationship with the world through critical analysis. Such education should begin in early childhood, with curricula designed for students as young as those in kindergarten, and should extend beyond the classroom into everyday environments, including the home. Educators and parents must collaboratively reinforce these lessons. Traditional news media can embody visual literacy practices through ethical journalistic practices, ensuring diverse representation at all levels of employment and actively debunking misinformation and disinformation as part of their reporting strategy. Governments can contribute to the ongoing struggle against fake news by enacting policies and legislation that hold businesses accountable for disseminating false or misleading information. International organizations can support the governmental policy process by providing research, developing global standards, and facilitating cross-border collaborations to combat mis – and disinformation.

To resist the influence of propaganda, it is essential to implement comprehensive visual literacy education that empowers citizens to critically analyze and interpret visual information. This process involves teaching individuals of all ages how to identify false information and encouraging a deeper understanding of the intent and context behind visual media. Visual literacy initiatives can include public awareness initiatives and educational programs for young learners and adults alike, which emphasize the importance of understanding visual narratives and the powers that shape them. These initiatives must be supported by the social media platforms themselves, who must execute their plans for combating the spread of mis-and disinformation. In addition, platforms must re-evaluate their algorithmic sorting systems to ensure that false information cannot go viral.

Several governments and advising organizations have already begun to address this issue through various education-focused initiatives. MediaSmarts (2024) in Canada has issued a Digital Media Literacy Framework for Canadian Schools, providing a comprehensive approach to digital media literacy lessons spanning Kindergarten to Grade 12. The United States Department of Education (2024) just released a National Educational Technology Plan which explores various strategies for promoting digital literacy throughout the education system. The European Commission (2020) published the Digital Education Action Plan for 2021 – 2027, which includes measures to enhance digital and media literacy among citizens across the European Union. The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Foundation has developed a regional initiative titled the ASEAN Digital Literacy Programme (2022), which aims to combat fake news and misinformation by enlisting community members and government officials as leaders of change. In Nigeria, The National Information Technology Development Agency (NITDA) has set specific targets which aim to achieve high rates of digital literacy by 2030 and include revisions to existing curricula, the establishment of digital literacy centres and collaborations with international organizations (Chukwudiebere, 2024). A thick democracy is upheld by an informed society; strong visual literacy and media literacy skills aid citizens as they navigate false information.

Conclusion

For media, digital, and visual literacies to exert meaningful influence, they must extend beyond theoretical frameworks and be grounded in practical applications that benefit society; without this, they are like a Pygmalion sculpture without a living, breathing form. In the post-digital age, a thriving thick democracy depends on the active role of digitally literate citizens, who can use digital platforms to learn, share and build community. They must simultaneously navigate mis –and disinformation and propaganda as it circulates online. As explored in this chapter, democratic participation is shaped, at least in part, by the visual content dominating our popular culture, news streams and social platforms. However, consumers of photojournalism must recognize that each image is a carefully constructed artifact, shaped by the photographer’s deliberate choices and influenced by their values and biases. Scholars and experts, as explored above, underscore the critical importance of visual literacy in decoding these cultural influences and in identifying the biases inherent in the photographic medium.

The interplay of race, class, gender and socio-economic status, which manifests in visual form, emphasizes the ethical complexities entwined with visual storytelling, necessitating an acute awareness of the implications of image-making. While diverse, ethical, and equitable representation in front of the camera is essential, it risks becoming mere virtue signaling if such diversity does not extend to those behind the camera and in the editing rooms. Analyzing photographs that depict death across various contexts—from public spaces to funeral homes—invites a critical examination of how dignity is either upheld or undermined and how political ideologies are either reinforced or contested in the visual representation of mortality. Critical media literacy praxis must include visual literacy as a vital skill for navigating visual mis – and disinformation and propaganda on social media. As the digital revolution democratizes image-making and broadens distribution channels, a critical opportunity arises to cultivate a visual culture that transcends oppressive tendencies. Part of the broader effort to understand the mechanisms of power must include an ongoing visual literacy praxis.

