2. Galatea’s Revenge on Pygmalion. Women, Democracies, and Earth: Same Colonial Oppressions, Same Decolonial Struggles!

Gina Thésée

Abstract

Democracy is in crisis, it seems. In this centuries-old eco-geopolitical era, the Colonialocene, we are experiencing colonial realities that are petrifying us, turning us into statuesque. First, the denial of women’s rights, the rise of masculinism, and the expression of toxic masculinity. Second, the fundamentals of democracy are openly flouted by autocrats exercising their brutality that is at once racist, patriarchal, capitalist, and extractivist. Third, the environment is showing symptoms of a disruption in the ecological balance that is contrary to the conditions of life on Earth. In this global context, a triple war is being waged: against Women, against Democracies, and against the Earth. To problematize this triple war, the “Myth of Pygmalion” is analyzed as a “model” of a total power relationship of the masculine over the feminine. The analysis is based on artistic adaptations of the myth presented in the West over the centuries. The myth is deconstructed within a theoretical framework inspired by decolonial feminisms and then revisited by exploring the dynamics of the domination of “Pygmalion-Coloniality” over Galatea, the latter embodying at the same time Women, Democracies, and the Earth. Is democracy in crisis? No. Democracy is, quite simply, as it has been, petrified, sculpted, and statufied with/by/in/for colonial modernity. Galatea, Women, Democracies, and the Earth face the same colonial oppressions; their revenge comes through their common decolonial struggles for their emancipation and for living well together on Earth.

Keywords: Galatea; Pygmalion; Democracies; Women; Earth; Coloniality; Decolonial Feminism; Pygmalion-Coloniality; Galatea-Women/Democracies/Earth; Decolonial Democracies.

Introduction

Earth Democracy connects people in circles of care, cooperation, and compassion instead of dividing them through competition and conflict, fear and hatred.

Vandana Shiva (2005)

In everything, in every place, at all times, in all circumstances and with whomever, when women are in danger, democracies are also in danger, as is the Earth itself. When democracies are in danger, women are also in danger, as is the Earth itself. Likewise, when the Earth is in danger, women are in danger, as are democracies. The quality of a democracy is measured by the quality of the living conditions of the women who live there and by the quality of their ecological environment (Tamés, 2022). Globally, women, democracies, and the Earth experience the same relations of domination and face the same dynamics of aggression/oppression. Women, Democracies, and the Earth, the same colonial oppressions, and therefore, the same urgency for emancipation and decolonial struggles.

Vandana Shiva, the Indian scientist and activist, has theorized the triple articulation of the oppressions experienced by women, democracies and the Earth with “Ecofeminism” from its decolonial perspective. In her book Earth Democracy: Justice, Sustainability and Peace (2005), her denunciations are numerous: i) ecosocial injustice; ii) excesses of positivist science; iii) rupture of humans with Nature; iv) control over Nature and its capitalist commodification; v) notion of infinite progress; vi) bio-piracy; vii) democracy excluding the Earth. She proposes to move from a system of death to a system of life by cultivating living communities (from Patriarchy to Feminism), living cultures and economies (from capitalism to the common good), and living democracies (from ecosocial injustice to ecosocial justice). Earth Democracy invites us to reinvent democracy, to imagine a Life-democracy in action in Earth-democracies and Women-democracies. Pachamama, our Mother Earth (Terra-Madre), suffers from multiple acts of violence that have given rise to the various ecosocial ills we are currently experiencing. Gaia, our Life-Earth, suffers from multiple acts of violence that have given rise to the many political crises we are currently experiencing. Oïkos, our Earth-Home, faces multiple acts of violence that have given rise to the main threat, climate change.

Reading about the world’s ills, I set out to find meaningful concepts that could heal our times. However, the words for reading, feeling, saying, and healing the world, starting from the world below, the one described in The Wretched of the Earth (Fanon, 1970), are de facto invalidated/disqualified. The words for inhabiting the world and the Earth (Sarr, 2013; Taubira, 2017) and those for building democracy together are confiscated and debased. So, in this world of multiple and chronic crises, what word concepts will keep hope alive for the generations of today and tomorrow? (Carrière, 2021). Isn’t the purpose of such an exercise to glimpse a small green shoot of hope rising from the ashes of the volcanic magma of our time, in itself utopian? Yes! According to Jacques Delors, Utopia is “necessary to enable humanity to progress towards ideals of Peace, Social Justice, Freedom”, because “how can we learn to live together in the ‘global village’ if we are not capable of living in our natural communities of belonging: the nation, the region, the city, the village, the neighborhood? Do we want to, can we [and know how to] participate in community life, that is the central question of democracy.” (UNESCO, 1996, p. 15). Reinhold Niebuhr (1986) “Man’s capacity for justice makes democracy possible, but his penchant for injustice makes democracy necessary.[1]“

How can we truly build democracy together in this world of brutality, fire, blood and fury, steeped in centuries-old colonialism, where a triple war is openly waged against women, against democracies and against the Earth itself (Mother Earth, Earth Life, Earth Home)? The theory of coloniality (Maldonaldo-Torres, 2023, 2016; Lugones, 2019; Dussel, 2012; Mignolo, 2007; Quijano, 2000, 1992) allows us to analyze the situation by highlighting the dynamics of domination within the matrix of coloniality. Like Ferdinand (2019), who invites us to re/think ecology from decolonial perspectives, I propose to re/think democracies from decolonial perspectives.

To problematize this triple war waged on a global scale, the “Myth of Pygmalion” is used as a “model” of the total power relationship at stake. The myth is analyzed based on certain literary, pictorial, sculptural, theatrical or cinematographic adaptations presented in the West over the centuries. It is deconstructed within a theoretical framework inspired by decolonial ecofeminism. The myth is revisited by exploring the dynamics of domination/oppression of “Pygmalion-Coloniality” on its sculpture, Galatea, which embodies women, democracies and the Earth at the same time. I develop my reflection in the following sections: 1) The context: the colonialocene; 2) Which democracies? Colonial democracies; 3) A model: the “Myth of Pygmalion”; 4) The Pygmalion myth revisited: Pygmalion-Coloniality; 5) Galatea’s Revenge on Pygmalion-Coloniality; 6) For a Decolonialized Democracy.

The context: the eco-geopolitical era of the Colonialocene

For the First Peoples in Abya Yala[2], the year 1492 marks the beginning of the colonial earthquake caused by the invasion of their territories by European kingdoms, mainly Portugal, Spain, England, France, and the Netherlands. From the beginning, colonization took brutal, institutionalized forms: the total domination of peoples, the enslavement of people, the capitalist exploitation of resources, and tricontinental trade. According to geochronologist Michel Lamothe, “In the history of the Earth […], transitions from one era to another are often characterized by catastrophic events” (quoted by Bourdon, 2024). In this sense, since the end of the 15th century, the colonization of Abya Yala by European kingdoms has marked the beginning of a new eco-geopolitical era whose dimensions are at once political, military, economic, scientific, technical, religious, social, cultural, and educational: “the Colonialocene.”

This neologism is similar to the “Anthropocene” proposed in the social sciences but contested in the geological sciences. The “Anthropocene” refers to the conclusion of scientists who recognize that human activity is the main cause of the acceleration of global warming (Gibbard, 2013). Although it cannot be considered a geological era in the strict sense of the term, “the Anthropocene” designates the geological event caused by the considerable impact of human activities on the environment, especially since the Industrial Revolution (early 19th century) and since the capitalist overproduction of objects following the Second World War (mid-20th century). The activities of agriculture, urbanization, deforestation and pollution have caused extraordinary changes on Earth.” (NHM[3], undated). Through the accumulation of key markers, a sedimentary imprint leaves observable and measurable traces in ecosystems. The Anthropocene also refers to the period of the event (Gibbard cited by Bourdon, 2024).

The Anthropocene is approached according to its human, general and universal character, in other words, from the perspective of the colonizer. However, the human activities that are at the origin of the Anthropocene have not been carried out with the same intensity or with the same consequences by all humans on Earth. The vast majority of humans find themselves on the negative side of the axis of power relations, that is to say, on the side of the colonized in a network of relations with the colonizer, where they still suffer from the colonial situation (Memmi, 2003). From the perspective of the colonized in Abya Yala, who have suffered and are still suffering the ravages of the “Anthropocene” (slavery, genocides, extractivism, ecocides) and its consequences (pollution, climate disruption, environmental disasters), the current eco-geopolitical era, since 1492, is the “Colonialocene”.

