11. Official document utopias: Constructing the brave new digitalized higher education

Marko Teräs, Hanna Teräs & Juha Suoranta

Abstract

In this chapter, we explore how international and national actors, such as the OECD and the European Union, national education agencies, and technology companies, create visions of the future of higher education through reports and vision papers. We argue that these documents can be seen as utopian literature, as they not only describe or predict the future but also produce and legitimize it, often using and reinforcing the legitimacy of neoliberal rhetoric. We call these documents “official document utopias” (ODUs), which in our analysis includes the following documents: OECD Skills Outlook 2019: Thriving in a Digital World, 2030 Digital Compass: The European Way for the Digital Decade, Microsoft’s The Class of 2030 and Life-ready Learning: The Technology Imperative, and a Finnish national initiative, Digivisio 2030. These policies are often overlooked and remain beyond democratic decision-making and opinion-shaping formation. Few people understand how these policies control, constrain and cultivate the direction of development behind parliamentary democratic decision procedures. Therefore, it is essential to conduct research highlighting the significance of such policy and vision documents in societal and political development. This chapter demonstrates that these documents are utopian in several ways. Firstly, they acknowledge and focus on certain current problems and crises that require solutions. Secondly, they frequently propose technology and digitalization as solutions to these problems. Thirdly, they implicitly and explicitly describe a better future. Fourthly, they create a sense of hope, and fifthly, they promote uniformity of thought. As such, the often technophilic, market-based future these documents promote and construct shifts focus from other important societal aspects for democracy, such as critical thinking, equality, and justice, in addition to important environmental questions that cannot be solved solely with new technologies. In light of a sustainable and democratic future, ODUs could also be seen as dystopian.

Keywords: digitalization, education, Finland, Europe, OECD, utopia, educational policies, vision papers, dystopia.

Résumé

Dans ce chapitre, nous explorons la manière dont les acteurs internationaux et nationaux, tels que l’OCDE et l’Union européenne, les agences nationales de l’éducation et les entreprises technologiques, créent des visions de l’avenir de l’enseignement supérieur par le biais de rapports et de documents d’orientation. Nous soutenons que ces documents peuvent être considérés comme de la littérature utopique, car ils ne se contentent pas de décrire ou de prédire l’avenir, mais le produisent et le légitiment, en utilisant et en renforçant souvent la légitimité de la rhétorique néolibérale. Nous appelons ces documents des « utopies de documents officiels » (UDO) qui, dans notre analyse, comprennent les documents suivants : OECD Skills Outlook 2019: Thriving in a Digital World, 2030 Digital Compass: The European Way for the Digital Decade, The Class of 2030 and Life-ready Learning: The Technology Imperative de Microsoft et Digivisio 2030, une initiative nationale finlandaise. Ces politiques sont souvent négligées et échappent à la prise de décision démocratique et à la formation de l’opinion. Peu de gens comprennent comment ces politiques contrôlent, contraignent et cultivent l’orientation du développement derrière les procédures de décision démocratiques parlementaires. Il est donc essentiel de mener des recherches soulignant l’importance de ces documents de politique et de vision dans le développement sociétal et politique. Ce chapitre démontre que ces documents sont utopiques à plusieurs égards. Tout d’abord, ils reconnaissent et mettent l’accent sur certains problèmes et crises actuels qui nécessitent des solutions. Deuxièmement, ils proposent souvent la technologie et la numérisation comme solutions à ces problèmes. Troisièmement, ils décrivent implicitement et explicitement un avenir meilleur. Quatrièmement, ils créent un sentiment d’espoir et, cinquièmement, ils favorisent l’uniformité de la pensée. Ainsi, l’avenir souvent technophile et basé sur le marché que ces documents promeuvent et construisent, détourne l’attention d’autres aspects sociétaux importants pour la démocratie, tels que la pensée critique, l’égalité et la justice, ainsi que d’importantes questions environnementales qui ne peuvent être résolues uniquement par les nouvelles technologies. À la lumière d’un avenir durable et démocratique, les UDO pourraient également être considérées comme dystopiques.

Mots-clés : numérisation, éducation, Finlande, Europe, OCDE, utopie, politiques éducatives, documents d’orientation, dystopie.

