12. Strengthening student teachers’ capabilities and creating transformative democratic spaces through practical-esthetical learning

Claudia Lenz & Merethe Skårås

Abstract

This chapter explores how a course design in pre-service teacher education, combining theory of historical thinking and aesthetic learning methods in the exploration of narratives and representations of colonialism, can strengthen student capabilities (Nussbaum, 2003, 2011) and create transformative democratic spaces in education. The study is placed within the ambiguity between normative and transformative notions related to democratic citizenship education within the Norwegian national curriculum (Udir, 2018). Focusing on compliance with democratic values on the one hand, and the need to challenge democratic “tokenism” on the other, there is a space for critical and transformative pedagogies. We explore this space by highlighting the importance of modeling learning processes fostering individual growth, authentic experience of participation and critical historical awareness. The data material consists of student surveys, classroom observations and experiences from peer teaching and reflections throughout the intervention. Our findings show that students developed a deeper, critical understanding of both the historical subject and are equipped with perspectives that challenge legacies of colonial and racist imagination. Further, the students could develop an extended understanding of what it requires to be a teacher by experiencing alternative to what Giroux calls “oppressive pedagogy”, focused on measurable learning outcomes and competitiveness. In that way, both their professional knowledge and skills (“being able to do”) and their professional ethos (“being able to be”) have been transformed towards a more inclusive and critical stance. Thus, we argue that the interplay of critical theoretical and esthetic learning methodologies can create non-normative and transformative spaces of democratic learning by developing students’ capabilities in at least three interrelated dimensions: What are students able to do and to be as learners; what are they able to do and to be as future professionals; and what are they able to do and to be as critical citizens.

Keywords: esthetical learning, history didactics, capability, non-normative democratic citizenship education, democratic learning spaces, critical historical awareness, tokenism, inclusivity.

Résumé

Ce chapitre explore comment une conception de cours dans la formation initiale des enseignant·e·s, combinant la théorie de la pensée historique et les méthodes d’apprentissage esthétique dans l’exploration des récits et des représentations du colonialisme, peut renforcer les capacités des étudiant·e·s (Nussbaum, 2003, 2011) et créer des espaces démocratiques transformateurs dans l’éducation. L’étude se situe dans l’ambiguïté entre les notions normatives et transformatrices liées à l’éducation à la citoyenneté démocratique dans le cadre du programme national norvégien (Udir, 2018). En mettant l’accent sur le respect des valeurs démocratiques d’une part, et sur la nécessité de remettre en question le « symbolisme » démocratique d’autre part, il existe un espace pour les pédagogies critiques et transformatrices. Nous explorons cet espace en soulignant l’importance de modéliser des processus d’apprentissage favorisant la croissance individuelle, l’expérience authentique de la participation et la conscience historique critique. Les données proviennent d’enquêtes auprès des élèves, d’observations en classe, d’expériences d’enseignement par les pairs et de réflexions tout au long de l’intervention. Nos résultats montrent que les étudiant·e·s ont développé une compréhension plus profonde et critique du sujet historique et sont équipé·e·s de perspectives qui remettent en question les héritages de l’imaginaire colonial et raciste. En outre, les étudiant·e·s ont pu développer une compréhension élargie de ce qu’exige le métier d’enseignant·e, en expérimentant une alternative à ce que Giroux appelle la « pédagogie oppressive », axée sur les résultats d’apprentissage mesurables et la compétitivité. De cette manière, leurs connaissances et compétences professionnelles (« être capable de faire ») et leur éthique professionnelle (« être capable d’être ») ont été transformées en une position plus inclusive et critique. Ainsi, nous soutenons que l’interaction entre la théorie critique et les méthodologies d’apprentissage esthétique peut créer des espaces non normatifs et transformateurs d’apprentissage démocratique en développant les capacités des étudiant·e·s dans au moins trois dimensions interdépendantes : ce que les personnes étudiantes sont capables de faire et d’être en tant qu’apprenantes; ce qu’elles sont capables de faire et d’être en tant que futures professionnelles; et ce qu’elles sont capables de faire et d’être en tant que citoyennes et citoyens critiques.

Mots-clés : apprentissage esthétique, didactique de l’histoire, capacité, éducation à la citoyenneté démocratique non normative, espaces d’apprentissage démocratiques, conscience historique critique, symbolisme, inclusivité.