I use the term “Colonialocene” in reference to Ferdinand’s (2019) concept of “Colonial Inhabiting,” although this author does not elaborate on it in his book. However, his detailed description and analysis of colonial inhabiting in the context of the colonized and enslaved Caribbean world gives the Colonialocene the foundations of an eco-geopolitical era, just as the Anthropocene does. Colonial inhabiting consecrates the resource-territory as a “wordless land,” a “motherless land,”[4] an Earth without life. He associates “colonial inhabiting “with the principled gesture of colonization: “the act of inhabiting. […] The European colonization of the Americas violently implemented a particular way of inhabiting the Earth” (Ferdinand, 2019, p. 46). By analyzing “colonial living,” Ferdinand highlights: its foundations (land grabbing, massacres, clearing); its principles (geography, exploitation of nature and altericide); its forms (private property, plantations, exploitation of humans, enslavement) (Ibid., pp. 49, 52, 54). The Colonialocene designates the eco-geopolitical era that began with the colonization of Abya Yala at the end of the 15th century and has lasted ever since. The Colonialocene also designates the enterprise that consisted of radically creating “colonial living.” The “Colonialocene” allows us to approach climate disruption and current environmental disasters as events whose epicentre is located in the centuries-old colonial enterprise.

Several concepts emerged in the literature at the beginning of the 20th century to name/describe the current eco-geopolitical era: “Androcene”; “Anthropocene”; “Capitalocene”; “Necrocene”; “Negrocene”; “Patriarcapitalocene”; “Plantationocene”; “Poubellocene”; “Thanatocene”; “Westernocene”. These concepts are approached as synonyms, and sometimes with more nuance. Some authors use them as decolonial tools while others criticize, contest, or reject them. Avoiding these debates, I approach these concepts as so many dimensions of the “Colonialocene”. This allows me to reveal both the excesses of Western colonial modernity and the ravages of the colonial enterprise that took root and developed in the matrix of the centuries-old colonial enterprise (Thésée, 2006). I analyze the “Colonialocene” in its multidimensionality through the ten concepts cited above.

1) Androcene. In its sex and gender dimension, it is the admission that the Anthropocene is masculine, that “the analysis of the environmental crisis requires […] challenging the ideals associated with dominant masculinities” (Ruault et al., 2021) and that the responsibility for the degradation of life on Earth lies with a certain type of “Andres” masculinity (Ruault et al., 2021; Campagne, 2017);

2) Anthropocene. In its anthropological dimension, it is the human takeover of Nature and its significant, ecocidal imprint (Gibbard, 2013);

3) Capitalocene. In its economic dimension, it is the system of power, profits, production and accumulation of capital that has become the very fabric of life and exchanges for more than four centuries (Moore, 2017; Campagne, 2017);

4) Necrocene. In its political dimension, it is an ecological anarchism (eco-anarchy) expressing a loss of reference points, rules and meaning, and sowing death in the shared house of life “Oïkos” (Clark, 2019);

5) Negrocene. In its geo-demographic dimension, it is the politics of the hold, of the subalterns, of the people at the bottom of the bottom, the damned, the oppressed who have made women, the colonized world and the Earth “the Negroes of the world” (Ferdinand, 2019);

6) Patriarcapitalocene. In its family dimension, it is the accumulation of capital/power and its transgenerational transmission by men, from father to son (Campagne, 2017);

7) Plantacionocene. In its institutional dimension, it is the eco-social engineering of the plantation for the exploitation of resources and people (Wolford, 2021; Ferdinand, 2019);

8) Poubellocene. In its environmental dimension, it is the use of colonized territories as (“natural” places for dumping the colonizers’ “waste”) (Armiero, 2024);

9) Thanatocene. In its spiritual dimension, it is “Thanatos” which is expressed by death drives, destruction and degeneration of life. These death drives are the driving force of a culture of war, which operates massive destruction of communities and ecosystems for the benefit of the military-industrial complex (Bonneuil & Fressoz, 2013);

10) Westernocene. In its epistemological dimension, it is the creation of knowledge within the hegemonic framework of Western thought: predatory, dualistic, reductionist, and individualistic (San Román & Molinero-Gerbeau, 2023).

“Democracy”? A Colonial Democracy(ies)

From its origins in ancient Greece, democracy has been a decoy. Athenian democracy only concerns free men; women and slaves are immediately excluded from the “demos” (people) and the “kratos” (power). The same is true in modern democracies in Abya Yala, where the right to vote, considered one of its fundamentals, was long denied to women, Indigenous peoples, and Black people. Obtaining the right will be achieved through long-term struggles by each group. Paradoxically, the “people” do not hold real power; they delegate their power to representatives and are dispossessed of it as soon as the results of the vote are known.

“Democracy” is in crisis, it seems. Democracy is going from crisis to crisis: crisis of representative democracy; crisis of disaffection for the electoral vote by young people; crisis of democratically elected regimes that have become autocratic; crisis of democratic institutions; crisis of information and media as a fourth estate; crisis of the undemocratic nature of virtual spaces; crisis of wars and lawless zones between democracies; major eco-social crisis. However, the question arises: “Is democracy really going through a crisis?” (IPU[5], 2021). According to the Inter-Parliamentary Union, democracy would be the only system capable of self-correction. In its recent history, modern democracy has gone through several crises, even cycles of crises that began at the end of the 19th century with universal suffrage, followed by the workers’ movement, followed by the First World War and the economic crisis of 1929 (Gauchet, 2008). The author sees democracy as the all-encompassing concept of modernity; he places the present crisis within the long term of a multi-secular phenomenon.

This centuries-old phenomenon would be the revolution caused by the passage of the system of social structuring by human heteronomy, rules external to humans and mediated by religions, a system of social structuring by human autonomy or the internal rules of humans, which they determine themselves. Modernity would be this global revolution, which, since the 16th century, has seen the tearing away of modern human societies from religious structuring. For five centuries, all the great revolutions, whether political, scientific, industrial, economic or social (and let us add, the technological and techno-digital revolutions), can be reduced to this same common denominator, that of the revolution of the structuring and political organization of societies by human autonomy. According to Gauchet (2008, p. 62), the passage from human heteronomy to human autonomy takes place along three interrelated axes: i) politics, in the form of a new collective entity, the “nation-state”; ii) law, as a principle of legitimacy in the organization of the “nation-state” or the “rule of law”; iii) history, as a voluntarist futuristic orientation of economic development within the nation-state. Paradoxically, the transition to human autonomy would have given rise to a “Crisis of growth of democracy” and a “disconnection of collectives”. Surprisingly, Gauchet (2008), in his detailed analysis of the crisis of democracy (along three axes: politics, law and history), which has lasted for five centuries, the brutal colonial enterprise carried out by European kingdoms and then nation-states in the world is neither explained nor named nor even mentioned. Epistemological blindness or coloniality or both?

The transition from human heteronomy to human autonomy has permanently transformed the relationships between humans and… space, time, the world, Nature, self and the Other. Identities, otherness and the multiple layers of citizenship are profoundly affected. During this transition, several variations coexist: from the absolute power of a single, masculine, immanent, invisible and transcendent being (Theocracy), to the quasi-absolute power of a single, masculine being, the incarnation of “God” on Earth, the “King” (Monarchy), to the supposed power of all represented by a collective being, the “nation-state”, formed of men in the vast majority (Democracy). The latter, democracy, aims to be an “impersonal, abstract and disembodied” governing machine, operated mainly by men, an “androcracy”. The nation-state where “Democracy” crystallizes is being shaken from all sides, because power, of an unprecedented nature, scale and acceleration, is passing into the hands of a clique of individuals from the technological sphere, forming a sort of andro-techno-capitalist, misogynistic and racist oligarchy, which operates rather in anomie (absence of rules) and which concentrates all powers: technological power (deployment of digital technologies); scientific power (development of technosciences); ecological power (extraction and overuse of natural resources for technosciences); ethnological power (domination and exploitation of colonized, subalternized peoples); economic power (grabbing of technological wealth, accumulation of capital); social power (scope and omnipresence of technosocial networks); cultural power (usurpation of cultural forms by artificial intelligence (AI); media power (technical distortion of information, control over the media); cognitive power (control of techno-cognitive teaching-learning methods); political power (disintegration of the nation-state into a Techno-state). Notwithstanding the particularities of those in power over the centuries, the transition from human heteronomy to human autonomy, and now to human anomie, could only take place by being part of a paradigm that provided all the levers (political, economic, ecological, scientific, technological, epistemological, educational, cultural) that were necessary for the actors of this revolution. This “nomic[6]” Revolution, which dates from the 16th century, was accompanied by the birth of a new paradigm: the paradigm of coloniality.