Appendix

“This illustration, created at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), reveals ultrastructural morphology exhibited by coronaviruses. Note the spikes that adorn the outer surface of the virus, which impart the look of a corona surrounding the virion, when viewed electron microscopically. A novel coronavirus, named Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), was identified as the cause of an outbreak of respiratory illness first detected in Wuhan, China in 2019. The illness caused by this virus has been named coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).” Credit: Alissa Eckert, MSMI, Dan Higgins, MAMS

Source: Center for Disease Control. (2020). Details—Public Health Image Library(PHIL). https://phil.cdc.gov/Details.aspx?pid=23312

References

ASEAN Foundation. (2022, February 11). ASEAN Digital Literacy Programme. ASEAN Foundation. https://www.aseanfoundation.org/asean_digital_literacy_programme

Bail, C. (2021). Breaking the social media prism: How to make our platforms less polarizing. Princeton University Press.

Balmer, C. (2020, March 19). Coronavirus death toll in Italy surpasses 3,400, overtaking China’s. Global News. https://globalnews.ca/news/6702620/coronavirus-italy-deaths-china/

Barthes, R. (1977). Image, music, text: Essays (S. Heath, Trans.; 13th ed.). Fontana.

BBC. (2020, July 6). Coronavirus: India overtakes Russia in Covid-19 cases. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-53303870

Benjamin, R. (2019). Race after technology: Abolitionist tools for the new Jim code. Polity.

Berger, J. (Director). (1972). Ways of Seeing [Broadcast]. BBC. https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p00hmb29

BICAR. (n.d.). Bombay Institute for Critical Analysis and Research (BICAR) [Educational Institution]. https://www.bicar.org/

Brown, V. (2023). The Bigger Picture [Broadcast]. https://www.pbs.org/show/bigger-picture/

Business Wire. (2015, March 18). Daniel Berehulak Wins Photo of the Year 2014 at Anadolu Agency’s 1st Istanbul Photo Awards. Business Wire. https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20150318005067/en/Daniel-Berehulak-Wins-Photo-of-the-Year-2014-at-Anadolu-Agencys-1st%C2%A0Istanbul-Photo-Awards

Butler, J. (1997). The psychic life of power: Theories in subjection. Stanford University Press.

Chukwudiebere, M. (2024, February 26). NITDA Targets 95% Digital Literacy In Nigeria By 2030. Voice of Nigeria. https://von.gov.ng/nitda-targets-95-digital-literacy-in-nigeria-by-2030/

Chun, W. H. K. (2018). Queerying Homophily. In C. Apprich, W. H. K. Chun, F. Cramer, & H. Steyerl, Pattern Discrimination (pp. 59–98). University of Minnesota Press.

Chung, E. (2020, April 18). Is spraying disinfectant in public spaces a good way to fight COVID-19? | CBC News. CBC. https://www.cbc.ca/news/health/disinfectant-sprays-1.5536516

Cowell, A. (2020, March 20). Photos From a Century of Epidemics. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/20/world/europe/coronavirus-aids-spanish-flu-ebola-epidemics.html

Davis, J. L., & Graham, T. (2021). Emotional consequences and attention rewards: The social effects of ratings on Reddit. Information, Communication & Society, 24(5), 649–666. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2021.1874476

del Barco, M. (2014, November 13). How Kodak’s Shirley Cards Set Photography’s Skin-Tone Standard. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2014/11/13/363517842/for-decades-kodak-s-shirley-cards-set-photography-s-skin-tone-standard

Dodd, S. (2023). The Photo Ethic Podcast [Broadcast]. https://www.photoethics.org/podcast

European Commission. (2020, September 30). Digital Education Action Plan (2021-2027). European Education Area: Quality Education and Training for All. https://education.ec.europa.eu/focus-topics/digital-education/action-plan

Flagg, J. M. (1917). I want you for U.S. Army: Nearest recruiting station (POS – US .F63, no. 9 (C size) [P&P] POS – US .F63, no. 9a another copy [P&P] POS – US .F63, no. 9b another copy) [Graphic]. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/pp.print. https://www.loc.gov/resource/ppmsca.55870/

Garimella, K., & Eckles, D. (2020). Images and Misinformation in Political Groups: Evidence from WhatsApp in India. Harvard Kennedy School Misinformation Review. https://doi.org/10.37016/mr-2020-030

Gaudette, T., Scrivens, R., Davies, G., & Frank, R. (2021). Upvoting extremism: Collective identity formation and the extreme right on Reddit. New Media & Society, 23(12), 3491–3508. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444820958123

Gasher, M., Skinner, D., & Coulter, N. (2020). Media & communication in Canada: Networks, culture, technology, audiences (Ninth edition). Oxford University Press.