Resumen

Este capítulo explora cómo un diseño de curso en la formación inicial de docentes, que combina la teoría del pensamiento histórico y métodos de aprendizaje estético en la exploración de narrativas y representaciones del colonialismo, puede fortalecer las capacidades de los estudiantes (Nussbaum, 2003, 2011) y crear espacios democráticos transformadores en la educación. El estudio se sitúa en la ambigüedad entre las nociones normativas y transformadoras relacionadas con la educación para la ciudadanía democrática dentro del currículo nacional noruego (Udir, 2018). Al centrarse, por un lado, en el cumplimiento de los valores democráticos y, por otro, en la necesidad de desafiar el “tokenismo” democrático, existe un espacio para pedagogías críticas y transformadoras. Exploramos este espacio destacando la importancia de modelar procesos de aprendizaje que fomenten el crecimiento individual, la experiencia auténtica de participación y la conciencia histórica crítica. El material de datos consiste en encuestas a estudiantes, observaciones en el aula y experiencias de enseñanza entre compañeros y reflexiones a lo largo de la intervención. Nuestros hallazgos muestran que los estudiantes desarrollaron una comprensión más profunda y crítica tanto del tema histórico como de perspectivas que desafían los legados de la imaginación colonial y racista. Además, los estudiantes pudieron desarrollar una comprensión ampliada de lo que se requiere para ser docente al experimentar alternativas a lo que Giroux llama la “pedagogía opresiva”, centrada en resultados de aprendizaje medibles y competitividad. De esta manera, tanto su conocimiento y habilidades profesionales (“ser capaces de hacer”) como su ética profesional (“ser capaces de ser”) se han transformado hacia una postura más inclusiva y crítica. Así, argumentamos que la interacción entre metodologías de aprendizaje crítico y estético puede crear espacios no normativos y transformadores de aprendizaje democrático al desarrollar las capacidades de los estudiantes en al menos tres dimensiones interrelacionadas: ¿Qué son capaces de hacer y de ser como aprendices? ¿Qué son capaces de hacer y de ser como futuros profesionales? ¿Y qué son capaces de hacer y de ser como ciudadanos críticos?

Palabras clave: aprendizaje estético, didáctica de la historia, capacidad, educación para la ciudadanía democrática no normativa, espacios de aprendizaje democrático, conciencia histórica crítica, tokenismo, inclusividad.

Introduction

In a time of interconnected global crisis, related to climate change, social injustice and military conflicts, democracy has come under pressure. The world democracy index (EIU, 2024) shows an increase in countries under authoritarian rule, as well as weakened and compromised democracies. Populists and antidemocratic movements profit from the shrinking legitimacy of politicians, and the political system seems to be enjoying declining support among citizens. In this situation, education for democratic citizenship (EDC) cannot only promote a self-contented and triumphalist notion of liberal democracy. It needs to respond to the challenges and grievances leading people to turn their backs on democracy, and to contribute to a renewal and re-imagination of lived and sustainable democracy.

This chapter focuses on Norway, which is defined as a full democracy and ranked number 1 on The Economist Intelligence Unit’s Democracy Index (2023). We question how our future teachers can be prepared to empower students to become active participants in democratic processes oriented towards the realization of human dignity, human capabilities and social justice. In this, we choose an entry point towards education for democratic citizenship, which does not assume the state of things in Western, liberal democracies to be perfect and the role of education to socialize students into functioning as citizens within this given system. As the human dignity of many groups, minorities in western societies, and large parts of the populations of the Global South are violated by all kinds of economic and political injustice, the vision of democracy needs to be assumed as unfulfilled, also in Norway.

Central to our approach, thus, is the idea of fulfillment of the full human potential (expressed in Martha Nussbaum’s capability approach) as a vision for our students’ personal and professional development, as well as their capacity to become active and critical citizens. Teacher education, thus, does not only need to support students to acquire the necessary subject-related knowledge and teaching thinking skills, but also support them in becoming democratic role models and facilitators of transformative democratic learning environments. The focus on the learning process in itself and the space it provides for students’ personal development and growth lies at the heart of critical pedagogy. This process-oriented approach contrasts with what Freire (1970) calls the “banking ideal of teaching” – the idea of filling students with knowledge necessary to function in a given economic and political system. In order to not only be subjected to but also become agents of change against injustices and inequalities in society, all students need to get the space and tools necessary for developing alternative outlooks on what society and democracy can be. Carr (see Chapter 1 of this volume) argues that the Pygmalion discourse on democracy risks perpetuating a false consciousness, suggesting that democratic systems function seamlessly and that this normative narrative not only obscures the realities of systemic inequities but may also hinder meaningful efforts towards substantive social change. In our case, we explore how and in what ways the combination of historical-theoretical and practical-esthetical learning methods used in teacher education genuinely can support practices that empower students to critically interrogate and transform these structures.

On the one hand, ideas of experience based on democratic learning (Dewey) and the democratization of teacher-student relations have influenced the field of education for democratic citizenship during the last few decades. This led to a shift in focus from the transmission of “civic knowledge” to the development of democratic competence and a democratic mindset within democratic learning environments and through democratic experience. This is reflected in the notion of learning “about, through and for” democracy (Council of Europe, 2017).