Resumen

En este capítulo, exploramos cómo actores internacionales y nacionales, como la OCDE y la Unión Europea, las agencias nacionales de educación y las empresas tecnológicas, crean visiones del futuro de la educación superior a través de informes y documentos de visión. Argumentamos que estos documentos pueden considerarse literatura utópica, ya que no solo describen o predicen el futuro, sino que también lo producen y legitiman, a menudo utilizando y reforzando la legitimidad de la retórica neoliberal. Llamamos a estos documentos “utopías documentales oficiales” (UDO), que en nuestro análisis incluye los siguientes documentos: OECD Skills Outlook 2019: Thriving in a Digital World, 2030 Digital Compass: The European Way for the Digital Decade, The Class of 2030 and Life-ready Learning: The Technology Imperative de Microsoft, y una iniciativa nacional finlandesa, Digivisio 2030. Estas políticas suelen pasar desapercibidas y quedan fuera de la toma democrática de decisiones y la formación de opiniones. Pocas personas entienden cómo estas políticas controlan, limitan y cultivan la dirección del desarrollo detrás de los procedimientos de decisión democrática parlamentaria. Por lo tanto, es esencial realizar investigaciones que resalten la importancia de tales documentos de política y visión en el desarrollo social y político. Este capítulo demuestra que estos documentos son utópicos de varias maneras. En primer lugar, reconocen y se centran en ciertos problemas y crisis actuales que requieren soluciones. En segundo lugar, frecuentemente proponen la tecnología y la digitalización como soluciones a estos problemas. En tercer lugar, describen implícita y explícitamente un futuro mejor. En cuarto lugar, crean un sentido de esperanza, y en quinto lugar, promueven la uniformidad del pensamiento. Como tal, el futuro a menudo tecnofílico y basado en el mercado que estos documentos promueven y construyen desvía el enfoque de otros aspectos importantes de la sociedad para la democracia, como el pensamiento crítico, la igualdad y la justicia, además de cuestiones ambientales importantes que no pueden resolverse únicamente con nuevas tecnologías. A la luz de un futuro sostenible y democrático, las UDO también podrían considerarse distópicas.

Palabras clave: digitalización, educación, Finlandia, Europa, OCDE, utopía, políticas educativas, documentos de visión, distopía.

If the modern Utopia is indeed to be a world of responsible citizens, it must have devised some scheme by which every person in the world can be promptly and certainly recognised, and by which anyone missing can be traced and found.

Wells (2009, p. 183)

Introduction

In this chapter, we explore how international and national organizations such as the OECD, UNESCO, the European Union, national education agencies, and technology companies such as Google and Microsoft envision the future of digitalization in higher education through vision documents, reports, and policy papers. We refer to these documents as “official document utopias” (ODUs) and examine how they function as imageries of the social world. Often, these documents contain policy recommendations and frameworks with fundamental ideas about desirable development, the state’s appropriate role, and effective governance principles in various fields, such as education and social work. Countries often try to adopt these international organizations’ (IOs) policy frameworks in their pursuit of socio-economic and educational advancement and recognition on the global stage. This occurs even if it is sometimes questionable whether these frameworks can be adapted to local contexts (Elfert & Ydesen, 2023), which are still as if caught in the gravitational pull of global cultural forces (Carney et al., 2012). The global circulation of such policies functions as a network of influences that facilitates the flow, adaptation, and dissemination of ideas across different countries (Carney et al., 2012). Policy templates might offer valuable guidance to countries, but their use also raises important questions about the balance between global norms and national and local contexts.

We argue that the dominant future vision of digitalization is driven by ‘neoliberal’ language and worldview (Teräs et al., 2020). There are many versions and uses of the term ‘neoliberalism’ (Freeden, 2015; Hall, 2011). When using the term, we follow Holborow’s (2016) notion of “neoliberal ideology as a world view which rests on the belief that market exchange is the guide for all human action and that social organization should be directed towards allowing the ‘free’ market to thrive.” (Holborow, 2016, p. 43; Holborow, 2015). With ‘neoliberal subjectivities’ we mean the education or the ‘subjectification’ (Stewart & Roy, 2014) of self-governing, “free, possessive individuals” (Hall, 2011, p. 706) with personal advancement (Freeden, 2015) and “self as enterprise” or an “entrepreneur” (McNay, 2009; Holborow, 2015, Chapter 5).

In the following subsections, we will first briefly trace the history of ‘utopia’ to create a background for our analysis of ODUs. Then we examine a selection of reports, discussion papers, vision documents, and policy papers at the international, regional, and national levels, including the OECD, UNESCO, the EU, and the edtech business sector. We will present their common themes and how they construct the future of the digitalization of higher education. Next, we look at Digivisio 2030 as an example of digitalization of higher education in Finland, and how its documentation participates in the process of domestication, that is, how nation-states adopt global trends and policy suggestions of international organizations and discourses (Alasuutari, 2009, 2016; Alasuutari & Qadir, 2019; Rautalin, 2012). Finland is a case in point when it comes to digitalization. At least for the past 20 years, it has been considered among the frontline countries in digitalization, with a highly developed education system, well-established digital infrastructure, high internet penetration, tech-savvy population, and state-wide digital policies (Castells & Himanen, 2002; Rinne, 2006). Lastly, we will end the chapter with a discussion on the possible implications of ODUs and their version of the future for democracy.

Utopia re-emerged

In analyzing the official documentation of higher education digitalization, we have utilized our reading and analysis of the utopian literature (Berneri, 2019; Bloch, 1995; Eskelinen, 2020; Levitas, 2013). Utopian writing highlights several distinct features that illustrate humanity’s aspiration toward a better future.

The term ‘utopia’ was first introduced by Thomas More in his book Utopia in 1516. The word ‘utopia’ derives from the Latin “a-topos,” meaning “a place that does not exist,” and from the Greek “eu-topos,” meaning “a happy place”. In summary, it is a desirable societal order and state of things (Kumar, 2003).