Modern democracy, the all-encompassing concept of (Western) modernity and the political shaping of human autonomy (Gauchet, 2008), is inextricably linked to the centuries-old colonial enterprise carried out by European kingdoms in Abya Yala territory and deeply imbued with the coloniality that results from it. In this sense, is democracy in crisis? No; democracy is not in crisis. Democracy is, quite simply, as it was conceived, constructed, and conducted within the matrix of centuries-old coloniality during the eco-geopolitical era of the Colonialocene. Modern democracy is soluble in this coloniality. It is a colonial democracy.

In colonial democracy, the fundamental principles of democracy are not (necessarily) called into question, because they do not have to be, since these fundamental principles themselves were conceived and developed in the same matrix of coloniality. There is therefore no antinomy between democracy and colonial democracy; it is the same political regime. That said, I do not want to deny the importance of democracy, which, according to Winston Churchill, even if imperfect, turns out to be, despite everything, the least bad political system for our world. Notwithstanding this admission, what can be done in the face of colonial democracies, indecent and indifferent, self-righteous and arrogant, brutal? Singular or plural, colonial democracy(ies) turn out to be, at best, imagined, idealized, reified and then desacralized political creatures. In their daily banality, colonial democracies are compatible with multiple forms of violence: domestic, family, social, environmental, economic, ecological, political, and military. At this very moment, this violence is culminating, with complete impunity, in feminicide, genocide/ethnocide, economicide, ecocide. Is this how we want to live well together on Earth? Colonial democracy does not keep the promises of a possible and necessary Utopia. Is democracy an unfinished project or an unrealized project? Dussel (2022) answers this question by developing a plea for a profound transformation of the values, fundamental principles, and social praxis of the as-yet-unrealized democracy.

The “Myth of Pygmalion”, according to artistic adaptations

“Pygmalion” is one of the most well-known myths. Originating from Greco-Roman mythology, it has been popularized over the centuries in the West in several cultural works, including literature, painting, sculpture, theatre, musicals, and cinema. In psychoeducation, this myth is also associated with a phenomenon called the “Pygmalion Effect,” which depicts the teacher and their student in their pedagogical relationship.

Like other myths of Greco-Roman mythology, the “Myth of Pygmalion,” by the author Ovidius (1st century) in the tenth book of his work Metamorphoses, presents us with two archetypes, masculine and feminine. Pygmalion, a solitary, misogynistic man, flees women since they all turn out to be villains. He sculpts a statue of a woman from marble, the purest ivory white, which reveals itself to him as the perfect “feminine creature.” Her pure whiteness and statuary perfection are so aesthetic that he falls madly in love with her; “She has the appearance of a real young girl, one could believe her alive” (Berthier & Boutard, 2016, p. 164). Is she made of stone or flesh, his beloved work? It doesn’t matter; the fire of his passion for her prevails and guides his gestures on her ivory flesh. Venus, the goddess of love, having interceded on behalf of the sculptor, and not the sculpture, the work is then animated by the “warm breath of life” (Ibid., p. 169), it comes to life, reveals itself as the ideal “feminine creature” and is subject to the obsessive feelings of its sculptor-creator. After a period of nine moons, the nameless feminine creature gives birth to their daughter: Paphos. Subsequently, she is given a name, “Galatea”, which literally means “the girl with skin white as milk”.

Due to its multiple artistic adaptations and reinterpretations over the centuries, the Myth of Pygmalion reveals both its cultural polysemy and its permeation into Western culture (Lesec, 2008). On the surface, this myth is presented as the relationship between a male artist and his work, his female object. This is how it has been the subject of various artistic adaptations, the most well-known of which have been proposed by male artists, as shown in the selection by Berthier and Boutard (2016).

- In the 17th century (1662), the French playwright Molière took the opposite view of the message of the myth with the play The School for Wives, where a misogynistic man with possessive, selfish and cynical behaviour is portrayed in his domination of the female character (Berthier & Boutard, 2016, p. 167).

- In the 17th century (1678), Jean de la Fontaine published, in his Fables, a rather disturbing fable, “The Statuary and the Statue of Jupiter.” This time, Pygmalion falls in love with Venus, his marble daughter. Incest is mentioned: “Pygmalion became the lover of Venus, of whom he was the father.” (Latour, 1996).

- In the 18th century (1762), the Swiss philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau portrayed a “Pygmalion” artist living a delirious and dramatic relationship with his statuary work, which is now called Galatea. (Mediterraneans, undated).

- In the 19th century (1819), the French painter, Anne-Louis Girodet, painted the painting Pygmalion in Love with his Statue. The neoclassicism of the painting reflects the quest for ideal beauty and the exaltation of feelings. This painting is considered a precursor of the Romantic period (Louvre, 2019).

- In the 19th century (1846), the French writer Honoré de Balzac, in the short story entitled The Unknown Masterpiece / The Human Comedy, highlights the attachment, even the obsessive emotional torment, that an old painter has with his work-woman, whom he wants to be beautiful and faithful. This work inspired the film La Belle Noiseuse (1991). (Berthier & Boutard, 2016, p. 168).

- In the 19th century (1857), The Oval Portrait by the American poet, Allan Edgar Poe, translated into French by Baudelaire, reverses the metamorphosis of the myth by proposing a real, anonymous young woman, a living model for her husband’s painting, who dies by being transformed into this inanimate portrait of her in an artistic ecstasy of her painter-husband who sees her alive “it is Life itself.” (Berthier & Boutard, 2016, p. 178).

- In the 19th century (1890), the famous French painter, Jean-Léon Gérôme, painted a painting entitled Pygmalion and Galatea showing an embrace between two figures. In the center of the painting, the sculpture, shown from behind, comes to life; the upper part of its body is already human, while its legs are still frozen in stone (Berthier & Boutard, 2026, p. 179).

- In the 20th century (1912), Irish playwright George Bernard Shaw staged his play Pygmalion, a comic satire, in London. In it, he criticized English society, steeped in classism, where social classes were circumscribed and impermeable, and distinguished from each other by determining social markers, such as behaviour and the use of the English language. The male character, a misogynistic, arrogant, and rude professor, shapes the female character while humiliating her. The young florist will take her revenge by marrying the professor’s friend.

- In the 20th century (1972), the American author Charles Bukowski published a short story, The Fucking Machine. Elements of the Pygmalion myth are found there; however, the author adopts a provocative stance by describing an unruly woman-passion, apparently free of her sexual impulses. His provocation turns out to be a decoy, since it is in fact a machine created to satisfy the sexual fantasies of its creator; the latter believes in the reality of his creature, a machine-woman, a woman-machine?

- In the 20th century (1964), one of the most famous adaptations of the “Myth of Pygmalion” is the musical comedy followed by the Oscar-winning film My Fair Lady by director George Cukor. The director uses Shaw’s text, but the title highlights the female character, albeit ambiguously (My), and the ending of the film is distorted. The male character sculpts, shapes and humiliates the female character as he pleases, which will not prevent the latter from falling in love with him despite the domination she suffers.

- In the 20th century (1991), the film La Belle Noiseuse by French director Jacques Rivette won the Grand Jury Prize at the Cannes Film Festival. In this adaptation of Balzac’s short story “The Unknown Masterpiece,” the painter, prey to a haunting memory, paints the body of his model, the young Marianne, from behind, to avoid her face. The painting La Belle Noiseuse transforms a woman into a faceless body, without personality, without identity. Could this be an “anti-feminist” interpretation[7] of the myth? (Once Upon a Time in Cinema, 1991).

- In the 20th century (1990), in another adaptation of Shaw’s play, director Gary Marshall offers a romantic comedy with the film Pretty Woman. It is about a young and beautiful prostitute and a successful but disillusioned businessman, set in the context of Los Angeles. Once again, the male character sculpts, manufactures, and transforms the female character into an ideal creature according to his own wishes.

- In the 20th century (1999), in Montreal, at the Rideau-vert, in another adaptation of Shaw, the play was translated by Antonine Maillet and directed by Françoise Faucher; two women. Pygmalion is presented as a masterpiece by Shaw, a romance in five acts, where behind the mask of conventions and prejudices, we find the comedy that serves to denounce the ridiculous (Revue théâtre du Rideau-vert, 1999).