Gebrekidan, S., Apuzzo, M., Qin, A., & Hernández, J. C. (2020, November 2). In Hunt for Virus Source, W.H.O. Let China Take Charge. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/11/02/world/who-china-coronavirus.html

Giaimo, C. (2020, April 1). The Spiky Blob Seen Around the World. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/01/health/coronavirus-illustration-cdc.html

Giroux, H. A., & Simon, R. I. (1994). Pedagogy and the Critical Practice of Photography. In Disturbing Pleasures: Learning Popular Culture (Kindle Edition). Taylor and Francis.

Goldberg, V. (1993). The power of photography: How photographs changed our lives (1. expanded and updated paperback ed). Abbeville.

Gulf Photo Plus. (n.d.). Gulf Photo Plus [Photography Centre]. https://gulfphotoplus.com/

Hincks, J. (2020, May 28). How COVID-19 is Spreading Undetected Through Yemen. Time. https://time.com/5843732/yemen-covid19-invisible-crisis/

hooks, bell. (2015). Black looks: Race and representation. Routledge.

Jeppesen, S., Hoechsmann, M., ulthiin, iowyth hezel, VanDyke, D., & McKee, M. (2022). Capitol Riots: Digital media, disinformation, and democracy under attack. Routledge.

Jones, K., McKee, M., Frizzell, J., & Nadine, K. (2020). Visual Literacy Workshops [Online Workshops]. Juniper Mind Programming. https://www.instagram.com/junipermind

Kellner, D., & Share, J. (2019). The critical media literacy guide: Engaging media and transforming education. Brill Sense.

Kiely, E., Robertson, L., Rieder, R., & Gore, D. (2020, October 3). Timeline of Trump’s COVID-19 Comments. FactCheck.Org. https://www.factcheck.org/2020/10/timeline-of-trumps-covid-19-comments/

Kofi Acquah, N. [@africashowboy]. (2020, March 19). Nana Kofi Acquah on Instagram: “Just before you start arriving in Africa with your cameras to document Covid-19… My condolences to all who’ve lost loved ones….” [Photograph]. Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/p/B95_3UyIiXM/

Kynge, J., Yu, S., & Hancock, T. (2020, February 6). Coronavirus: The cost of China’s public health cover-up. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/fa83463a-4737-11ea-aeb3-955839e06441

Löfflmann, G. (2013). Hollywood, the Pentagon, and the cinematic production of national security. Critical Studies on Security, 1(3), 280–294. https://doi.org/10.1080/21624887.2013.820015

Lyons, B. A., Montgomery, J. M., Guess, A. M., Nyhan, B., & Reifler, J. (2021). Overconfidence in news judgments is associated with false news susceptibility. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(23), e2019527118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2019527118

Mbembe, A. (2019). Necropolitics. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1215/9781478007227

MediaSmarts. (2024). USE, UNDERSTAND & ENGAGE: A Digital Media Literacy Framework for Canadian Schools – Overview. MediaSmarts Canada’s Centre for Digital Media Literacy. https://mediasmarts.ca/teacher-resources/digital-literacy-framework/digital-literacy-framework-overview

Meeker, M. (2014). 2014 Internet Trends (p. 164). Kleiner Perkins Caufield Byers. https://www.kleinerperkins.com/perspectives/2014-internet-trends/

Meyer, D. P. (Director). (2024, November 11). Host Jon Stewart sits down with journalist and retired Marine Thomas Brennan, founder of The War Horse. (Season 29, Episode 123), [TV Series episode]. In J. Stewart & J. Flanz (Executive Producers), The Daily Show. Comedy Central; Paramount+ Canada

Milan, S., Treré, E., & Masiero, S. (Eds.). (2021). COVID-19 from the margins: Pandemic invisibilities, policies and resistance in the datafied society. Institute of Network Cultures.

Miller, T., & Ahluwalia, P. (2020). The Covid conjuncture. Social Identities, 26(5), 571–573. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504630.2020.1824359

Monea, A. (2022). The digital closet: How the internet became straight. The MIT Press.