Throughout history, many works are considered to be utopian, including Francis Bacon’s New Atlantis (1626), Campanella’s The City of the Sun (1602), and De Foigny’s A New Discovery of Terra Incognita Australis (1676) and even Plato’s Republic (Berneri, 2019; Levitas, 2010). The 19th century was marked by the rise of industrial society and socialism, and its utopian literature includes Bellamy’s Looking Backward (1888) and Morris’ News from Nowhere (1890). Utopian socialism was also a popular vein of thought during this era, with authors such as Charles Fourier, Henri de Saint-Simon, Robert Owen, and Étienne Cabet espousing their views of perfect societal order (see also Bauman, 2003). Several sources argue that the turn to the 20th century saw the decline in utopias and being replaced by dystopias and anti-utopias (Marks et al., 2022). Authors such as Aldous Huxley in a Brave New World (1932) and George Orwell in 1984 (1949) are the most famous examples of the dystopian trend.

At the turn of the 20th century, the concept of utopia received a negative connotation due to its use in totalizing socialist future engineering (Levitas, 2010; Popper, 2013). There is also a relationship between utopia and dystopia, which often goes unnoticed: they are not opposite. While utopia as a concept has usually meant some kind of a desired future, dystopia has represented an undesired future or a utopia that has been ill-planned and serves only some people in society (Gordin et al., 2010). Understanding dystopia this way is related to egalitarianism and hope for a communal and egalitarian future, typically advocated by leftist intellectuals (Freire, 2014; Fromm, 1968; Rancière, 1991). Dystopian popular culture stories usually present some external entities, such as the state, large corporations, or technology that has taken power over the individual. Interestingly, it currently seems that emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI), which in popular culture have often appeared as causes for dystopia, are now seen as part of utopian visions and their utopian or dystopian nature does not appear as clear-cut as it does in popular culture. For example, in the case of AI, some see potential in it to support people in understanding how democracy and politics function and how to be more involved (Adam & Hocquard, 2023), while others see it as a threat to democracy with its efficient capabilities to produce misinformation (Kreps & Kriner, 2023).

Currently utopia seems to have re-emerged in different forms, for example, as ODUs. Unlike prime examples of utopian literature, ODUs do not come across as over-the-top or fictional. They are often developed by various actors, such as IOs and governmental institutions that possess authority and legitimize their future visions with co-creation processes and engaging various stakeholders. Still, we argue, these documents bear several shared elements with utopian literature.

Analyzing official document utopias (ODUs)

In this section, we identify shared elements in official documents, such as vision papers and reports addressing the potential of the digitalization of education and digital futures. Our analysis draws from Fairclough’s critical discourse analysis (2013) and interpretative meaning-making as described in hermeneutics (Gadamer, 2004; Langdridge, 2007; Ricœur, 1984). Based on our theoretical analysis of the concept of utopia (Berneri, 2019; Bloch, 1995; Eskelinen, 2020; Levitas, 2013), we argue that these documents are part of and form a dominant future utopian discourse. As, for instance, Fairclough (2013) noted, discourses suggest how the future could or should be, but they also renegotiate the past. They invent “possible worlds” and legitimize a particular world and ideology (Fairclough, 2013). According to Meretoja (2018), “cultural webs of narratives only exist through individual interpretations, and individual subjects are constituted in relation to cultural narrative webs” (p. 74).

At the beginning of the analysis process, we perceived ODUs as mere IO vision papers, but a closer reading soon led us to ask critical questions about the way they construct their future visions. For instance, they seemed to simultaneously predict and describe a predetermined future yet justify the sense of urgency with uncertainty of the future. Moreover, the future described appeared to reinstate and reproduce the neoliberal present, rather than envision a different future. Such questions made us draw the connection between the concept of utopia and imagining or speculating about the future. We used theoretical works about utopias (e.g., Berneri, 2019; Bloch, 1995; Eskelinen, 2020; Levitas, 2010) as an analysis framework for the ODUs. In practice, we organized our observations from utopian literature and corresponding observations from ODUs in tables, making connections and identifying similarities between them.