The myth of Pygmalion remains very present in Western classical and popular culture. What is the significance of this longevity? The two archetypes, masculine (Pygmalion) and feminine (Galatée), remain prevalent in female-male relationships and in their reciprocal relations. Studies of the myth have been conducted in various disciplinary fields: in linguistics, in the expression “a Pygmalion Man”; in art, in “The relationship of the artist to his work”; in romantic literature, the feeling of love and sexuality; in sculpture, sculptural aesthetics, the simulation of flesh in ivory; in art history, the freedom in adaptations, recreations, rewritings and reinterpretations of works; in sociology, the intersectionality of gender and social class relations; in psychology, fabricated and appropriated otherness. In education, the positive or negative “Pygmalion Effect” (Berthier & Boutard, 2016). By revealing parts of the myth that have remained in the shadows, the artistic adaptations of “Pygmalion” reveal obliterated parts of the societies in which they take place (Lesec, 2008).

Other works that I have not presented above are also inspired by the “Pygmalion” myth. In her article The Fantasy of Pygmalion, the psychoanalyst Sophie de Mijolla-Mellor (2008) highlights works by the Marquis de Sade, Nabokov, Petrarch, Dante and Botticelli, where adolescent figures are exposed to what she calls “the madness of pedophile predator” (p. 817). Thus, Story of O, Lolita, Laure, Beatrice or the marble nymph are very young girls who personify Galatea, the sculpture of Pygmalion. In this myth and its various adaptations or interpretations, the ethical, legal, psychological, psychoanalytical, and even psychopathological aspects are, to say the least, troubling and worrying (Mijolla-Mellor, 2008). However, when it comes to artistic adaptations of the myth, this is not the case; a relative banality coated in romanticism against a backdrop of a relationship of domination welcomes the works[8]. Celebrated, rewarded and transmitted from generation to generation, these works contribute to maintaining the status quo of representations of domination of the feminine and predation of girls by men. Between the (passive) indifference and the (active) complicity of men in the face of violence experienced by women, how can we understand the construction of men’s indifference?

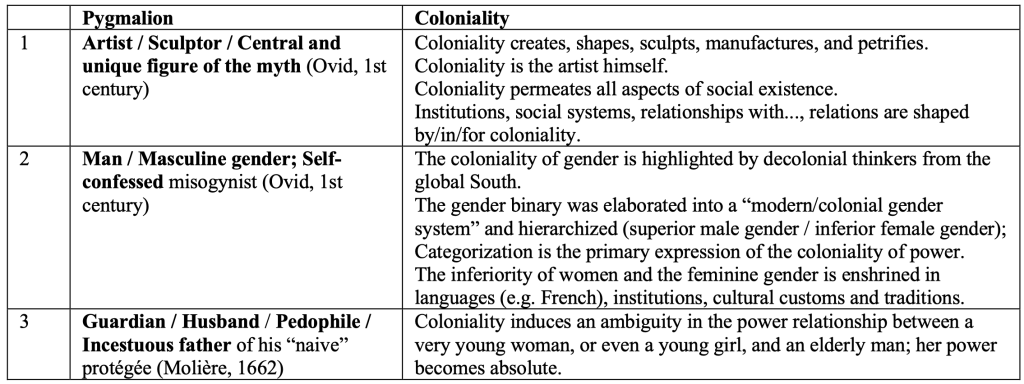

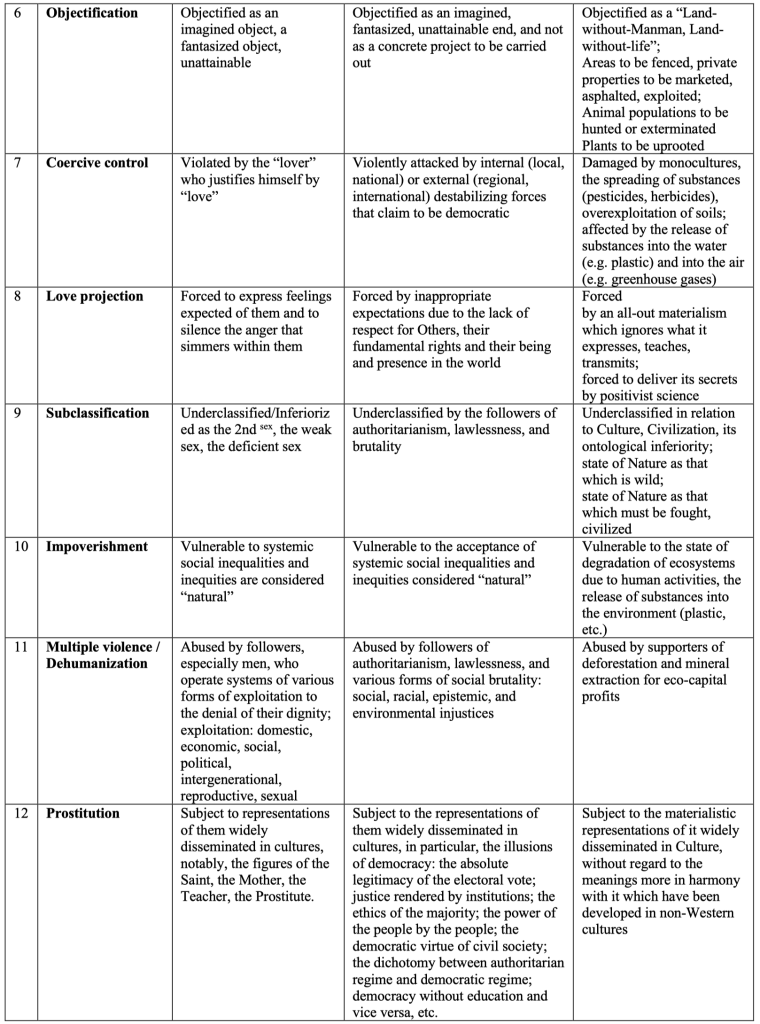

The myth of Pygmalion revisited: Pygmalion-Coloniality

In the works presented above, the authors are well-known male artists. Apart from Molière’s critical adaptation in The School for Wives, few interpretations or adaptations of the “Pygmalion” myth have dared to criticize the representation of the female character. No adaptation has dared to undo the power relationship between the two characters; no one has denounced the total domination, both symbolic and effective, of the feminine by the masculine, which is presented as being “natural”. In the 20th century, artistic adaptations go further in the dynamics of domination by associating elitism (Pygmalion in London); social class relations (My Fair Lady); ambiguous relationships between women (La Belle Noiseuse); combined relationships of sex, money and seduction (Pretty Woman); sexual relations (The Fucking Machine), romance (Pygmalion in Montreal).

It is not surprising that the myth of Pygmalion has been the subject of so many adaptations and interpretations. On the surface, this myth embodies the artist’s fantasy relationship with his work. In fact, it is the centuries-old model of woman as she has been sculpted, petrified, and statufied into a feminine ideal, whose beauty is the only characteristic, essentially a woman-object, devoted to the services, fantasies, desires, and interests of her creator. In cinema, this myth illustrates, very concretely, the fantasy world of the male director projected onto a female actress, who literally becomes his property (muse, work, sculpture, object, or machine). In the West, what cinematographic works made by male directors echo, explicitly or implicitly, the myth of Pygmalion? I dare to hypothesize that a large number of films by male directors are in reality stagings of their relationships with women, fantasized, imagined and/or experienced through acting out. Doesn’t the brilliance of the “Me Too” movement echo the concrete prevalence of this myth in the artistic sphere and in society in general? Like other Greco-Roman myths, the “Pygmalion” myth has profoundly shaped male thought, on the one hand, in the dynamic of domination of the man-sculptor over the woman-sculpture, and on the other hand, in the social representations of “the ideal woman”, “Galatea”, created, sculpted, reified into a fetish object and subjected to the domination-obsession of the man-creator, her god. In 1971, French film actress Delphine Seyrig told Radio-France that it was important for women to start talking about themselves, and not as men had portrayed them. She was one of the women who demanded their emancipation from the representations of male directors and believed that this would be achieved through the arrival of female directors in film culture (Caparros, 2024).

In Table 2.1 below, I revisit the myth by sketching the features of the “real” male character that I call: “Pygmalion-Coloniality”.