On the other hand, global neoliberal trends, related to individualization, competitiveness and accountability, have dominated educational systems in the same period. Giroux (1981, 2022) points to the pacifying and, thus, oppressive nature of efficiency and outcome-driven education. At the least, we can see a deeply embedded systemic ambiguity between democratization and neoliberal marketization in Western educational systems.

This ambiguity is also reflected in the recently renewed Norwegian school curriculum (LK20), which has a strong and affirmative focus on democracy and citizenship. One innovation in this curriculum is the inclusion of democracy and citizenship as a cross-curricular theme. However, when studying the core curriculum (Norwegian Ministry of Education, 2020), which spells out the value base for primary and secondary education in Norway, one finds a tension between a normative and transformative outlook on democracy. The chapter on democracy and citizenship starts with a clear normative message:

The teaching and training shall promote belief in democratic values and in democracy as a form of government. It shall give the pupils an understanding of the basic rules of democracy and the importance of protecting them. (Section 1.1, online)

This paragraph appears to be normative and static: “Promoting values” and “giving pupils an understanding of basic rules” do not seem to leave much room for critical evaluation and reflection regarding how these values and rules are defined, might be interpreted and negotiated. However, in the chapter dedicated to the cross-cutting curricular theme democracy and citizenship, a more dynamic approach expresses how pupils, through work on the topic, “shall learn why democracy cannot be taken for granted and understand that it must be developed and maintained” (Section 2.5.2, online).

In the curriculum chapter dedicated to critical thinking, the need to give space for new insights and ideas, related to tolerance of ambiguity, is underlined:

If new insight is to emerge, established ideas must be scrutinized and criticized by using theories, methods, arguments, experiences and evidence.(…) Critical reflection requires knowledge, but there is also room for uncertainty and unpredictability. The teaching and training must therefore seek a balance between respect for established knowledge and the explorative and creative thinking required to develop new knowledge. (Section 1.3, online)

The national curriculum, thus, is informed by an ambiguity between a normative focus on the preservation and reproduction of the existing democratic system, its institutions and rules, on the one hand, and a critical outlook, focusing on the need for democratic renewal and transformation on the other. For teacher education, this opens a space to make these underlying ambiguities explicit, and to explore in which ways teaching designs can challenge and transform institutionalized forms of pacifying and thereby oppressive (Giroux 1981, 2022) educational practices.

In this chapter, we present an educational intervention aiming to broaden this critical and transformative democratic educational space. We explore how the combination of theory of historical thinking and the use of esthetical learning methods, applied to narratives and counter-narratives emerging from colonialism, might enable the students’ “human capabilities” (Nussbaum, 1997, 2003) to flourish in a history/social science course in teacher education. The students’ engagement with theoretical concepts in the encounter with colonial representations and narratives, as well as post-colonial and decolonial critique and counter-narratives, emanates from reflections on historical agency and capability (Nussbaum, 1997, 2003). Thus, we argue that our teaching design has the potential to foster the interplay of cognitive, emotional, and intersubjective dimensions of learning, as well as professional meta-cognition. This is important and central because it has the potential to contribute to deconstructing oppressive narratives and practices in education.

Human capabilities for transformative democratic engagement

One of the core theoretical assumptions in our teaching design lies in the usefulness of the capability approach, as developed by Sen (1985a, 1985b) and Nussbaum (1997, 2003, 2011) in determining how a teaching intervention contributes to the students’ professional and personal development. For Nussbaum (2003, p. 39), a focus on human capabilities is intrinsically linked to “a conception of the dignity of the human being, and of a life that is worthy of that dignity – a life that has available in it ‘truly human functioning’’. The capability approach asks what people are able to do and able to be within a wide range of areas crucial for the full realization of human dignity and quality of human life. Capabilities are conceptualized as fundamental entitlements, and thereby focusing both on the basic conditions a state needs to provide for its citizens in terms of social justice, and on a person’s individual possibility to realize his/her full potential in pursuing a good life with the objective of pursuing critical forms of social justice.

Nussbaum’s list of ten fundamental capabilities (1997, 2003) covers the full scope of human existence (life, bodily integrity and health). Nussbaum’s capabilities provide an outlook towards democracy based on human dignity as well as social and environmental justice.