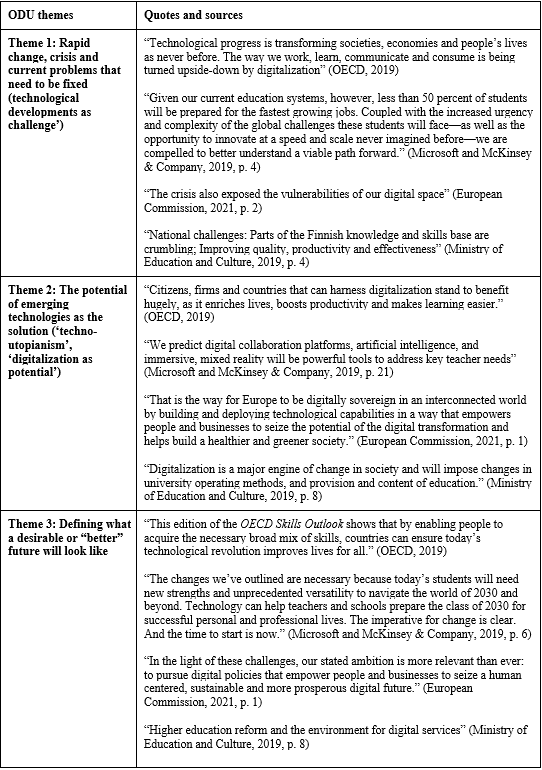

The analysis revealed five themes that construct ODUs. Firstly, there is a problem or crisis in the present which needs fixing. Secondly, technology and digitalization are seen as the solution to these problems. Thirdly, they describe a better future, with both implicit and explicit claims. Fourthly, they create a sense of hope, which encourages people to get involved in creating a better world. Finally, they promote uniformity of thought.

We have summarized these five themes in Table 11.1. It provides a concise summary, and direct quotations of the themes observed at intergovernmental, international, EU-regional, and national levels as well as the edtech business sector.

The above examples illustrate striking similarities between the logical flow of the documents analyzed: they all appear to follow the five steps of utopian discourse. This further solidifies the uniformity of thought they promote, creating a narrative that seems commonsensical and absent of alternative interpretations. It is important to note that these documents do more than present a utopian digital future, they influence the course of action on national and local levels. In the following section, we illustrate how this is taking place in the Finnish context.

‘Digivisio 2030’: The digitalization of higher education utopia materialized

In this section, we examine the Finnish national initiative Digivisio 2030 as an example of the domestication of official document utopias. Digivisio 2030 is a Finnish national-level initiative through which the Finnish Ministry of Education and Culture advances the digitalization of higher education in all higher education institutions in Finland. Although Finnish higher education institutions have historically had considerable autonomy, Digivisio 2030 shows how the government holds the political power to make structural educational changes in Finland.

The initiative springs from the Finnish Ministry of Education and Culture Proposal for Finland: Finland 100+ (Ministry of Education and Culture, 2019), published in 2017. The “Proposal” describes a vision and a roadmap for Finnish higher education and research in 2030. It aims to ensure that the Finnish Higher Education system will become effective and internationally competitive by 2030 (Ministry of Education and Culture, n.d.). Within the lines of ODU logic, the “Proposal” describes present problems and challenges that need to be dealt with before this better future can become reality. National challenges such as “parts of the Finnish knowledge and skills base are crumbling” and “quality, productivity and effectiveness” need to be tackled. In addition to national challenges, global changes and megatrends, such as the transformation of work, digitalization and global competition for skills, threaten Finland’s success. In addition to these challenges is that “[g]lobally Finnish higher education institutions are not yet as attractive and competitive as they could be” (Ministry of Education and Culture, 2019).

The background document to the Vision for higher education and research in 2030 (Ministry of Education and Culture, 2017) raises the following question: “How Finland, which is strong in technological preconditions, can maximize its benefits of digitalization?” (p. 8). Solutions are that Finland can achieve this by raising competence, continuous renewal, innovation, and being at the forefront of the implementation of new technologies. These will then “renew the Finnish success story which is based on education (“sivistys”[1]) and competence (“osaaminen”).” (p. 3)

The “Proposal” outlined and initiated five development programs. Development program 2, “Higher education reform and the environment for digital services”, describes digitalization as “a major engine of change in society [which] will impose changes in university operating methods, and provision and content of education” (Ministry of Education and Culture, 2019). The program has two main goals: 1) “Building a higher education environment for digital services” and 2) “Making education more digital, increasing modularity and reinventing teaching”. For example, in the Microsoft (2018) Transforming education document, pedagogy is described as something that needs to be transformed to match the potential and progress of digitalization: “Following the advances in digitalization and stronger international connections, more attention must be paid to pedagogic development” (Ministry of Education and Culture, 2019, p. 10).

This vision describes education as a “service environment” which “will improve accessibility and flexibility of education, the opportunities for continuous learning and global cooperation” (Ministry of Education and Culture, 2019). This service environment and flexibility mean providing more modularity, the possibility of studying digitally and attracting international students. In summary, the digitalization of Finnish higher education is seen as the vessel which will propel Finland to the 2030s and to global education markets. As the “proposal” describes, the aim of these reforms is to build “a higher education environment for digital services” (Ministry of Education and Culture, 2019). The Digivisio 2030 is the initiative to achieve that.

The general aim of Digivisio 2030 was originally described to make “Finland as a model country for flexible learning, and a global pioneer in higher education” (Digivisio 2030, 2021a) but has recently been described as” to create an internationally esteemed learning ecosystem that widely benefits society as a whole” (Digivisio 2030, n.d.). In the beginning the initiative was coordinated by Unifi (Universities Finland) and Arene (The Rectors’ Conference of Finnish Universities of Applied Sciences) with Aalto University and Metropolia University of Applied Sciences as the project leaders. Now, the initiative has its own program office, which is responsible for its practical implementation. As Digivisio 2030 is still a work in progress, it is difficult to predict the actual outcomes or impact of the initiative. Nevertheless, as a development initiative, it exemplifies how the utopian discourse present in ODUs turns into real-world changes.