Theoretical framework of decolonial feminism

The Argentinian feminist philosopher Maria Lugones (2019) had as her leitmotif to “understand the worrying indifference” of men in the face of systemic violence against women (p. 46). She wanted to understand the construction of this indifference, which constitutes a significant obstacle to women’s struggles at the intersection of issues of race, class, gender, and sexuality. She interweaves two theoretical fields: i) the theory of the coloniality of power of Aníbal Quijano (1992, 2000, 2007) and other thinkers of the decolonial movement (Maldonado-Torres, 2016; Dussel, 2012; Mignolo, 2007); ii) the decolonial feminisms of Abya Yala (Espinoza Miñoso et al., 2022). For Quijano (2000, p. 53), “race” constitutes “the fundamental modality of universal social classification of the world population. The production of gender, as well as other relations of domination and exploitation […], are constitutive of the coloniality of power, generally, distally.”

By adopting a more specific, proximal perspective on the coloniality of power, Maria Lugones analyzes the “modern/colonial gender system” to better understand the consequences of men’s indifference-complicity with this destructive system. From her decolonial feminist perspective, gender is not a simple category of the coloniality of power. The making of gender occurs at the intersection of racialization and genderization, both central and mutually constituted in the coloniality of power. Her theory of the coloniality of gender was born from this articulation (Falquet, 2021).

Decolonial feminism is situated in the territorial context of South Abya Yala and in the historical context of colonization carried out by European kingdoms since the end of the 15th century. That said, decolonial feminism is above all groups of colonized, racialized, racialized women in collective struggles against the multiple violences of the patriarchal colonial system (Espinosa-Miñoso et al., 2022). It is a movement rooted in the experiences of indigenous and Afro-descendant women in Abya Yala, from the south, the center and the Caribbean region. The intensification of their demands marks a milestone in 1992, five hundred years after the “Discovery”, this papal doctrine now rejected. Decolonial feminism is at once autonomous, communal, critical and political; “it reveals the limits of the mainstream feminist approach, but also the virtual absence of criticism of patriarchy in the problematization of the coloniality of power” (Bourguignon, 2021, section 45).

While addressing the specific question of gender, decolonial feminism embraces questions of power as a whole, notably, the racial and colonial questions that form the fabric of relations in the City (Polis), in other words, the very idea of politics. Françoise Vergès (2019, pp. 19, 20) describes the movement of “feminisms of decolonial politics” as a milestone in decolonization that has helped racialized women assert their “right to exist.” This right, which is denied and undermined within democracies themselves, requires questioning democracies in their particularities and, above all, democracy in its essence. Subservient to racism-ethnicism, patriarchy-machismo, capitalism-classism, and extractivism-developmentalism, democracy cannot claim to be the political system of/by/for all. In this eco-geopolitical era of the Colonialocene, democracy is trapped, a victim of coloniality; and with it, women and the Earth are also victims of coloniality.

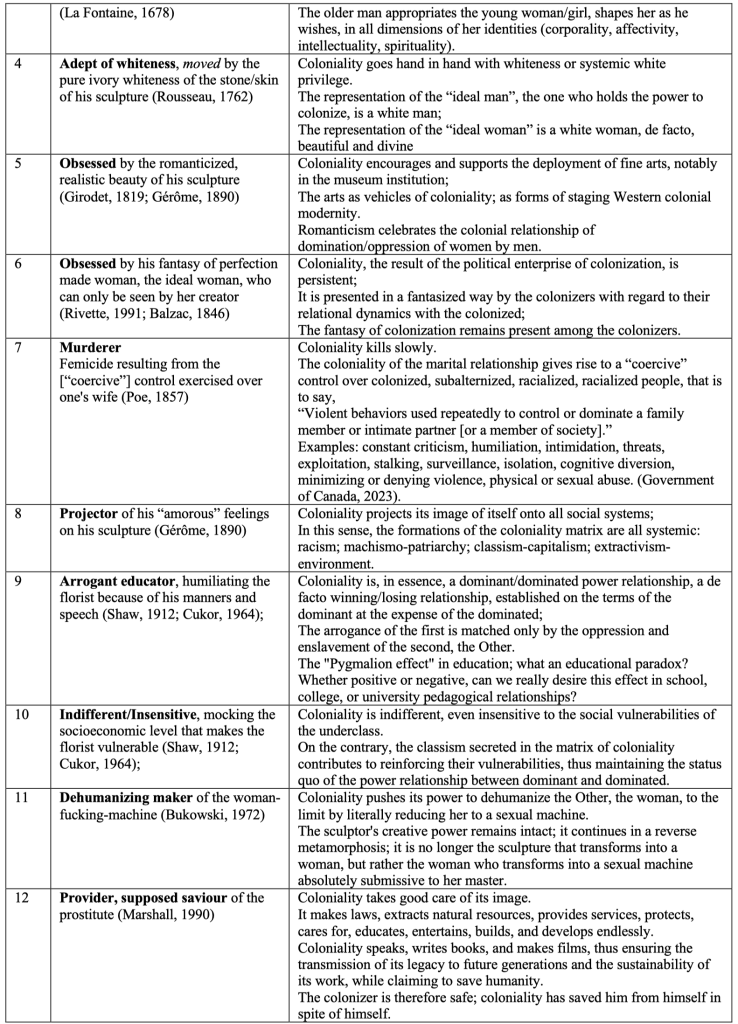

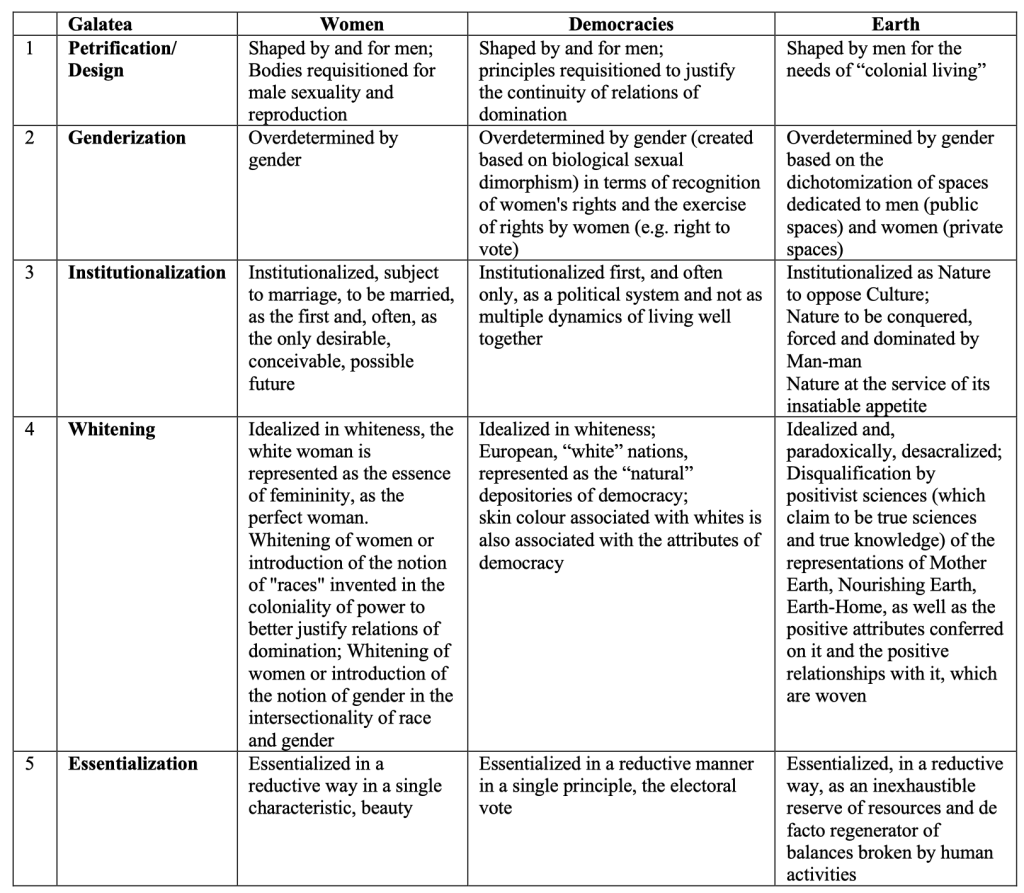

In the following table 2.2, I establish some similarities between Galatea’s situation and the situations of women, democracies, and the Earth.