The scope of what Nussbaum envisions as part and parcel of the fully developed human potential highlights the need to support future teachers in realizing their own capabilities as individuals, professionals, and citizens as a precondition for realizing democratic transformation in and through education. For our study, thus, four of the capabilities on Nussbaum’s list (2003, p. 41) are of particular interest: a) senses, imagination and thought, b) emotions, c) practical reason, and d) affiliation. Senses, Imagination, and Thought are significant for our study, as they explicitly include creative and artistic expressions as human ways of making sense of and engaging with the world. This, again, composes a foundation for critical forms of agency. Emotions, and the ability to have emotional attachments to humans and non-human species, but also the non-living environment, form a precondition for the realization of meaningful human existence and coexistence. This capability is, therefore, crucial for the personal and professional development of future teachers, and, thus, relevant for our study. Practical Reason is relevant for our study, as it focuses on the moral dimension of human existence, the freedom of conscience and ethical responsibility by being able to form a conception of the good and to engage in critical reflection about the planning of one’s life. The last capability of specific relevance to our study is Affiliation. This capability has two dimensions. One focuses on the ability to recognize and show concern for other human beings, to engage in various forms of interaction and imagine the situation of another. The other dimension focuses on the ability to develop a basis of self-respect and the ability to be treated as a dignified being whose worth is equal to that of others. This capability stresses intersubjective recognition, mutual respect and the acknowledgement of equal value, which is critical for the professional development of future teachers in working with their students and in their communities of praxis.

Summing up, the four capabilities have been selected as they point to dimensions of human existence, action and interaction, being crucial for teachers’ personal and professional development. We use Nussbaum’s lens to analyze if, and to what extent, these capabilities are fostered through a combination of esthetical learning and historical-critical thinking in our teaching design in view of democratic transformation in and through education.

Taking teacher students on a journey of non-hegemonial democratic learning

The empirical basis of this chapter is an intervention-based educational design study, characterized by collaboration between stakeholders aiming to simultaneously develop both new theoretical insights and practical solutions to serious teaching and learning challenges (McCanny & Reeves, 2020, p. 83). Our study is based on the cooperation between two teacher-educators, involving students as participants in the study. Within a framework of a Norwegian program for the prevention of prejudice, racism and other forms of group-based hostility (Lenz & Nustad, 2016), the challenges we wished to find solutions for were related to our students’ capabilities as individuals, teachers and citizens participating in a democratic society. Based on the experiences of marginalization of groups and individuals in learning situations, we wanted to include more students as active learners in the classroom who could also contribute with their stories and perspectives. Through this approach, a normative or triumphalist notion of liberal democracy is challenged, and space is given to both insight in the deeply rooted injustices of the status quo, but also for the extended imaginary of alternative democratic visions and practices. The two authors’ objective was to introduce new teaching methods, redistribute power (and speech time) and agency in the classroom, pointing beyond the classroom, to both transformative professional and democratic practices.

We lean on Hansen’s and Jensvoll’s (2020) definition of esthetical learning processes, where “the student learns through participation and creation to rework, reflect, and communicate about themselves and the world”. Our use of esthetical learning methodologies, thus, is informed by the holistic, humanist idea of education aiming to form and transform the entire human being and the social and political contexts it is a part of. This idea, rooted back to the German “Bildung” tradition, is also a center piece of critical pedagogy. Democratic education, going beyond instrumental knowledge and skills needed to “function” as a citizen within the status quo of society, here entails the imaginative dimension of being able to take part in democratic processes. The aesthetic dimension here points beyond the mere maintenance of a systemic status quo, but also towards the imaginary of a “better world” in terms of social justice, equal rights and the full realization of equal human values. This vision of citizenship requires a critical and creative mindset, which can be fostered through esthetic learning processes. Referring to Dewey (1934/1980), Kokkos (2010) points to the links between aesthetic learning and critical thinking when stating that “the aesthetic experience is wider and deeper than the usual experiences that we acquire from reality, and it constitutes an important ‘challenge for thought’.” (Kokkos, 2010, p. 159).

Kuttner (2015) establishes the connection between esthetical expressions and active democratic participation through the concept of “cultural citizenship”, that is, the full participation in socio-cultural and cultural processes, which are essentially intertwined with democratic deliberation and decision making. In the context of teacher education, this deeply transformative dimension is also relevant for the nexus between student teachers’ personal and professional development. In the context of our study, the use of aesthetic learning methodology has a deep connection to Nussbaum’s notion of “being able to” and “being able to be” as central to both being/becoming a professional (teacher) and a critical democratic citizen.

Our underlying hypothesis was that the use of visual physical learning artifacts and practical aesthetic teaching methods, together with a toolbox of core concepts in historical thinking, would enable students to use a wider variety of meaning-making when engaging in the learning process, thus establishing the basis of critical awareness and transformative agency.