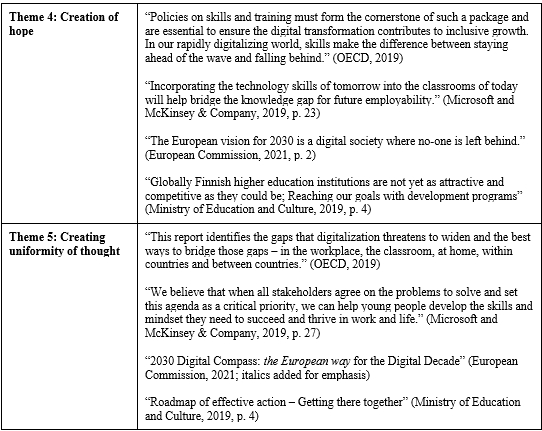

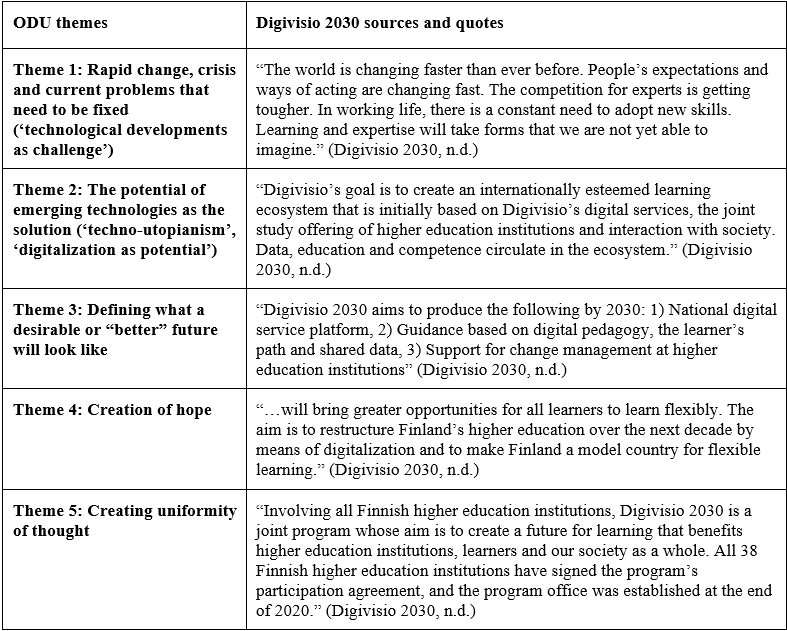

The communication of Digivisio 2030 and its supporting documents closely align with the ODUs’ logic, with a picture of rapid and inevitable change and crisis that must be addressed, introducing digitalization as a solution. Digivisio sets forth the ideals and objectives of the future by following a technology-centered roadmap. The initiative offers hope by contrasting the present crisis with its future vision. Furthermore, the proposed technological advancements are presented as the only logical measures to address the challenges described without being questioned or problematized and without any alternative options discussed. Additionally, all Finnish HEIs are involved in the initiative, creating a uniformity of thought. Table 11.2 provides examples of how ODU elements are present in the Digivisio 2030 communication.

Digivisio 2030 initial documents communicated four main “promises” which were to tackle current challenges at the individual, organizational and national level: 1) MyData for learners, 2) Learner’s benefit at the center of development, 3) Universities are open communities led with information and 4) Data for use by individuals and society.

The initiative is described as producing by 2030 a “national digital service platform” for higher education institutions to enhance service compatibility and learner integration; “digital pedagogy guidance” for promoting digital pedagogy to support students’ well-being and academic success with AI-driven tools; and “change management support” for assisting higher education institutions in adopting digital solutions, fostering knowledge-based management, and ensuring data accessibility for all (https://digivisio2030.fi/en/basic-information-on-the-digivisio-2030-programme).

From official document utopias to higher education institution reforms

The analysis of several official documents from international and national policy actors shows that they all share utopian characteristics. However, instead of envisioning alternative future trajectories, they seem to reinforce, reproduce, and accelerate the current business logic-driven educational policymaking. In this sense, ODUs are not open utopias, meaning, thought experiments critical of the present and visioning alternative and more democratic ways of future living (Lakkala, 2020, p. 23). While current utopias appear to promote individual freedom, they also often depict a future centered around technology and the subjectification of entrepreneurial-spirited neoliberal subjectivities who are able to function in the ‘free market’ (Holborow, 2015).