The revenge of Galatea-Women/Democracies/Earth on Pygmalion-Coloniality

Like Galatea, sculpted and made into a statue by Pygmalion, women, democracies, and the Earth are also sculpted, petrified, and made into a statue in coloniality. They suffer the same colonial oppressions and must wage the same decolonial struggles. Decolonial feminism reveals itself as true humanism. It is inspired, first and foremost, by the feminists of the South and the center of Abya Yala (Espinoza-Miñoso et al., 2022). That said, thinkers from diverse geopolitical and cultural contexts have contributed to it; I highlight the following feminists:

- African-American lawyer Kimberlé Crenshaw (1991);

- American anti-racist and feminist philosopher and historian Angela Davis (2016, 2006);

- Brazilian intellectual and activist Lélia Gonzalez, 2024;

- African-American feminist critical pedagogue bell hooks (2014);

- Argentinian decolonial feminist philosopher Maria Lugones (2019);

- Indian ecofeminist environmentalist Vandana Shiva (2005);

- French-Reunion Island historian and political scientist Françoise Vergès (2019);

- the American-Ecuadorian decolonial pedagogue Catherine Walsh (2015);

- and first and foremost, feminist decolonial feminism reveals itself to be a true humanism.

On the one hand, decolonial feminism is expressed concretely in various feminisms of decolonial politics, and on the other hand, it offers levers that raise/elevate the quest for justice for women, which means justice (racial, social, environmental) for all (Vergès, 2019; hooks, 2014; Davis, 2006). In this sense, to serve the cause of justice for all, democracy trapped in coloniality has every interest in using the levers of decolonial feminism “as a utopian imaginary,” and also, as critical pedagogy and as collective practices of narratives that invite emancipation, indocility, and resistance while daring resilience and connection (Thésée, 2006; Morin, 2001). We must “unravel our concepts of capitalism and democracy […] invent new variants of democracy.” (Davis, 2006, p. 24), Earth-Democracies.

To this end, Galatea’s followers, women, democracies, and the Earth, and Galatea herself, should equip themselves with an imperative for revenge. Revenge is not vengeance; while the latter aims at the destruction of the other person, the former simply aims at self-affirmation. Revenge is an appropriate response to a situation of chronic injustice in order to restore balance and repair the harm suffered. Certainly, it requires willpower, courage, and perseverance, but also wisdom, serenity, and even radical human love. Revenge can be seen as a sine qua non for collective transformation, individual emancipation, and resilience. There is hope! Aragon (2024) announces the inversion, or even the end, of the myth of Pygmalion as Galatea finally speaks!

For her revenge on Pygmalion-Coloniality, Galatea-Women/Democracies/Earth sets out on the path, marches for her “real metamorphosis”, the one that leads her towards her emancipation by undoing the states of petrification and the situations of oppression that she has suffered for twenty centuries in the multiple representations of her. Galatea’s revenge could consist of a set of twelve labours, not as a punishment[9], but rather in response to each of the twelve representations of her, which are as many acts of violence inflicted on her. In this sense, in reference to the representations of the previous section, Galatea’s twelve labours of emancipation are presented as follows:

- To free herself from the stone shell that petrifies her, immobilizes her, reduces her to silence and submission, preventing her from being fully herself; to dare to be herself!

- Deconstruct the normative overdetermination of gender, which annihilates it in a supposed “perfection made woman”; reconstruct its plural identities in the fluidity of the human gender;

- Reject the precepts of heterosexual marriage, which are based on the legal, civil, political, social, educational, economic, etc., infantilization of women; reinvent the institution of marriage for the development of women and men, and for better harmony between them;

- Become aware of the excesses and consequences of representations of white skin associated with purity, perfection and divinity; connect, in plural solidarity with women of the world, in the diversity of their skin colours and other phenotypic characteristics;

- Resist the injunction of hegemonic “idealized beauty” and the false character of romance; open up to the beauty of human diversity in its various bodily variations, co-construct healthy, harmonious female-male relationships;

- Celebrate one’s authentic being in the world and one’s unique presence in the world by denouncing objectification/reification, exercising one’s being in the world;

- To flee at all costs the “coercive control” of oneself exercised by the “loving husband” which ultimately leads to the death of oneself; to regain one’s freedom, not to sacrifice it again;

- Avoid being defined by the romantic feelings projected onto you; reclaim your own romantic feelings;

- Criticize the self-image in the distorting social mirror held up to women and with which their humiliation, alienation, domination, and oppression are carried out;

- Healing the wounds inflicted on women’s identities, citizenships and globalities; struggling against social injustice and the impoverishment of women orchestrated by society and from which their multiple vulnerabilities arise;

- Proclaim the basic principle of human dignity for all, always, against all odds… while denouncing the dynamics of dehumanization of women;

- To unmask the “sexual service” and the power relations induced by this “win-lose transactional situation” presented in the romanticized film Pretty Woman; to awaken to the inherent violence suffered by women in this situation of sexual coercion.

As presented, this list does not capture the complexity, circularity, and interrelated nature of Galatea’s twelve emancipatory labours. Galatea’s revenge on Pygmalion, and by extension, the revenge of women, democracies, and the Earth on Coloniality, must be done holistically. In other words, it involves the entire being. Galatea’s twelve emancipatory labours mobilize the entire being in these four fundamental dimensions and fundamental elements: its corporeality (body/Earth); its affectivity (emotions/Water); its intellectuality (thoughts/Air); its spirituality (sense of being-in-the-world/Fire). The four symbolic elements (Earth, Water, Air, Fire) associated with the twelve dimensions are inspired by the Earth itself. Below, I present the twelve labours by associating them with the four universal elements.

- Earth Element: Shed the stone shell that petrifies it, immobilizes it, reduces it to silence and submission; Deconstruct the normative overdetermination of gender that annihilates it in a supposed “perfection made woman”; Resist the injunction of hegemonic “idealized beauty”.

- Water Element: Refuse the precepts of heterosexual marriage, which are based on the legal, civil, political, social, educational, economic, etc., infantilization of women; Flee at all costs the “coercive control” of oneself exercised by the “loving husband”; Avoid being defined by the loving feelings projected onto oneself;

- Air Element: Become aware of the excesses and consequences of the representation of the whiteness of one’s “stone skin”; Criticize self-image in the distorting social mirror held up to women; unmasking “sexual service” as well as the power relations induced by this “win-lose transactional situation”;

- Fire Element: Celebrate in Joy one’s authentic being in the world and one’s unique presence in the world by denouncing objectification/reification; Heal the wounds inflicted on women’s identities, citizenships and globalities by fighting against social injustice and impoverishment from which their multiple vulnerabilities arise; Proclaim the basic principle of the human dignity of all, always, against all odds… while denouncing the dynamics of dehumanization of all.

I bet that these twelve emancipatory works of Galatea, categorized according to the four symbolic and universal elements, apply in an interrelated way: to women, with a more sociological scope; to democracies, with a more political scope; and to the Earth, with a more ecological scope. Each of the twelve works invites a reflective dialogue where we explore in depth the symbolism of the universal element, then the meaning of the underlined verb and then the description of the object relative to the verb. The reflective dialogue is done collectively based on values of listening, openness and learning through sharing knowledge. The discussion on the symbolism of the elements, the meaning of the underlined verbs and the description of the object is done according to a dialectic where, between theses and antitheses, the paths of thought move towards a common synthesis, although this may be of a teleological nature, that is to say, of the order of the democratic ends towards which societies should tend. That said, can democracy engage in decolonial transmodernity (Dussel, 2012) or take the decolonial turn (Maldonado-Torres, 2008), or even choose the decolonial option (Walter Mignolo, 2007)?

Conclusion

This chapter, Galatea’s Revenge on Pygmalion. Women, Democracies and Earth: Same Colonial Oppressions, Same Decolonial Struggles! is part of the present book entitled Pygmalion Democracy. If you build it, will they come?

At the very beginning, I had wanted to show how the “Pygmalion Effect” (or Rosenthal and Jacobson effect in psychology) was described as “self-fulfilling prophecies”, positive or negative, between a teacher and his student (Trouilloud & Sarrazin, 2003), could apply as well to the “student democracy” facing his “teacher Pygmalion”. However, over the course of my readings, re-readings and analyses of the “Myth of Pygmalion”, by various authors, in various Western cultural contexts, in various artistic disciplines, at different times and from various angles, I realized that the sculptor Pygmalion was becoming more and more in the background and that the center of the myth was gradually occupied by his statue, later named, Galatea. Moreover, this myth seemed to me to resonate more and more with the biblical story of the Garden of Eden where, through divine intercession, Eve was supposedly created from Adam’s rib and later became the one through whom Adam sinned. From then on, my attention was mainly focused on the being of Galatea, her birth, her life situation, her multiple experiences as an artistic figure, her social development, and her inexorable destiny. This is why, in this chapter, it is Galatea that is discussed not as a character, but now as a person. Galatea takes her revenge on Pygmalion by creating her own myth, “the myth of Galatea,” based on her twelve labours of emancipation and by joining all oppressed people in plural solidarity. I therefore propose to approach democracy through the person of Galatea, while recognizing that she was and still is shaped, petrified, sculpted by Pygmalion. Galatea-Women, Galatea-Democracies or Galatea-Earth, these are the same colonial oppressions experienced; they are therefore the same decolonial struggles to be carried out together.