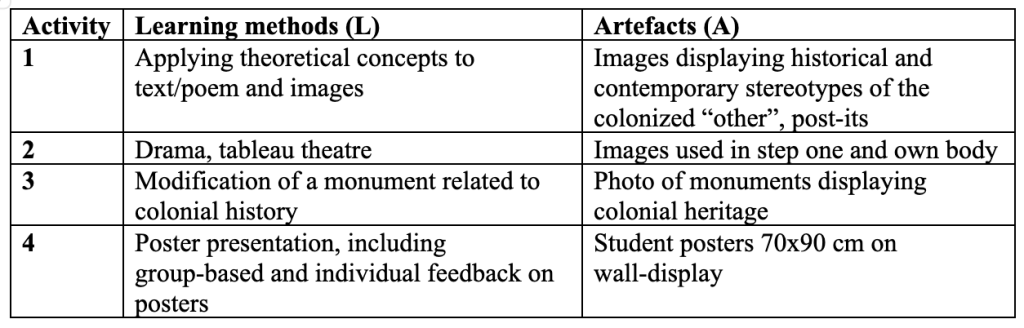

Table 12.1 provides a visual overview of the four steps of the teaching design and the reflective processes included in this study[1].

Sixteen student teachers, following a five-year master’s program to become teachers in the subjects of social science and religion, took part in the teaching intervention. Many of these students had a first or second-generation non-Western migrant background.

The four steps of the teaching design include reflection cycles undertaken to develop human capabilities through the learning processes. An underlying assumption was that applying different teaching methodologies, including practical-esthetical methods, would allow students to engage in the teaching in a broader variety of ways. In the following, we will focus on three out of the four steps of the intervention (first, third and fourth step), as these most clearly exemplify the development of the students’ capabilities and a transformative democratic space through the interplay between esthetic learning processes and critical engagement on the topic of colonial narratives and counter narratives.

The evolving transformative democratic space

How did the different elements of our teaching intervention influence students’ capabilities related to their personal and professional development, as well as their capacity to become active participants in non-hegemonic democratic processes? We will follow three of the steps to see how democratic spaces beyond the self-content, Pygmalion discourse emerged.

Applying theoretical concepts to text/poem and images

The introductory lectures on the course were used to familiarize the students with the key theoretical concepts needed to critically unpack historical narratives and representations, as well as the esthetical learning methodology. The main theoretical approaches to historical thinking (Seixas, 2017) were exemplified by the ways in which historical narratives and memory culture about marginalized and colonial history are constructed.

As humans and as citizens, we are always embedded in temporalized contexts. Traditions and heritage, as well as the narrative about past injustices and struggles against these injustices, have an enormous impact on how we understand ourselves as individuals and part of different collectives and communities. Moreover, this, again, opens – or limits – our potential outlook towards the future, which developments we can imagine achieving, or prevent from happening. In our study, we focused on the ways in which the colonial past has been represented and commemorated in Western/Norwegian historical culture, which traces the colonialist imaginary of The white man’s Burden (Kipling, 1899) and the inferiority of the colonized has left in contemporary cultural expressions, and how the idea of “Norwegian exceptionalism” has contributed to a self-imagination of being distanced and innocent related to colonial injustice (Jore, 2019).

Historical consciousness and agency are closely interrelated, and the ability to critically reflect on the nexus between history, culture, memorialization and power relations is a precondition for the realization of critical democratic agency. In our study, the core concepts of historical thinking (Seixas, 2017) formed the backbone of the course content, aiming to provide students with tools to unpack and critically analyze historical narratives.

The “Big Six” historical thinking concepts (Seixas & Morten, 2013; Seixas, 2017) encompass central aspects of historical meaning-making, starting from the question of historical significance (why should any historical event be relevant for the posteriority to deal with?), via key principles of historical scientific method (evidence and interpretation, continuity and change, causality), to the questions of historical perspective taking and empathy and, finally, ethical considerations in dealing with history. These principles provide a toolbox to reflect on the basic ways in which historical accounts and narratives are established, including the power relations they reflect and reproduce.

Our students were engaged in group-work, applying Seixas’ principles to the construction and reproduction of the notion of white superiority. The students had to link Rudyard Kipling’s poem, White Man’s Burden (1899), and some visual images reflecting Kipling’s key message of the white man’s plight to “carry” the inferior black race towards civilization. This included historical photographs showing European colonizers and colonized black African people, and historical colonial caricatures, as well as motives related to modern slavery and racist imagery in Western popular culture.

Other images that accompanied this lecture were cartoon images of “Urban Legend” (Yohannes, 2017) (See figure 12.1) and Tintin in the Kongo (Hergé, 2021), and photos of stereotyping commodities in our everyday lives, such as the racist illustration of the Norwegian spice brand “Black-boy” (See figure 12.2).

![Figure 12.1: Urban Legend comic [Illustration]](https://scienceetbiencommun.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/101/2025/05/Screenshot-2025-06-30-152611-214x300.png)

![Figure 12.2: Black Boy spice [Illustration]](https://scienceetbiencommun.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/101/2025/05/Screenshot-2025-06-30-152641-189x300.png)

All these examples highlighted that historical and contemporary oppression and violence are legitimated by images of the other as inferior and dangerous – and that the struggles against this symbolic dehumanization are part of emancipatory struggles for equal rights and equal dignity. In this way, students could develop a deeper understanding of the interrelatedness between memory, history, politics and the struggles for identity and power were established, refuting ideas of Norwegian exceptionalism and national being related to colonial history.