Furthermore, utopian discourse in ODUs makes the reality they communicate appear plain natural (Ydesen, 2019, pp. 295–6). We claim, however, that it is still utopian. Utopias can be considered unreachable, like mirages that keep drifting further despite all the seemingly made progress. This thought is not far-fetched when thinking of the endless discourse around the future potential of technologies that never seems to be fully achieved. As such, these documents rely on the nature of the very same thing they claim to predict or estimate: the uncertainty of the future and the “we cannot know for sure.” Naturally, this also makes it difficult to criticize such documents. Similarly, it makes the critique of technology difficult, as “the next version could always be better” – even if we still clearly do not have flying cars, most of us need to work eight hours a day, and emerging technologies will always need more natural resources. This is the power of the story of modern progress and the potential and promise of technology (Virilio & Richard, 2012).

Early critics of utopian thinking have argued that utopias, while appearing to be progressive, often create new inequalities by placing specific individuals and groups in positions of power and relegating others to servitude. A utopia might be a utopia for the privileged in society but simultaneously become a dystopia for the marginalized (Gordin et al., 2010). Examples of such accounts are illustrated in Margaret Atwood’s novel The Handmaid’s Tale (1985) which deals with women’s status in the patriarchal, religious totalitarianism of Gilead or real-world totalitarian systems such as Nazi Germany and the Stalinist USSR (Claeys, 2017).

International organizations such as the OECD, the EU, and others play a significant role in acting as overseers who navigate the complex interplay of power and knowledge, shaping the destinies of nation-states in subtle yet profound ways. Through data collection and policy reports, they forge the narratives that guide member states in their economic, social, and political pursuits. This is the artistry of governance, where knowledge becomes power. These organizations prescribe norms and benchmarks across various policy domains, ostensibly fostering cooperation and convergence (Krejsler, 2019).

ODUs can be seen as techno-utopias in that the role technology plays in them is central. They present an idealized individual who leverages technology in their pursuit of personal advancement in life, while simultaneously, technology is used by authorities to surveil and direct individuals. It is therefore worth noting, as Komljenovic et al. (2023) have observed, that investors in education technology have significant power over the future developments in education, and their imaginations of future states steer the behaviors of various actors – “imaginations upon which actors base their behaviour ‘as if’ these expectations actually did describe future states” (Komljenovic et al., 2023, p. 6). These imaginations have the power to persuade actors, such as policymakers, to make decisions within the lines of these narratives. For example, the EU has strategic initiatives to strengthen its role as an actor in the digital market (European Commission, 2015).

Conclusion

This chapter has examined how vision documents and discussion papers by international and national organizations such as the OECD, UNESCO, the EU and Finnish Ministry of Education, in alignment with international technology businesses, uphold and build a certain kind of digital future discourse. We argue that such vision documents and discussion papers are contemporary utopian works and have defined them as “official document utopias” (ODUs). We have identified five utopian themes in ODUs: 1) they describe a rapid change, crisis and current problems that need to be fixed (‘technological developments as challenge’), 2) they see emerging technologies as the solution to these problems (‘techno-utopianism’; ‘digitalization as potential’), 3) they define what a desirable or “better” future will look like, 4) they create hope that these challenges can be tackled and overcome and 5) they create uniformity of thought by engaging various stakeholders to imagine the future, but within the neoliberal worldview. As such, ODUs can be seen as pseudo-utopias because they reproduce and even reinforce the characteristics of the neoliberal worldview, rather than offering open alternatives.

Using the Finnish national initiative ‘Digivisio 2030’ as an example, the chapter illustrates how these global digital utopian visions have materialized as a national development program. The aim of the initiative is to unite all Finnish higher education institutions under the same platform in the pursuit of creating a higher education digital utopia. We also suggest that the initiative is an example of the domestication of global neoliberal trends described in ODUs. The concept of domestication refers to the process by which nation-states align global trends and policy recommendations in collaboration with IOs to achieve global policy objectives (such as the partnership between the Finnish Agency for Education and the OECD). However, domestication does not imply that IOs directly impact national policies.

Official document utopias (ODUs) influence the educational policies of nation-states. These documents represent the ideal educational system from the perspective of global educational actors, reflecting their aspirations, values and visions of a prosperous society. However, whether these goals and ideals align with those of education practitioners and students is unclear. Therefore, investigating the impact of ODUs on real-world educational practices would be an important area for research in social sciences. Examining the tangible effects of ODUs on curriculum design, pedagogical methods, and educational outcomes can provide valuable insights into how policy ideals translate and flow into actual pedagogical realities.

Such research would also be important for studying the state of democracy in education and as such, society at large, but also upholding democratic processes and making them visible where they are breaking. Gert Biesta (2010) argued that the question of “what is good education” has been replaced by the question of how to effectively manage, measure education and reform it based on the aims of neoliberalism and managerialism (see also Poutanen et al., 2022). Such reforms and policies may appear pragmatic and value-free, but they reform HE with the focus of entrepreneurialism and human subjects functioning well in the “disrupting” free markets. In this, critical thinking, social justice and building a more sustainable future in alternative ways get less attention. This is also the frame within which the brave new digital future of higher education appears to be emerging.