In the first section of the text, I set out the context in which my reflection is situated, namely the eco-geopolitical era of the Colonialocene, which I described by drawing on ten neologisms that have emerged since the beginning of the 21st century. In the second section, I outlined the contours of the colonial democracy(ies) shaped in the context of the Colonialocene. In the third section, I presented the “Myth of Pygmalion” through some of its artistic adaptations in the West, the most well-known over the centuries. It is the critical analysis of these works that gradually led me to shift my attention from Pygmalion to Galatea, from masculine to feminine, from oppressor to oppressed. In the fourth section, I revisit the myth of Pygmalion, renaming it “Pygmalion-Coloniality” and highlighting its features, which constitute the violence inflicted on Galatea. In the fifth section, I developed a theoretical framework inspired by decolonial feminism, which allowed me to name and describe twelve situations of oppression experienced by Galatea. In the sixth and final section, I constructed what I call “Galatea’s twelve labours of emancipation,” which I hope can find concrete applications in the decolonial struggles of women, democracies, and the Earth.

“Revenge” is not “revenge”; I insist on this distinction because the two concepts are often confused and used as synonyms. However, the difference between these two concepts concerns a primary principle of decoloniality, relating to otherness, namely pacifism, the absolute quest for “Peace” and “radical human Love”. Galatea’s revenge is part of the decolonial struggles already underway, for several centuries, notably, the struggles of women in the Global South that they wage tirelessly against colonial domination and oppression. Galatea’s revenge is nourished by the knowledge co-constructed by these women in sociological dimensions: ethical, political, critical and aesthetic; as well as in epistemological dimensions: ontological, axiological, methodological and praxeological.

Over the centuries, the myth of Pygmalion has been the subject of numerous adaptations or reinterpretations in key works of classical and popular Western art. What is the significance of the pervasiveness of this myth in culture? What are the impacts of the representations of the feminine and the masculine that are conveyed? What are the consequences of these representations in the social relationships of women and men? And above all, how do these conveyed representations crystallize in women and men, and in their relationships? Authors from different disciplinary fields revisit the myth (Mijolla-Mellor, 2008; Chen, 2006). They invite us to go beyond the falsely playful, entertaining, aesthetic or romantic character of this myth, to become aware of the relationship of total domination of the female character by the male character. In these times when we are observing the emergence of a worrying masculinist movement that threatens women (Dupuis-Déri, 2009) and when a crisis of masculinity is raging (Dupuis-Déri, 2018), other critical analyses allowing us to understand the profound effects of the Pygmalion myth are necessary.

Regarding the central theme of the book, that of democracy, I hope this chapter sheds new light. Associated with Galatea, a sculpture of Pygmalion and victim of the dynamics of domination and oppression of the male archetype over the female archetype, feminized democracy takes on new faces, the faces of women and the faces of the Earth (Mother Earth; Pacha-Mama; Gaia). Democracy is endowed with the power to decolonize itself and is entrusted with the realization of Galatea’s twelve labours of emancipation. In doing so, democracy is no longer taken for granted as it has been and still is petrified, sculpted, objectified, and put at the service of coloniality. The relationship to democracy must be transformed into a commitment to “making democracy together.” Galatea-democracy can then be approached by oppressed people as an ally, an accomplice, a sister in decolonial struggles with them on the path to Justice (social, racial, environmental) and Peace, in order to build together democracies that truly want to live well together on Earth or Buen Vivir (Sauvé, 2009; Morin, 2001).

I am aware that I have left a fourth war in the blind spot of the chapter, namely the war specifically waged against people of African descent in Abya Yala, in other words, the endless war against Black people (Maldonado-Torres, 2016). I have deliberately not made it explicit here, considering that the crucible of coloniality includes anti-Black racism and that decolonial struggles include the struggles of Black people against racism(s) and colonialisms (Casimir, 2020). That said, the scale, severity, and acute consequences of this fourth war, transmitted to the descendants of enslaved people from generation to generation, require that it be given due attention. Moreover, this text certainly has limitations. This is the result of my perspective on “the myth of Pygmalion” in light of my readings, re-readings, and analyses informed by the many authors who inspired me throughout the writing of this text. I recognize that my perspective is not free from biases that are inherent to my epistemo-political stance as a decolonial feminist. I am therefore not neutral, which I ardently claim and fully assume.

References

Aragon, S. (2024). Le mythe de Pygmalion s’inverse, Galatée prend enfin la parole. Slate. https://www.slate.fr/story/266006/cinema-litterature-fin-mythe-de-pygmalion-galatee-metoo

Armiero, M. (2024). Poubellocène. Chroniques de l’ère des déchets. Lux Éditeur.

Berthier, M. & Boutard, A. (2016). Mythe de Pygmalion. La relation de l’artiste à son œuvre la femme-objet. Université Lumière. https://www.molon.fr/EITL/metamorphoses/Telechargements/EITL-Metamorphoses-Pygmalion.pdf

Bonneuil, Ch. & Fressoz, J.-B. (2013). L’Evènement Anthropocène, la Terre, l’histoire et nous. Le Seuil.

Bourbon, M.-C. (2024). Sommes-nous vraiment entrés dans l’Anthropocène? La désignation d’un lac ontarien comme témoin de la nouvelle époque géologique a relancé le débat scientifique. Actualités UQAM. https://actualites.uqam.ca/2023/sommes-nous-vraiment-entres-dans-lanthropocene/

Bourguignon Rougier, Cl. (2021). Un dictionnaire décolonial. Perspectives depuis Abya Yala. Afro Latino America. Éditions science et bien commun.

Campagne, A.(2017). Le capitalocène: aux racines historiques du dérèglement climatique. Éditions Divergences.

Caparros, D. (2024). Le mythe de Pygmalion au cinéma : vers une émancipation du regard masculin. Radio-France. Publié le vendredi 15 mars 2024 à 17h19. https://www.radiofrance.fr/franceculture/le-mythe-de-pygmalion-au-cinema-vers-une-emancipation-du-regard-masculin-5118033

Carrière, J.-C. (2021). À la vie! Odile Jacob.

Casimir, J. (2020). The Haitians: A Decolonial History (L. Dubois, Trans.). University of North Carolina Press.

Chen, L. (2006). A Feminist Perspective to Pygmalion UNE PERSPECTIVE FÉMINISTE SUR PYGMALION. Canadian Social Science, 2(2), 41–44. http://www.cscanada.net/index.php/css/article/viewFile/j.css.1923669720060202.008/258

Clark, J. P. (2019). From the Necrocene to the Belobed Community. PM Press.

Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241–1299. https://doi.org/10.2307/1229039

Davis, Angela Y. (2006). Les goulags de la démocratie. Réflexions et entretiens. Écosociété.

Davis, Angela Y. (2016). Sur la liberté. Petite anthologie de l’émancipation. Éditions Aden.

Dupuis-Déri, F. (2009). Le « masculinisme » : une histoire politique du mot (en anglais et en français) “Masculinism” : A Political History of the Term (in English and French). Recherches féministes, 22(2), 93-123. https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/039213ar

Dupuis-Déri, F. (2018). La crise de la masculinité. Autopsie d’un mythe tenace. Remue-Ménage.

Dussel, E. (2002). Democracy in the “Center” and Global Democratic Critique. In O. Enwezor, C. Basualdo, U. M. Bauer, S. Ghez, S. Maharaj, M. Nash & O. Zaya (eds.) Democracy Unrealized. Hatje Cantz Publishers.

Dussel, E. (2012). Transmodernity and Interculturality: An Interpretation from the Perspective of Philosophy of Liberation. TRANSMODERNITY: Journal of Peripheral Cultural Production of the Luso-Hispanic World, 1(3), 28-59.

Espinosa-Miñoso, Y., Lugones, M., & Maldonado-Torres, N. (Eds.). (2022). Decolonial feminism in Abya Yala: Caribbean, meso, and South American contributions and challenges. Bloomsbury Academic.