By applying Seixas’ dimensions of historical reasoning, the students gained insights into the legacies of colonial oppression, represented in everyday life and popular culture in contemporary societies.

Historical Significance

This dimension, asking why a historical reference to colonialism still matters in our time, seemed to be quite intuitive for the students. Among the contemporary examples that were highlighted was the Tintin cartoon showing the prevalence of racist tropes and the need to come to terms with these stereotypes in our own societies. The visual presence of open expressions and consequences of historical colonial racism seemed to create an awareness about the legacies and destructive impact of contemporary racist expressions, even if they are supposedly humorous.

Continuity and Change

Using historical and contemporary sources dealing with racialized injustice, exploitation and violence, some groups posed the question of whether and to what degree colonial racism has changed and what indicates such change. These reflections brought up the issue of the long-lasting consequences of colonial injustice, which can even be traced in contemporary Norwegian society. In this, the notion of “Norwegian exceptionalism” – the idea of Norwegians being disconnected from and innocent concerning colonial history – was challenged. This critical historical awareness is a crucial precondition for a transformative future orientation.

The Ethical Dimension

Almost all groups addressed the immorality of colonial racism and the importance of awareness in the present. Related to this, the question of the limits between ethical and unethical representations of historical and contemporary racism was raised. Can the dignity of the victims be violated by representing injustice? This historical concept contributes to strengthening the awareness that history writing and historical culture are interwoven with historical injustices, which can be legitimized and reproduced by historical narratives. However, historical representations and narratives are also part and parcel of anticolonial struggles for freedom and justice.

The choice and operationalization of these concepts underscores that the students developed significant insight related to the power dynamics and moral implications of historical accounts and history writing about colonialism. As the exploration of the legacies of colonial violence also created links to the Norwegian context, ideas of Norwegian exceptionalism (Gullestad, 2002; Jore, 2019) and, thereby, hegemonic notions of Norwegian identity and the nexus between national identity and citizenship were challenged.

This deeper nexus between intellectual learning and being emotionally invested in questions of identity, power and oppression was facilitated by the combination of theoretical and esthetic stimuli. The learning activity seemed to create a productive interplay of cognitive and social learning, in which the artifacts played a central mediating role. The vast majority of students evaluated the session positively, almost all of them pinpointing the importance of the practical activity for processing the theoretical concept introduced in the lectures. One of the students commented:

Theory is useless (strong word, perhaps) unless it can be applied in practice and understood through examples, events and history. I think these teaching methods did just that, they contextualized and supplemented the theory we had learned, which gave me an increased understanding.

Applying theoretical concepts to visual material and poetry proved fruitful as a form of processing and providing a deeper understanding of historical narratives related to colonial injustice. Applying Nussbaum’s work, this points to an interplay of capability #4 (senses, imagination and thought) and #6 (practical reasoning) as well as the productivity of integrating practical-aesthetic and cognitive dimensions in the development of ethical-historical judgment. Further, both the interaction between the students and the historical empathy they displayed throughout the group work can be linked to the capability of affiliation, a sense of attachment and responsibility for the concrete and more abstract others.

Modification of a monument

In this session, students were given the task of modifying a pre-selected monument related to hegemonic or marginalized historical narratives by using creative means (drama or drawing). The lesson started with an introductory lecture on how monuments and counter monuments are part of the negotiations and struggles about historical narratives in a society. This affirmed the previous session’s learning point that memory and historical culture can become a part of hegemony and oppressive power, as well as a means of anti-hegemonial struggles. Using recent debates about monuments that are linked to problematic legacies, questions on whether monuments should be removed, or kept and/or modified in order to raise historical awareness were brought up. Subsequently, the students were organized into groups and asked to: a) argue for the continuing existence or determination of a given monument; and b) suggest a modification or transformation of that monument with the use of theoretically informed arguments, using Seixas. The monuments, picturing Cecil Rhodes, Mahatma Gandhi, Ludwig Holberg and Fritjof Nansen, have all been subject to contested debates regarding oppressive colonial and nationalist narratives.

After having explored the meaning and debates related to the respective monuments, none of the groups suggested the removal of any of these, even though some of them quite clearly were part of legacies of colonial and racist ideology. However, the students concluded it would be better to add elements informing and critically commenting on these legacies and they came up with creative suggestions as to how to do so. In our view, choosing such an “educative” approach, the students displayed a combined professional and civic awareness. The data show how the activity facilitated theoretical understanding among the students, similar to activity 1.