References

Adam, M., & Hocquard, C. (2023). Artificial intelligence, democracy and elections. European Parliamentary Research Service. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document/EPRS_BRI%282023%29751478

Alasuutari, P. (2009). The Domestication of Worldwide Policy Models. Ethnologia Europaea, 39(1). https://doi.org/10.16995/ee.1046

Alasuutari, P. (2016). The Synchronization of National Policies: Ethnography of the Global Tribe of Moderns (1 edition). Routledge.

Alasuutari, P., & Qadir, A. (2019). Epistemic governance: Social change in the modern world. Palgrave Macmillan.

Atwood, M. (1985). The Handmaid’s Tale. McClelland & Stewart.

Bacon, F. (1626). New Atlantis. Sylva Sylvarum.

Bauman, Z. (2003). Utopia with no Topos. History of the Human Sciences, 16(1), 11–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/0952695103016001003

Bellamy, E. (1888). Looking Backward: 2000-1887. Ticknor & Co.

Berneri, M. L. (2019). Journey Through Utopia: A Critical Examination of Imagined Worlds in Western Literature (Original work published 1950). PM Press.

Biesta, G. (2010). Good Education in an Age of Measurement: Ethics, Politics, Democracy. Paradigm Publishers.

Bloch, E. (1995). The Principle of Hope. Vol. 1 (N. Plaice, Ed.; 1. MIT paperback ed, Vol. 1). MIT Press.

Campanella, T. (1602). The City of Sun.

Carney, S., Rappleye, J., & Silova, I. (2012). Between Faith and Science: World Culture Theory and Comparative Education. Comparative Education Review, 56(3), 366–393. https://doi.org/10.1086/665708

Castells, M., & Himanen, P. (2002). The Information Society and the Welfare State: The Finnish Model. Oxford University Press.

Claeys, G. (2017). Dystopia: A Natural (1st edition). Oxford University Press.

De Foigny, G. (1676). A New Discovery of Terra Incognita Australis.

Digivisio 2030. (n.d.). Digivisio 2030. Digivisio 2030. Retrieved August 16, 2023, from https://digivisio2030.fi/

Digivisio 2030. (2021a). Digivisio 2030 -hankkeen esittely [Digivisio 2030 project description]. https://wiki.eduuni.fi/download/attachments/187242368/Digivisio2030_06_2021.pdf

Elfert, M., & Ydesen, C. (2023). Global Governance of Education. The Historical and Contemporary Entanglements of UNESCO, the OECD and the World Bank. Springer.

Eskelinen, T. (Ed.). (2020). The Revival of Political Imagination: Utopia as Methodology. Zed Books.

European Commission. (2015). A Digital Single Market Strategy for Europe. European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/api/files/attachment/8210/DSM_communication.pdf

European Commission. (2020). Digital Education action Plan 2021-2027 Resetting education and training for the digital age. Commission Staff Working Paper. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52018DC0022&from=EN

European Commission. (2021). 2030 Digital Compass: The European way for the Digital Decade. European Commission.

Fairclough, N. (2013). Critical Discourse Analysis: The Critical Study of Language (2nd edition). Routledge.

Freeden, M. (2015). Liberalism: A very short introduction (1st edition). Oxford University Press.

Freire, P. (2014). Pedagogy of hope: Reliving pedagogy of the oppressed. Bloomsbury Academic.

Fromm, E. (1968). The Revolution of Hope: Toward a Humanized Technology. Harper & Row.

Gadamer, H.-G. (2004). Truth and Method (J. Weinsheimer & D. G. Marshall, Trans.; 2nd, rev. ed ed.). Continuum.

Gordin, M. D., Tilley, H., & Prakash, G. (Eds.). (2010). Utopia/dystopia: Conditions of historical possibility. Princeton University Press.

Hall, S. (2011). The Neo-Liberal Revolution. Cultural Studies, 25(6), 705–728. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502386.2011.619886

Holborow, M. (2015). Language and neoliberalism. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

Holborow,M.(2016). Neoliberal Keywords, Political Economy and the Relevance of Ideology. A Journal of Cultural Materialism, 14, 38–53.

Hout, W. (2007). The Politics of Aid Selectivity: Good Governance Criteria in World Bank, U.S. and Dutch Development Assistance. Routledge.

Huxley, A. (1932). Brave New World. Chatto & Windus.

Komljenovic, J., Williamson, B., Eynon, R., & Davies, H. C. (2023). When public policy ‘fails’ and venture capital ‘saves’ education: Edtech investors as economic and political actors. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767724.2023.2272134

Krejsler, J. B. (2019). How a European ‘Fear of Falling Behind’ Discourse Co-produces Global Standards: Exploring the Inbound and Outbound Performativity of the Transnational Turn in European Education Policy. In C. Ydesen (Ed.), The OECD’s Historical Rise in Education (pp. 245–267). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-33799-5_12

Kreps, S., & Kriner, D. (2023). How AI Threatens Democracy. Journal of Democracy, 34(4), 122–31. https://www.journalofdemocracy.org/articles/how-ai-threatens-democracy/

Kumar, K. (2003). Aspects of the western utopian tradition. History of the Human Sciences, 16(1), 63–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/0952695103016001006

Lakkala, K. (2020). Disruptive Utopianism: Opening the Present. In K. Eskelinen (Ed.), The Revival of Political Imagination: Utopia as Methodology (pp. 20–36). Zed Books.