Falquet, J. (2021). Généalogies du féminisme décolonial. En femmage à María Lugones. Cairn Info. Sciences humaines et & sociales, 84, 68-77. https://shs.cairn.info/revue-multitudes-2021-3-page-68?lang=fr

Fanon, Frantz (1970). Les damnés de la terre. Maspero.

Ferdinand, M. (2019). Une écologie décoloniale. Penser l’écologie depuis le monde caribéen. Éditions du Seuil.

Gauchet, M. (2008). Crise dans la démocratie. La revue lacanienne, 2(2), 59-72. https://shs.cairn.info/revue-la-revue-lacanienne-2008-2-page-59?lang=fr

Gonzalez, L. (2024). Por un Feminismo afro-latino-americano. https://negrasoulblog.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/lc3a9lia-gonzales-carlos-hasenbalg-lugar-de-negro1.pdf

Gouvernement du Canada. Ministère de la Justice (2023). Contrôle coercitif. https://www.justice.gc.ca/fra/pr-rp/jr/reb-rib/capcvf-mpafvc/pdf/RSD_2023_MakingAppropriatebrochure-fra.pdf

Gibbard, P. L. & Walker, M. J. C. (2013). The term ‘Anthropocene’ in the context of formal geological Classification. Geological Society London Special Publications, 395, 29–37.

hooks, bell (2014). Yearning: Race, Gender, and Cultural Politics, Routledge.

Latour, B. (1996). Petite Réflexion sur le culte moderne des dieux faitiches. Les Empêcheurs de penser en rond. https://shs.cairn.info/sur-le-culte-des-dieux-faitiches–9782359250046-page-7?lang=fr

Lesec, C. (2008). Pygmalion ou le pouvoir du mythe. Perspective. Actualité en histoire de l’art, 2, 337-342.

Louvre (Musée du) Collections (2019). Pygmalion et Galatée. Tableau acquis en 2002. https://collections.louvre.fr/ark:/53355/cl010067324

Lugones, María (2019). La colonialité du genre. Les cahiers du CEDREF, No. 23, p. 46-89. https://journals.openedition.org/cedref/1196

Maldonado-Torres, N. (2008). La descolonización y el Giro descolonial. Tabula Rasa, No.9, p. 61-72.

Maldonado-Torres, N. (2016). Outline of Ten Theses on Coloniality and Decoloniality*. Fondation Frantz Fanon.

Maldonado-Torres, N. (2023). Analytique de la colonialité et de la décolonialité. L. Álvarez Villarreal et M. Maesschalck (éd.) Pluraliser les lieux. EuroPhilosophie Éditions. https://doi.org/10.4000/books.europhilosophie.1636

Marshall, G. (Director). (1990). Pretty Woman [Film]. Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures.

Mediterranées. Site (sans date). Jean-Jacques Rousseau – Pygmalion (1762-1770) https://mediterranees.net/mythes/pygmalion/rousseau.html

Memmi, Albert (2003). Portrait du colonisé. Précédé du portrait du colonisateur. Gallimard.

Mijolla-Mellor (de), S. (2008). Le fantasme de Pygmalion. Adolescence, 26(4), 817-840. https://shs.cairn.info/revue-adolescence-2008-4-page-817?lang=fr

Mignolo, Walter D. (2007). La idea de América latina. La herida colonial y la opción decolonial. Gedisa Editorial.

Moore, J. W. (2017). The Capitalocene, Part I: on the nature and origins of our ecological crisis. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 44(3), 594–630. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2016.1235036

Morin, E. (2001). Reliances. L’Aube.

Natural History Museum, & Pavid, K. (n.d.). What is the Anthropocene and why does it matter? Nhm.ac.uk. https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/what-is-the-anthropocene.html

Niebuhr, R. (1986). The Essential Reinhold Niebuhr: Selected Essays and Addresses. Yale University Press.

Quijano, A. (2007). « Race » et colonialité du pouvoir. Mouvements, 51, 111-118.

Quijano, A. (2000). Colonialité du pouvoir, eurocentrisme et Amérique latine.

Quijano, A. (1992). Colonialidad y Modernadidad / Racionalidad. Perú Indig, 13(29), 11-20.

Ruault, L., Hertz, E., Debergh, M., Martin, H., & Bachmann, L. (2021). Androcène (2021/22 ed., Vol. 40). Nouvelles Questions Féministes. https://shs.cairn.info/revue-nouvelles-questions-feministes-2021-2?lang=fr

Rivette, J. (Director). (1991). La Belle Noiseuse [Film]. Pierre Grise Distribution.

San Román, Á., & Molinero-Gerbeau, Y. (2023). Anthropocene, capitalocene or westernocene? On the ideological foundations of the current climate crisis. Capitalism Nature Socialism, 34(4), 39–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/10455752.2023.2189131

Sarr, Felwine (2013). Habiter le monde. Essai de politique relationnelle. Mémoire d’encrier.

Sauvé, L. (2009). Vivre ensemble, sur Terre : enjeux contemporains d’une éducation relative à l’environnement. Éducation et francophonie, 37(2), 1-10. https://doi.org/10.7202/038812ar

Seyrig, D. (1971). Radioscopie (Cinéma): Jacques Chancel reçoit Delphine Seyrig. Radio-France. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kkn8cpS4uw0&list=OLAK5uy_k_56wIksBiE8D2x38oBjs5gUwMYvayD9c&index=2

Shiva, V. (2005). Earth Democracy: Justice, Sustainability and Peace. Cambridge: South End Press.

Tamés, R. (2022). Les droits des femmes, boussole pour la démocratie. Regina. https://www.hrw.org/fr/news/2022/11/25/les-droits-des-femmes-boussole-pour-la-democratie

Taubira, C. (2017). Nous habitons la terre. Éditions Philippe Rey.

Théâtre du Rideau vert. (1999). Pygmalion. Du 28 septembre au 23 octobre 1999. Traduction : Antonine Maillet. Mise en scène : Françoise Faucher. Revue Théâtre. Volume 51, No 2, saison 1999-2000. https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/3260105

Thésée, G. (2006). A tool of massive erosion: Scientific knowledge in the neo-colonial enterprise. In G. J. Sefa Dei & A. Kemp (Eds.), Anti-Colonialism and Education: the Politics of Resistance (pp. 25–42). Brill.

Trouilloud, D., & Sarrazin, P. (2003). Note des synthèse [les connaissances actuelles sur l’effet pygmalion : Processus, poids et modulateurs]. Revue Française de Pédagogie, 145(1), 89–119. https://doi.org/10.3406/rfp.2003.2988

UIP (2021). La démocratie triomphe, une fois encore. Union parlementaire. Pour la démocratie. Pour tous. https://www.ipu.org/fr/actualites/opinions/2021-02/la-democratie-triomphe-une-fois-encore

UNESCO (1996). L’éducation, un trésor est caché dedans. UNESCO.

Vergès, Fr. (2019). Un féminisme décolonial. La Fabrique éditions.

Walsh, C. E. (2015). Decolonial pedagogies walking and asking. Notes to Paulo Freire from AbyaYala. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 34(1), 9–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/02601370.2014.991522

Wolford, W. (2021). The Plantationocene: A Lusotropical Contribution to the Theory. Annals of the American Association of Geographers. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2020.1850231

- “Man's capacity for justice makes democracy possible, but man's inclination to injustice makes democracy necessary.” (Reinhold Niebuhr, 1986). ↵

- Abya Yala: “Abya Yala means 'Land of life,' 'land of full maturity,' 'land of blood'.” Latin American indigenous organizations decided, on the 500th anniversary of the “Discovery,” to no longer use the term “America.” They see it as a trace of the European, more precisely Italian, ego, the shadow of Amerigo Vespucci. They therefore adopted the word kuna to designate the continent.” (Bourguignon Rougier, 2021; Dictionnaire décolonial, section 1). ↵

- NHM: Natural History Museum of London. ↵

- “Manman” is the Creole term for mother; a “land without manman” is a land without mother. ↵

- Inter-Parliamentary Union. For democracy. For all.; https://www.ipu.org/en ↵

- Referring to the Greek term "nomos", the etymological root of heteronomy and autonomy. ↵

- According to the website of "Once Upon a Time at the Cinema" (undated). "The Beautiful Noiseuse". ↵

- Note that "Histoire d'O" caused a scandal and that "Lolita" was withdrawn from sale in France twice (Mijolla-Mellor, 2008, p. 817). ↵

- In reference to the myth of Hercules and his twelve labors. ↵