While a few students reported this as a boring activity and difficult, partly due to a lack of background knowledge, the majority had positive experiences, giving critical space for discussion, collaboration, and creativity. The inclusion of a diversity of abilities relates to Nussbaum’s (2003) capability affiliation, making all students able to be treated as dignified human-beings, whose worth is equal to that of others (p. 42).

Poster presentation

One course requirement was to visit a place where history is communicated, then create a poster and make a presentation for the other students on the course. Most of the students choose places related to “difficult histories”, such as monuments or institutions where historical atrocities, racist violence and terror are commemorated. Two of the posters were explicitly related to colonial history. Interestingly, many of the students visited places which were related to their biography, often a site in the geographical location of their origin. In this way, the assignment touched upon the pedagogy of discomfort (Boler, 1999; Zembylas, 2015), enabling students to engage in problematic historical aspects related to their personal, local and national identity. This stands in contrast to the employment of historical culture for the construction of hegemonic identity construction. The assignment, thus, gave room for the students to construct their own narratives based on primary source evidence, escaping exceptionalist and triumphalist frameworks. Engaging in uncomfortable aspects of collective history and places of belonging creates a critical resilience against hegemonic ideological uses of history and can, thus, be regarded as a significant aspect of critical democratic citizenship. Therefore, the historical narratives presented through the posters by students challenged the collective memories and monumental history that dominate course literature and the public debate in such a way that students were able to identify oppressive structures and practices. The classroom became a transformative democratic space open to new perspectives.

Student conversations during the poster presentations showed further how students learned to engage in each other’s personal background and history (capability, affiliation). Many students shared stories about their parents and grandparents, making other students curious and asking questions related to identity and belonging. During a conversation between a student presenter and a student listener, the latter is rather amazed when he comments on a fascinating story of immigration to Norway, “You have never told me about your father before”, while the student replies, “you never asked”. These interactions between and among lecturers and students in the poster exhibition setting enabled students’ capabilities to be recognized. The conversations enabled a space where students used senses, imagination and thought (capability no. 4), and thereby opened transformative democratic spaces. Many students refer to these conversations in the exhibition as educational, both by listening to fellow students’ presentations and through their own repetitive presentations during the exhibit.

Conclusion: Transcending the exceptionalist democratic discourse in teacher education

Our study illustrates how the interplay of historical theoretical concepts and esthetical learning methods, applied in a course design focusing on historical representations and narratives of colonialism, created transformative democratic spaces, recognizing students’ unique and various capabilities in three interrelated ways:

The students’ personal development

Through our observations of the students’ actions and interaction as well as the data collected from the students throughout and after the intervention, we can see development and growth in many of the students. We could observe critical intellectual capacities and conscientization (Freire, 1970) related to ways in which history and historical culture can contribute to reproducing – or disrupting – legacies of colonial and racist injustice. But this intellectual growth cannot be separated from their growth in terms of self-expression and interpersonal encounters, in which the students acknowledged and respected each other as bearers of experience and views, which could enrich each other. In a regular lecture situation, interpersonal encounters and sharing of views and experiences are most often reserved for the few that dare to raise their hands and participate by their own will and confidence. Our design, through the use of artefacts like images and wall displays, gave space and confidence to minoritized students and their narratives. This brought out experiences and perspectives that challenged the status quo. Both students and lecturers were exposed to new ways of thinking and being, establishing a more informed foundation for real democratic dialogue. In line with the principles of critical and anti-oppressive pedagogy, the support of the personal growth of the learner is a precondition for his/her empowerment and freedom to act as professionals and citizens. In this way, educational design challenged self-content and exceptionalist democratic discourse and instead created a learning space where everyone has the opportunity to participate by transforming the classroom into a space where everyone participates and engages in interpersonal encounters based on knowledge and experiences.

The students’ professional development

As outlined at the beginning of this chapter, teacher training in Norway operates within a systemic ambivalence between an outlook towards education, which focuses on the realization of the full human potential (“Bildung”), as well as the constant critical renewal of democracy, on the one hand, and a neoliberal, efficiency and accountability orientated outlook on the other. The latter is related to instrumentalist approaches and what Giroux calls “oppressive pedagogies”, dominated by the focus on measurable results and competitiveness. Our teaching intervention was designed to create an experience-based space for our students to familiarize themselves with alternative, non-oppressive pedagogies that empower all students regardless of intellectual, academic capacities, background or experiences. Our study reveals that the variety of teaching and learning approaches applied enabled students to engage according to their needs and preferences. This realization emerged at two levels, one related to personal development, the other related to each student’s professional development in a community of practice.

On a realistic note, it is important to acknowledge that our teaching intervention was placed within the context of an educational system strongly focusing on measurable outcomes, and which exercises discipline through grades. Our students, too, deliver an assignment that is assessed according to academic standards with an option to fail. This limits the space for non-hegemonic democratic practice, but it is this maneuver within opportunities that signifies transformative endeavors.