Langdridge, D. (2007). Phenomenological Psychology: Theory, Research and Method. Pearson Prentice Hall.

Levitas, R. (2010). The Concept of Utopia (2nd edition). Peter Lang.

Levitas, R.(2013). Utopia as Method: The Imaginary Reconstruction of Society. Palgrave Macmillan.

Marks, P., Wagner-Lawlor, J. A., & Vieira, F. (Eds.). (2022). The Palgrave handbook of utopian and dystopian literatures. Palgrave Macmillan.

McNay, L. (2009). Self as Enterprise: Dilemmas of Control and Resistance in Foucault’s The Birth of Biopolitics. Theory, Culture & Society, 26(6), 55–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276409347697

Meretoja, H. (2018). The Ethics of Storytelling: Narrative Hermeneutics, History, and the Possible. Oxford University Press.

Microsoft. (2018). Transforming Education: Empowering the students of today to create the world of tomorrow. https://news.microsoft.com/wp-content/uploads/prod/sites/66/2018/06/Transforming-Education-eBook_Final.pdf

Microsoft & McKinsey & Company. (2019). The class of 2030 and life-ready learning: The technology imperative. A summary report. Microsoft and McKinsey & Company.

Ministry of Education and Culture. (n.d.). Vision for higher education and research in 2030. Ministry of Education and Culture. Retrieved May 10, 2022, from https://okm.fi/en/vision-2030

Ministry of Education and Culture. (2017). Korkeakoulutus ja tutkimus 2030-luvulle. Taustamuistio korkeakoulutuksen ja tutkimuksen 2030 visiotyölle. [Vision for higher education and research in 2030. Background document to the vision process.] https://minedu.fi/documents/1410845/4177242/visio2030-taustamuistio.pdf/b370e5ec-66d3-44cb-acb9-7ac4318c49c7/visio2030-taustamuistio.pdf

Ministry of Education and Culture. (2019). Higher Education and Research Until the 2030s: Roadmap for Implementing Our Vision. https://okm.fi/documents/1410845/12021888/Vision+2030+roadmap/6dfddc6f-ab7a-2ca2-32a2-84633828c942/Vision+2030+roadmap.pdf

Ministry of Education and Culture. (2021). Digivision 2030 project implementation in higher education institutions launched. https://okm.fi/en/-/digivision-2030-project-implementation-in-higher-education-institutions-launched?languageId=en_US

Morris, W. (1890). News from Nowhere. Commonweal Journal.

OECD. (2019). OECD Skills Outlook 2019: Thriving in a Digital World. OECD. https://doi.org/10.1787/df80bc12-en

Orwell, G. (1949). 1984. Secker & Warburg.

Popper, K. (2013). The Open Society and Its Enemies (Original work published 1945). Princeton University Press.

Poutanen, M., Tomperi, T., Kuusela, H., Kaleva, V., & Tervasmäki, T. (2022). From democracy to managerialism: Foundation universities as the embodiment of Finnish university policies. Journal of Education Policy, 37(3), 419–442. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2020.1846080

Rancière, J. (1991). The Ignorant Schoolmaster. Five Lessons in Intellectual Emancipation (K. Ross, Trans.). Stanford University Press.

Rautalin, M. (2012). Domestication of International Comparisons: The role of the OECD Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) in Finnish education policy [Tampere University]. https://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-951-44-9278-5

Ricœur, P. (1984). Time and narrative. 1 (K. McLaughlin & D. Pellauer, Trans.). The University of Chicago Press.

Rinne, R. (2006). A model pupil? Globalization, Finnish Educational Policies and Pressure from Supranational Organizations. In Kallo, J. & Rinne, R. (Eds.). Supranational Regimes and National Education Policies (pp. 183–215). Turku: Finnish Educational Research Association.

Stewart, E., & Roy, A. D. (2014). Subjectification. In T. Teo (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Critical Psychology (pp. 1876–1880). Springer New York. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-5583-7_358

Teräs, M., Suoranta, J., Teräs, H., & Curcher, M. (2020). Post-Covid-19 Education and Education Technology ‘Solutionism’: A Seller’s Market. Postdigital Science and Education, 2(3), 863–878. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-020-00164-x

Virilio, P., & Richard, B. (2012). The Administration of Fear (A. Hodges, Trans.). Semiotext(e).

Wells, H. G. (2009). A Modern Utopia (Original work published 1905). The Floating Press.

Ydesen, C. (Ed.). (2019). The OECD’s Historical Rise in Education: The Formation of a Global Governing Complex. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-33799-5

- “Sivistys” could be translated as “learning”, “civilization” or “culture”. Perhaps still, it is closer to the German term “building”, which means more broadly “self-cultivation” or growing to personhood. ↵