Montgomery, P., & Jones, M. (2020, May 14). How Do You Maintain Dignity for the Dead in a Pandemic? The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/14/magazine/funeral-home-covid.html

Mullick, J. (2020, July 17). 10 cities account for half of India’s active Covid-19 infections. Hindustan Times. https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/10-cities-account-for-half-of-india-s-active-infections/story-jA9UvWLUfC2hzBoZkytaaP.html

Photography Ethics Centre. (n.d.). Photography Ethics Centre. Photography Ethics Centre. Retrieved November 29, 2022, from https://www.photoethics.org

Roth, L. (2009). Looking at Shirley, the Ultimate Norm: Colour Balance, Image Technologies, and Cognitive Equity. Canadian Journal of Communication, 34(1). https://doi.org/10.22230/cjc.2009v34n1a2196

Sensoy, Ö., & DiAngelo, R. J. (2017). Is everyone really equal? An introduction to key concepts in social justice education (Second edition). Teachers College Press.

Simon, R. I. (2012). Disturbing Pleasures Learning Popular Culture (H. A. Giroux, Ed.). http://www.vlebooks.com/vleweb/product/openreader?id=none&isbn=9780203873250

Threadcraft, S. (2017). North American Necropolitics and Gender: On #BlackLivesMatter and Black Femicide. South Atlantic Quarterly, 116(3), 553–579. https://doi.org/10.1215/00382876-3961483

Treisman, R. (2021, April 21). Darnella Frazier, Teen Who Filmed Floyd’s Murder, Praised For Making Verdict Possible. NPR. https://www.npr.org/sections/trial-over-killing-of-george-floyd/2021/04/21/989480867/darnella-frazier-teen-who-filmed-floyds-murder-praised-for-making-verdict-possib

UNESCO. (2022). Media and Information Literacy. UNESCO. https://en.unesco.org/themes/media-and-information-literacy

UNESCO DCMET YouTube Playlists. (n.d.). UNESCO DCMET. Retrieved August 15, 2024, from https://www.unesco-dcmetyoutube.com

United Nations. (2020, March 31). UN tackles ‘infodemic’ of misinformation and cybercrime in COVID-19 crisis. United Nations; United Nations. https://www.un.org/en/un-coronavirus-communications-team/un-tackling-%E2%80%98infodemic%E2%80%99-misinformation-and-cybercrime-covid-19

United Nations Department of Global Communications. (2020, March 31). UN tackles ‘infodemic’ of misinformation and cybercrime in COVID-19 crisis. United Nations. https://www.unesco.org/en/covid-19/communication-and-information-response

U.S. Department of Education. (2024, January 22). U.S. Department of Education Releases 2024 National Educational Technology Plan | U.S. Department of Education. U.S. Department of Education. https://www.ed.gov/news/press-releases/us-department-education-releases-2024-national-educational-technology-plan

Versi, M. (2020, March 24). Editors of @TheEconomist should be ashamed at themselves for allowing the magazine to be a platform where #COVID19 is exploited for bigotry Whilst this specific tweet has now been quietly deleted there’s no acknowledgement of the error nor an apology Where’s the accountability? https://t.co/NK8q9aoHpY [Tweet]. Twitter. https://twitter.com/miqdaad/status/1242363218728833025

Wells, G., Horwitz, J., & Seetharaman, D. (2021, September 14). Facebook Knows Instagram Is Toxic for Teen Girls, Company Documents Show. Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/articles/facebook-knows-instagram-is-toxic-for-teen-girls-company-documents-show-11631620739

Zhang, M. (2020, May 2). Controversial Photo of “Crowds” on CA Beach Was Shot with a Telephoto Lens. PetaPixel. https://petapixel.com/2020/05/02/controversial-photo-of-crowds-on-ca-beach-was-shot-with-a-telephoto-lens/

Zenou, T. (2022, May 27). ‘Top Gun,’ brought to you by the U.S. military. Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2022/05/27/top-gun-maverick-us-military/

- A full recording of the session can be found on the UNESCO Chair DCMET website by navigating to the 2022 English sessions and selecting “Visual Literacy as social action: Photography praxis for social change.” Jones, Frizzell and McKee provide an overview of the program and content explored in the visual literacy workshops held in October of 2020 while Rohit Goel contributed a pedagogical perspective, reflecting on the role of image in contemporary society. ↵