The student’s capacity to act as a critical citizen

The intellectual and esthetic exploration of narratives and representations related to colonialism created an awareness of the deeply imbedded – and embodied – legacies of dehumanization of the “colored other”, white supremacy and Norwegian exceptionalism, which play a central role in legitimizing and normalizing injustice. This kind of awareness, and the discomfort related to it, are a precondition for the capacity and willingness to actively take part in the ongoing debates about racism, the struggles against discrimination and for social justice (locally and globally). Our study does not include any data on whether our students, in fact, plan to, or are actively taking part in, these struggles. However, understood through the lens of Nussbaum’s capabilities: as democratic educators, our task is to widen our students’ scope of what they are “able to do” and “able to be” and to open non-hegemonial democratic spaces, which point beyond our own teaching.

References

Boler, M. (1999) A pedagogy of discomfort: witnessing and the politics of anger and fear, in M. Boler (ed.), Feeling Power, Taylor and Francis, 175‐202.

Council of Europe (2017) Reference Framework Competences for Democratic Culture. Strasbourg: Council of Europe.

Dewey, J. (1934/1980). Art as experience. The Penguin Group.

Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) (2024). Democracy Index 2023. Age of Conflict. https://www.protothema.gr/files/2024-02-15/Democracy-Index-2023-Final-report.pdf

Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU). (2025). Democracy Index 2024. Economist Intelligence Unit. https://services.eiu.com/campaigns/democracy-index-2024/

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Penguin Books.

Giroux, Henry (1981). Ideology, Culture and the Process of Schooling. Temple University Press.

Giroux, Henry (2022). Pedagogy of Resistance: Against Manufactured Ignorance. Bloomsbury Academic.

Gullestad, M. (2002). Invisible Fences: Egalitarianism, Nationalism and Racism. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 8(1), 45–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9655.00098

Hergé (2021). Tintin in the Kongo. Cobolt Forlag.

Jore, M. K. (2019). Eurocentrism in Teaching about World War One: A Norwegian Case. Nordidactica. Journal of Humanities and Social Science Education, 9(2). https://journals.lub.lu.se/nordidactica/article/view/19963/18009

Kemmis, S., McTaggart, R. & Nixon, R. (2014). The Action Research Planner. Doing Critical Participatory Action Research. Springer.

Kipling, R. (1899). The White Man’s Burden: The United States & The Philippine Islands, 1899. McClure’s Magazine, 12.

Kokkos, A. (2010). Transformative Learning Through Aesthetic Experience: Towards a Comprehensive Method. Journal of Transformative Education, 8(3), 155-177

Kuttner, P. J. (2015). Educating for cultural citizenship: Reframing the goals of arts education. Curriculum Inquiry, 45(1), 69-92. https://doi.org/10.1080/03626784.2014.980940

Lenz, C. & Nustad, P. (2016). Teoretisk og faglig forankring av Dembra. I. C. Lenz, P., Nustad & B. Geissert (Eds.), Dembra. Faglige perspektiver på demokrati og forebygging av gruppefientlighet i skolen. Senter for studier av Holocaust og livssynsminoriteter (HL-senteret). pp. 48–65.

McKenney, S., & Reeves, T. C. (2020). Educational design research: Portraying, conducting, and enhancing productive scholarship. Medical Education, 55(1), 82–92. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14280

Norwegian Ministry of Education. (2020). Core Curriculum – Values and Principles for Primary and Secondary Education. https://www.udir.no/lk20/overordnet-del/?lang=eng

Nussbaum, M. (1997). Capabilities and Human Rights. Fordham Law Review, 66, (273-300).

Nussbaum, M. (2003). Capabilities as fundamental entitlement: Sen and social justice. Feminist economics, 9(2-3), 33-59.

Nussbaum, M. (2011). Creating Capabilities. Harvard University Press.

Seixas, P., & Morton, T. (2013). The big six: Historical thinking concepts. Nelson Education.

Seixas, P. (2017). A Model of Historical Thinking. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 49(6), 593-605, https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2015.1101363

Sen, A. (1985a). Commodities and Capabilities. North-Holland.

Sen, A. (1985b). Rights and Capabilities in Morality and Objectivity: A Tribute to J.L. Mackie, (pp. 130-48) Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Yohannes, J. (2017). The Urban Legend. Sesong 2. Gyldendahl.

Zembylas, M. (2015). ‘Pedagogy of discomfort’ and its ethical implications: the tensions of ethical violence in social justice education. Ethics and Education, 10(2), 163–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/17449642.2015.1039274

- The course comprised lectures outside of this study before and in between some of the steps indicated in the table. ↵